Balancing Act

How I got my groove back at the Berkeley Chess Club Championship.

I imagine that most experienced chess players have a metaphor that helps them think about what chess really is. An art, a science, a sport — for me, each game is a terrifying stroll into thin air towards another tightrope walker whose one desire is to knock you to the ground. How do you approach your opponent? Do you rush or lunge at them, putting your own balance at risk in the process? Or do you hang back, prioritizing safety above all else?

The element of risk, the need for harmony, and the potential for sudden catastrophe sums up my experience of playing competitive chess. Every move, every shift of the position involves tradeoffs: a pawn pushed to g4 weakens the h3 and h4 squares but might also signal an attack against the opponent’s king. The aesthetic value of a brilliancy is akin to an acrobat holding on by a single toe. And of course it’s all too easy to blunder and fall to the ground without one’s opponent doing much of anything at all. To play well requires grace and balance; play poorly enough and it can be hard to imagine anything other than falling off the wire.

I’ve spent a lot of 2025 staring at the ground, anticipating the next fall off the tightrope.

I don’t like to wallow in excuses for poor play, but it’s not surprising that I lost a lot of rating points in 2025. I was weighed down by the death of a childhood friend, terrible sleep habits, and teaching more classes than ever before, all while trying to wrangle my own three kids. Probably not the most opportune time to play multiple tournaments in a year for the first time since the pandemic. And while I sometimes played reasonably well for an entire game, each tournament was a new disappointment.

My solution was to keep playing while trying to be a little less invested in the outcome. During the Berkeley Chess Club Championship I stopped any tactical training and did only the most rudimentary opening preparation. My games in round two and three were extremely shaky — I could have lost both — but I scored 1.5/2 and played much better in round four, keeping my balance in a complicated game against an opponent I’d never beaten in our three previous meetings. Then I won in round five and round six and round seven, four straight victories against masters, the kind of chess I’d been playing back in 2014-15 when I was winning tournaments and hitting new rating highs at the end of almost every event. Despite drawing a completely winning position in round eight, I clinched first place with a round to spare, the kind of performance that I wasn’t sure I was capable of any more.

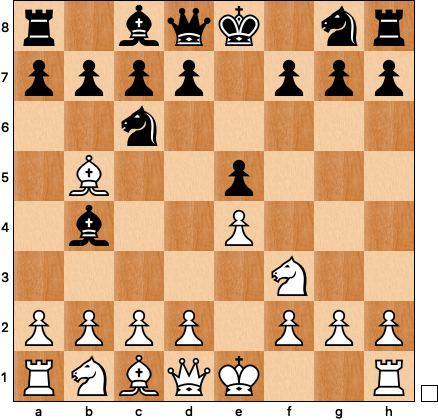

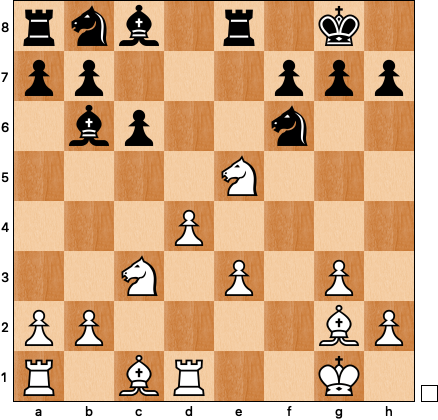

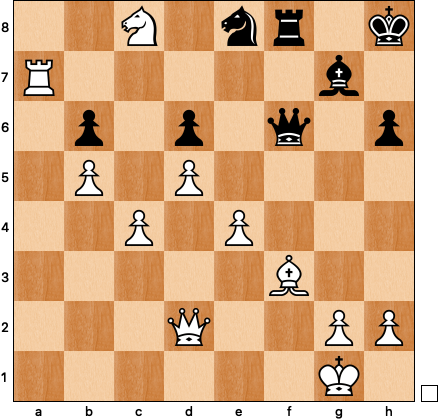

The key to keeping one’s balance begins with calm in the face of opening surprises. To illustrate: my seventh round game began 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Bb4:

What in the holy hell is this? You play chess just about your entire life and you think you’ve seen everything, but not this one, no no no. Is black really trying to lose a tempo to provoke white to play c3 and d4, moves that are more or less automatic in the Ruy Lopez?

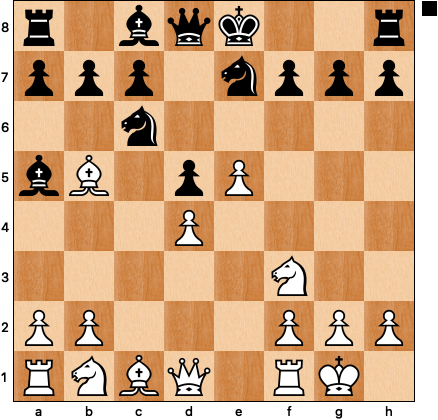

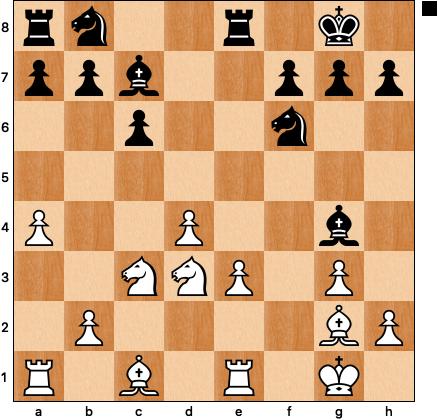

Even when confronted by something so confounding it’s important to take our opponent’s ideas seriously without losing our objectively about their merits. I played 4 00 relatively quickly (because castling is always going to be necessary) and after 4 … Nge7 began to get a sense of black’s idea. Imagine the variation 5 c3 Ba5 6 d4 exd4 7 cxd4 d5 8 e5:

Black’s position isn’t necessarily all that good, but his idea is clear: he is close to completing his development and then can hope to play against the d4-pawn in the future with Bg4, Bb6, and Nf5. I don’t think that there’s anything wrong with white’s approach, but I don’t feel totally comfortable in these types of structures, so I chose a different approach.

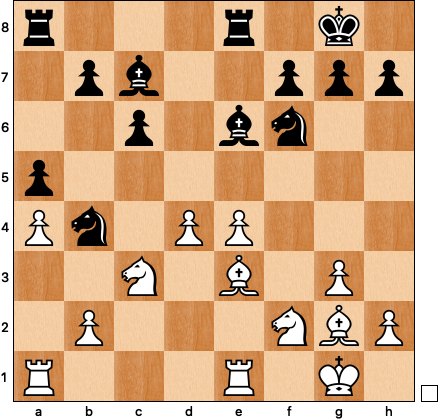

After the natural 5 c3 Ba5 I decided to harass the black bishop by playing 6 Na3!? d6 (6 … a6 seems like a logical improvement to limit white’s advantage) 7 Nc4 Bb6 8 a4 a6 9 Nxb6 cxb6 10 Bc4:

White is now significantly better: the bishop pair, better structure, and a flexible assortment of pawn breaks and middlegame plans are all in my favor. Taking the time to consider what black might be trying to accomplish with his third move helped me choose between a pair of tempting options, and I never lost control of the position.

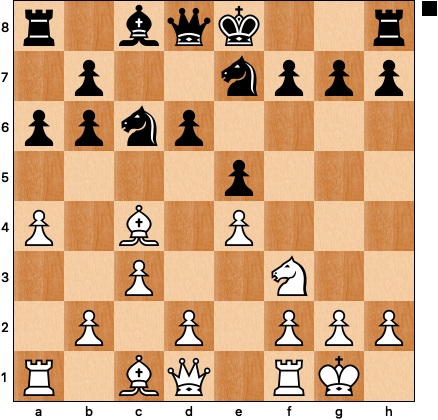

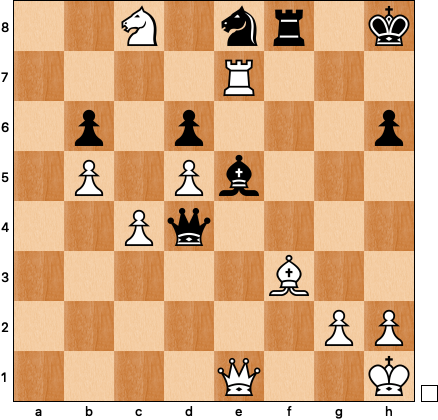

With the black pieces in round six I reached a queenless middlegame:

For the moment white can’t play e3-e4 because of Rxe5, so I was expecting 15 Nc4 Bc7 16 e4, when white has a bit of initiative. I didn’t predict 15 a4, threatening to soften up the black queenside with a5-a6, so I played 15 … Bc7, expecting 16 Nc4, the move I had been calculating earlier. Thus white’s 16 Nd3 also came as a second unpleasant surprise and any sense of serenity I was feeling evaporated.

Being surprised is as bad for the chess player as it is for the tightrope walker, and in addition to feeling flustered I was also annoyed at myself for not having considered Ne5-d3 — it’s not like this is an unusual maneuver in these kinds of positions. I played one more random-ish move, and after 16 … Bg4 17 Re1 decided that I should have a think:

White’s position is more flexible and he has a lot of ways to catch me off balance. One plan is queenside expansion through some combination of b2-b4-b5 or a4-a5. He could simply expand in the center with e4 and develop his queen bishop. Nc5, poking the weak b-pawn is another possibility, as is some combination of Nf4, e4, and h3, taking aim at my light-squared bishop.

The key to regaining one’s balance is to determine which plans are more dangerous and invest some energy into stopping them. I had a particularly hard time convincing myself that Nc5 wasn’t a problem, since I hate playing retreating moves like Bg4-c8, but 17 … Na6 is strongly met by 18 b4, and 17 … Nd7 allows both the queenside expansion plan and leaves the Bg4 low on squares.

That left me with a move that seems obvious in retrospect, 17 … a5!, fixing the queenside pawns before white can take control. White can play 18 Nc5, but here 18 … Bc8 is safe enough, and 18 … Na6!? is an interesting play for the initiative. My opponent blinked and played passively, and after 18 Nf2 Be6 19 e4 Na6 20 Be3 Nb4 and black is very comfortable:

Controlling the center with pawns is not unequivocally beneficial. In this case, black’s pieces play around white’s center and there are enough targets and weaknesses in the white position that I provoked a blunder only a few moves later.

And finally, a look at round five, from a position in which white is objectively winning:

I was once again feeling a little off-balance. I’d won a pawn, but had allowed more counterplay than seemed necessary and didn’t want to risk losing what felt like a safe and simple position just a few moves earlier. One way things could go wrong is 29 Bd4 f3 30 Bf1 Bh3 31 gxh3? Rg8! and black is suddenly winning down the g-file. With this in mind I played 29 f3, as allowing a protected passer on e3 is worth it if black’s attack is blunted. 29 … Qg6 renewed the threat of Bh3 as well as threatening cxb6, and converting the advantage is still a ways off: 30 Bf2 fails to 30 … e3, and 30 Bd4 Bh3 31 Bd1? Bxd4 32 Nxd4 Rg8 is a problem — white is struggling to contain black’s growing initiative.

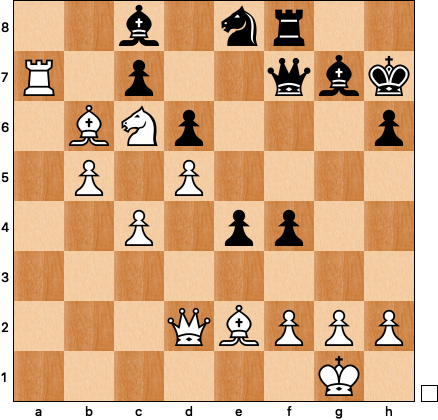

The student of history knows that a knight will respond when the king asks “Can no one rid me of this troublesome priest?” Thus 30 Ne7 Qf6 31 Nxc8 cxb6 32 fxe4 f3 (adding a little more chaos at the price of a pawn) 33 Bxf3 Kh8:

White is up three pawns, but I was still not enjoying my position. Black’s pieces are coordinated, threatening trickery on the dark squares. Mine are not: what’s rook doing now on a7? And the stranded Nc8? The computer says that there’s no need to rush, just Kh1 and h3 is fine, but it’s inhuman to sway precariously in the wind indefintely, so I settled on a plan of recoordinating my pieces and reestablishing balance.

I played 34 e5!? Qxe5 35 Re7 with the goal of getting my rook back to the first rank. After 35 … Qa1+ I had a moment of weakness, abandoning my planned 36 Re1 in favor of 36 Qe1, offering a trade of queens and hitting the Ne8. The problem was that I’d missed 36 … Qd4+ 37 Kh1 Be5:

One final wobble as white’s coordination is broken for the moment, but I fortunately found 38 Nxd6! Bxd6 39 Rxe8 and the three extra pawns are more significant than the opposite colored bishops.

After a round at the recently concluded London Chess Classic, Danny King asked Nikita Vitiugov if he felt happy about a position in which he had a small edge. Vitiugov answered in the spirit of the tightrope walker: “I was playing chess, so I was terrified!” Indeed, there are so many moments when a game can go off the rails: an opening shocker, a couple unexpected moves in the middlegame, the presence of lingering counterplay. Keeping a cool head and playing simple chess whenever possible does wonders. Here’s hoping I can keep it up in 2026.

Congrats on discovering your form again. Wow betide the rest of us who must face the real Andy Lee in 2026.

Love the George and Martha picture.