The first two sentences of Hurricane Season are deceptively short, simple even. Here is the third:

The rest of the troop trailed behind him in their underwear, all four caked in mud up the their shins, all four taking turns to carry the pail of small rocks they’d taken from the river that morning; all four scowling and fierce and so ready to give themselves up for the cause that not even the youngest, bringing up the rear, would have dared admit he was scared, the elastic of his slingshot pulled taut in his hands, the rock snug in the leather pad, primed to strike at anything that got in his way at the very first sign of an ambush, be that the caw of the bienteveo, perched unseen like a guard in the trees behind them, the rustle of leaves being thrashed aside, or the whoosh of a rock cleaving the air just beyond their noses, the breeze warm and the almost white sky thick with ethereal birds of prey and a terrible smell that hit them harder than a fistful of sand in the face, a stench that made them want to hawk it up before it reached their guts, that made them want to stop and turn around.

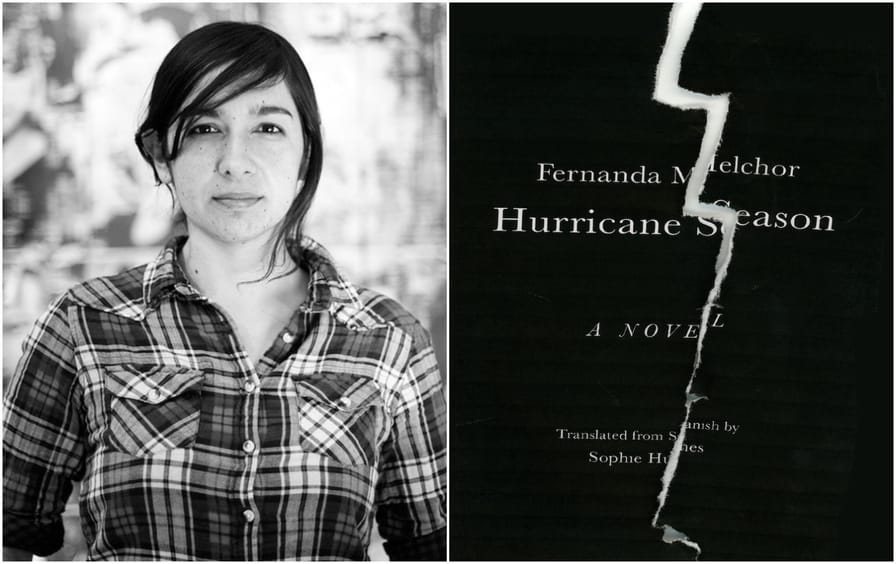

That, in a nutshell, is the experience of reading Hurricane Season, a novel that sweeps you away in a torrent of overwhelming, recursive, brutal language, sometimes forward, sometimes in circles, but always in motion.

I have a special place in my heart for novels that try to dictate the reading experience itself. It’s as if it wasn’t enough for the author to simply invite you into their head for a few hundred pages: they also want to sit on your shoulder, demanding that you read faster or slower, that you flip ahead to the end or learn a second language on the side. Mark Danielewski’s House of Leaves accomplishes this by spacing out the text so that only a few words are left on each page; the effect is an unexpected mad sprint to the end of the novel. David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest keeps you flipping to the end of the novel to consult the footnotes, which might contain a brief aside or an entire chapter. Hurricane Season resembles some works of the modernist masters, Faulkner and Joyce, by its refusal to end its sentences in a timely manner. As a reader, there’s no good way to put it down, no stopping point. Melchor compells you to keep reading.

The justification for this style of narrative is that the author has tapped the reader directly into the brain of the protagonist(s). Human thought is messy, it doesn’t follow grammatical conventions. This also helps to explain the recursive nature of the narrative: there are some things we can’t stop thinking about, ideas and events that the novel returns to over and over again.

It’s important that Melchor’s prose propels the reader through Hurricane Season because the story itself, which layers horror upon horror, makes you want to stop1. Its themes are violence and trauma and anger and survival, the tale of a society rotting from the inside out. Melchor has been compared to Roberto Bolaño, but she tackles violence rather differently. Rather than letting the bodies pile up, their killers just offstage, as Bolaño does in the grisly fourth section of 2666, Melchor gives us a corpse in a canal and lets the novel unfold around the story of this singular murder victim and her murderers.

The four chapters that make up the core of the novel explore the crime from the perspectives of four individuals, Rashomon-style, each one unreliable and ultimately betrayed by their own thoughts. Each version of the mystery gives us a little more information, but Melchor cleverly plays upon our expectations to subvert and complicate her story. Without spoiling the twists of the novel, I’ll just say that everything that seems obvious and true about Hurricane Season early on is revealed as superficial or false by its end.

These new revelations are disorienting. With each new chapter the reader has to reorient themselves, to see what was previously trivial or incidental as of central importance. Melchor’s linguistic twists and turns build up energy and tension until we’re just where she wants us: deeply in each character’s head, fully invested in their story. One final twist and the tension is too great, everything snaps:

Grandma wheezed with the effort of staying alive, no longer capable of speech, only peeling her eyes from the ceiling for one terrifying moment, when Yesenia rested her grandmother’s head on her lap to caress the old girl’s coarse white hair, telling her that it was okay, everything was going to be okay, the doctor was on his way to make her better, she must hold on a little longer and be strong for her, for them, for her granddaughters who adored her, but the words stuck in her throat when the old woman dropped her gaze and locked eyes with Yesenia, and who knows how, who knows how Yesenia could tell, but she’d have sworn on the Holy Cross that Grandma looked at her as if she knew what she’d done, as if she could read her mind and knew that it was Yesenia who’d ratted out the kid, who told the police in Villa where the little shit lived so they could go and arrest him. And Yesenia also knew, as she drowned in the old woman’s furious eyes, that Grandma despised her with every ounce of her being and in that very moment she was putting a curse on Yesenia, and in the faintest of voices Yesenia begged for forgiveness and explained that it had all been for her, but it was too late: once again, Grandma hit Yesenia where it hurt most, dying right there, trembling with hate in the arms of her eldest granddaughter.

Intense as that passage may be, it’s actually pretty tame by the standards of the second half of the novel. Hurricane Season isn’t for everyone. If you’re the type of reader who doesn’t want to read descriptions of violence or sexual assault, I’d pick something else to read2.

From a technical point of view, Hurricane Season is basically perfect. I’ve rarely read a novel that so successfully accomplishes what it set out to do. The question is what to make of where Melchor leaves us at the novel’s end.

Here’s a passage from the devastating sixth chapter:

Because the truth was that his mother served literally no purpose: she didn’t work, she didn’t earn shit, she spent her life either in church or glued to the TV screen watching soap operas or reading celebrity magazines; her sole contribution to the world was the carbon dioxide she exhaled with each breath. An utterly pointless life, a dead loss. He’d be doing her a favor killing her—an act of compassion.

It’s a Dostoyevskyan moment, a repudiation of kinship and morality, a fever dream of murder reframed in a broken world as “an act of compassion.” And not just any murder: it’s the kind of killing born out of disgust and hatred, a private genocide carried out within the family unit.

One way to read Hurricane Season is to focus on the darkness, to read it as a Lord of the Flies style parable, an exploration of what it means to be human when we lose the trappings of family and security and comfort and empathy. That’s the message we get from the opening passage, with its troop of boys “caked in mud up the their shins,” who could have walked straight out of the pages of William Golding’s novel and into Melchor’s. This reading leaves us with a novel that is both brilliant but ultimately unsatisfying. There must be some point to all this pain.

Another reading acknowledges that Hurricane Season has glimmers of light as well—not many, but they exist. There are brief moments of hope from within the whirlwinds of evil that surround the protagonists, pieces of an odd and twisted love story amid the horror. It’s a testament to the power of Fernanda Melchor’s prose that she doesn’t overwrite these moments. To do so would leave an unpleasant saccharine taste that would clash with the tone of the rest of the novel. This is, I think, the reading that I favor, but it’s close: there’s so much suffering in this novel, and so few moments of hope.

Ultimately, this is a stunning work of literature. I’m not sure I ever want to read it again, but I am glad that I read it.

I took a week off between chapters four and five, not because I wasn’t engrossed in the story, but to give myself a break from the brutality of the world Melchor had created.

My only-reads-a-few-sight-words five year old leaned over my should while I was finishing Hurricane Season and I told her that she had to stop looking at the book—that’s the kind of effect it has. It’s definitely getting stashed on a high shelf away from everyone under five feet tall.