One of my favorite tournaments of the year, the U.S. Championship, starts this week. It wasn’t always this way: during my youth the U.S. Championship was a contest between the Americans of the Fischer generation and a group of Soviet expats. They were all capable grandmasters, but none were a threat to Kasparov’s iron grip on the world championship. As such, the U.S. Championship of the 1990s was Cold War melodrama. By comparison, today’s U.S. Championship is a major international event of sorts, pitting the best players from the United States against the top player produced by the Philippines, Armenia, and Cuba1, all united under the American flag. Winning this tournament means that you’re a real challenger for the world championship; American chess is no longer overshadowed by the Soviet system.

But that’s not why I love the U.S. Championship. I love it because I got to play some of America’s top grandmasters when they were kids. I got to play them early enough that I won some games before they surpassed me thanks to their talent and dedication, and now I get to root for them as they battle some of the best players in the world. This year’s event includes three former Bay Area kids: Sam Shankland, Sam Sevian, and Hans Niemann.

The Technician: Sam Shankland

I’ve known Sam Shankland the longest of the three. We met in 2004 when I started giving him weekly lessons. Sam was, as far as anyone could tell at the time, just another reasonably talented thirteen year-old, rated around 1600 and itching to shoot up to expert or master. If you told me back then that he would make FM or IM at some point I wouldn’t have been surprised, but as I’d never met anyone who’d crossed 2700 FIDE, the thought that he would become a super-GM never crossed my mind.

In those early days Sam was easy to beat. He played dodgy openings that didn’t suit his style and he didn’t yet have the confidence that he could take down higher rated players. That all changed as his rating grew quickly to 1900 and then 2000:

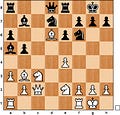

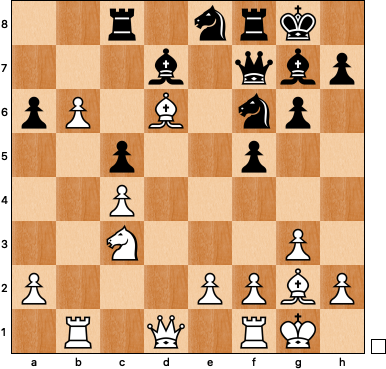

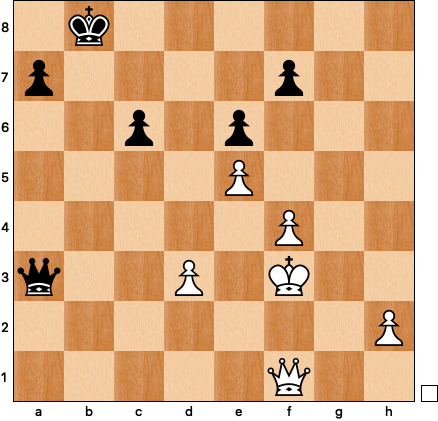

In this position from our third meeting I played the cavalier 15 h3? and Sam seized the initiative (and a big advantage) with a series of logical moves: 15 … Rc8 16 Ng3 Nc5 17 Bxc5 Rxc5 18 Rac1 Qc7 19 Rfe1 Rc8 20 Re3 Bb6:

White’s position is quite bad. The a7-g1 diagonal is going to be a problem, as is the threat of a5 and b4, winning the pinned Nc3. I struggled on for a while, but Sam finished me off without much trouble.

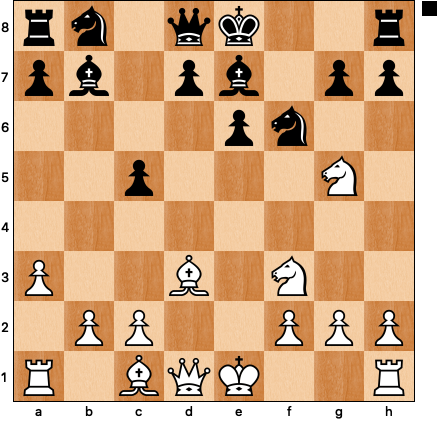

It’s hard to play against one’s former students2, but I played some interesting games against Sam in the years that followed, as he made master and then IM. The following year he tried out the Leningrad Dutch, and for a short while I had him on the ropes:

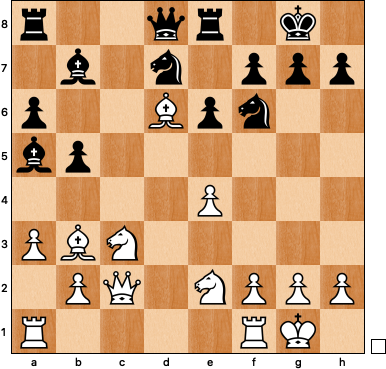

Black’s last move was a7-a6, taking advantage of the fact that white’s b5-b6 drops the knight. Something like 15 a4 would keep a significant advantage, but I rarely have to be asked twice to play a move that looks like a knockout blow. Therefore, I chose 15 Nxe7+!? Qxe7 16 Bf4 Rc8 (there’s no good way to defend d6) 17 Bxd6 Qf7 18 b6 Nce8:

In search of a forced win I blundered with 19 Be5? which allows the simplifying move 19 … Ne4! Sam eventually ground me down in an ending with two bishops against a rook; the game could have turned out differently if I’d been satisfied with 19 Bxf8! Bxf8 20 b7 Rb8 21 Rb6 when white is close to winning.

The last time we played at slow time controls was in 2010. I sacrificed an exchange on the black side of a King’s Indian Defense and Sam, despite suffering for a while on the wrong side of the initiative, once again came out on top. These contests reveal Sam’s strengths: he has excellent positional intuition and rarely beats himself by getting his pieces tangled or pushing too hard for a win. He takes what you give him and then goes to work, often making difficult technical positions look simple. If he wins some early endgame grinds in the 2024 championship, he could be as hard to stop as he was in 2018, the year he won it all3.

The Theoretician: Sam Sevian

Before moving to the east coast, Sam Sevian was a regular at weekend tournaments in the Bay Area. We first played when he was nine years-old and rated 2100, a scary moment to face a rising prodigy. Fortunately, I had some experience, having played the two youngest masters of the 1990s, Vinay Bhat and Jordy Mont-Reynaud, back in my high school days.

Before I sat down across from young Sevian for the first time, the legendary coach and local master Michael Aigner leaned over to me and whispered “this kid is booked up!” I decided to play 1 e4 in spite of his warning, and managed to steer an anti-Marshall into the following promising ending.

They say that the best way to beat kids is in the endgame, where adult experience rules over tactical imagination. In this game the aphorism proved true, as Sevian reacted passively and let me improve my position at no cost: 27 … Kh7 28 h4 Re7 29 h5 Re8 30 Kf1 Re7 31 Ke2 and only now, much too late, did he try to break free of the bind with 31 … g6, before white’s creeping movement of Ke3, f4, Ke4, and f5 left him totally helpless. I won the game without much difficulty.

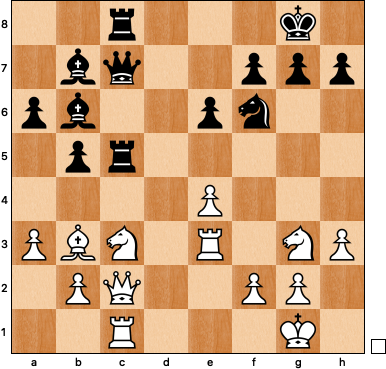

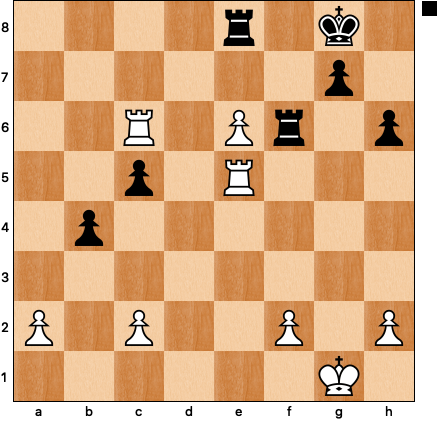

Fast forward two years, and Sevian had learned how to defend these kinds of positions:

This is the sort of tiny advantage that I might have nursed to victory against a weaker player, but my hopes were dashed when Sevian played 38 … g5!, planning to lock up the kingside before activating his rook on the only open file. I tried to reopen the position, but after 39 f4 gxf4 40 Rh5 Rd8! (to meet 41 Rxh6 with 41 … Rg8) 41 Ke2 (heading for f3, but conceding the c-file) 41 … Rc8 42 Kf3 Rc3+ 43 Kxf4 Rxa3 44 Rxh6 a5, black was out of danger4.

Sam Sevian has played the sharpest openings against me of the three. In our second meeting he played the Botvinnik Semi-Slav with the black pieces, a mind-bogglingly difficult line. His command of theory is rooted in strong understanding of opening strategy; Sam Shankland has said that Sevian is the best at figuring out good openings in Chess960. And in our last meeting, Sevian led me into a very difficult theoretical variation that I couldn’t quite extricate myself from, despite decades of experience on the black side of the French:

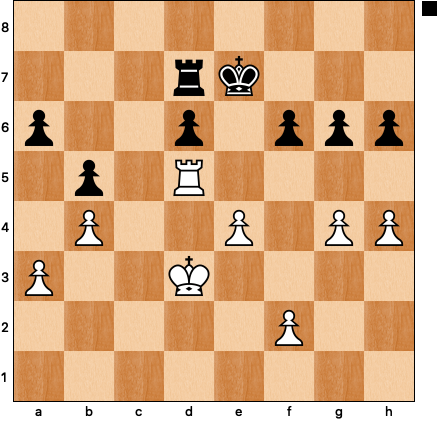

In this razor sharp variation of the Winawer Poison Pawn, Sevian played 22 Rxc6!? bxc6 23 Qc5. Fortunately, I was as booked up as he was, and quickly played the most straight-forward equalizer: 23 … Rxd3! 24 cxd3 Rxg2, and after 25 Rxg2 Qxg2 26 Qf2 Qd5 I was feeling pretty good about my position. In exchange for the pawn, black has the superior pieces and less exposed king. It’s hard to suggest a good way forward for white. Sevian played 27 Qf1 to defend d3, and I decided to go after the a-pawn, a decision I would later regret: 27 … Nd4 28 Be3 Nc2+? (28 … Nf5 would have been better) 29 Kf2 Nxe3 30 Kxe3 Qc5+ 31 Kf3 Qxa3:

Material is finally equal, but the cost was a bit high. White’s h-pawn is more dangerous than black’s a-pawn, and after 32 h4 a5?! 33 h5 a4? 34 h6 white’s advantage was too much and I wasn’t able to hold the game.

I haven’t followed Sevian’s adult chess career as closely as Sam Shankland’s or Han Niemann’s, but this year’s U.S. Championship seems like an opportunity for him to prove that he’s ready to take the next step up and above 2700.

The Disrupter: Hans Niemann

When non-chess players find out that I play competitive chess, they often bring up “the cheating thing” as a shared point of reference, only to be surprised to learn that I’ve played Hans Niemann a number of times and have known him since he was a kid.

I’ve dubbed Hans “The Disrupter” in part because his behavior as a kid was, well, disruptive. He was a little terror running around hotel conference rooms in Bay Area tournaments, and I once had to take him aside and use teacher voice on him to get him to calm down. I still laugh when I think about John Donaldson, long-time director of the Mechanics’ Institute Chess Room, hustling Hans out of the TD office, sternly saying, “Hans, I have to work now!”

The other half of Hans’ disruptiveness involves what it’s like to face him over the board. More so than either of the Sams, I’ve always found Hans to be an uncomfortable matchup5. In our games he’s often picked offbeat opening variations (such as the Center Game and the English Defense — 1 … b6) and for whatever reason I find his moves hard to predict. Here’s an example where I found myself lost right out of the opening:

My last move was Ne4-g5, a disrespectful I’m-gonna-blow-you-off-the-board incursion into black’s territory. Hans’ response was a shocker: 11 … c4! 12 Bxc4 h6. The bishop has been deflected, so there’s no Bg6+ and the Ng5 lacks a good retreat square (13 Nh3 g5 is a problem). I doubled down on the “attack,” but after 13 Qd3? hxg5 14 Qg6+ Kf8 15 Nxg5 Qe8 white has nothing: a pessimist might be ready to resign already. After many mutual errors, I was lucky enough to hold a bad ending.

Like Sevian, Hans also relocated to the east coast, and our most recent meeting was at the Amateur Team East, just before the pandemic. My team had the misfortune of getting very slow service at a crowded Thai restaurant between rounds , and we arrived over half an hour late to the game. I struggled to play quickly enough to reach the following ending:

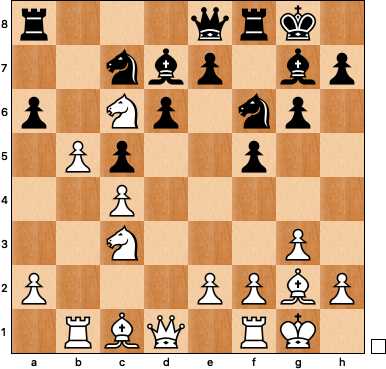

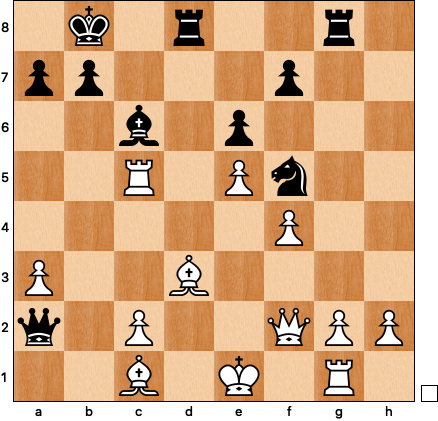

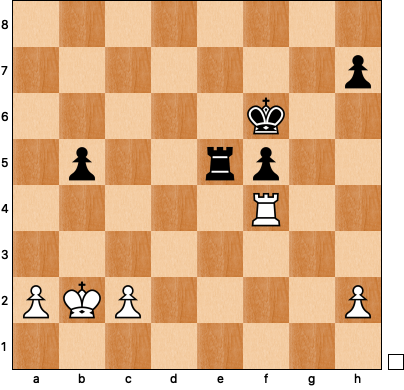

Hans’ last move was f7-f5, a decision that struck me as a mistake, given that I could respond with 27 g4! After the game Hans labeled g4 the losing move and rattled off a bunch of long variations that I didn’t have the energy to follow or check. It turns out that I was right (it’s important to break up the e and f pawn duo), and he was wrong (black’s passed f-pawn isn’t as important as he thought), although I still didn’t manage to save the game: 27 … Kf7 28 gxf5 exf5 29 c4 (white’s queenside structure is not ideal for the creation of counterplay, to say the least) 29 … Kf6 30 cxb5 axb5:

There are two ways to try to create a passed pawn on the queenside: with the support of the king or with the support of the rook. I tried the former: 31 Kb3? Kg5 32 Rf2 f4 33 c4 Re3+ 34 Kb4 bxc4 35 Kxc4 f3 and black won shortly: the f-pawn is much stronger than the a-pawn and white’s pieces are uncoordinated and passive. However, 31 Rb4! would have saved a tempo and the game, since now 31 … Kg5 is met by 32 h4+, and 31 … Rc5 32 a4 bxa4 33 Rxa4 gives white just enough counterplay.

For a time, Hans’ strange ideas about this ending made me more willing to credit the idea that he was cheating; after all, how could someone who misunderstands rook and pawn endings in such a fundamental way be able to beat Carlsen just two years later? But if there’s anything that I’ve learned from watching the rise of America’s youth, it’s that a lot of growth can take place in just a couple years. Heck, I did it myself once upon a time, when my rating rose from 1359 in January 1995 to 1937 by January 1997.

Nothing about Hans really surprises me anymore. You could tell me tomorrow that he won the world championship or that he was banned by FIDE for life and I would hardly raise an eyebrow. He got swept up in what could and should have been a bigger, more nuanced conversation about cheating in chess but did himself no favors along the way. That said, he’s been playing great chess in 2024, and it would be an interesting poke in the eye of the chess establishment if he added a U.S. Championship title to his list of successes.

Well, since Capablanca.

Sam quickly got promoted from lessons with me to lessons with David Pruess, then Josh Friedel and Vinay Bhat. We sometimes joke about how the price of Sam’s lessons back then should have been future lessons with Sam as our coach.

Sam was leading the U.S. Championship around the halfway mark in 2018, and I sent him a congratulatory text, figuring that at some point he would fall back to earth. When he didn’t, and ended up winning the whole thing, I had to send an even more congratulatory text.

Assuming he was ever in danger at all.

Evidently something I have in common with Carlsen, although Magnus made short work of Hans in the speed chess championships.

Thanks for the local history lesson. I mainly remember the friendship/rivalry you had with Pruess back in the mid 1990s. I did meet Shankland at the Club you and David ran for a while on Virginia Street in the basement. As I recall, he presented a game of David P...a Najdorf, IIRC. But I missed Sevian and Niemann entirely, having "Retired" from chess in January 1998. Wish I hadn't stopped, but hindsight, ya know.