I am not a regular diner at the Cheesecake Factory, which might explain the shock I feel every time at the sheer size of its menu. Does a restaurant, even a chain restaurant, really need to serve steaks and burgers and pizza and salads and pasta in so many different versions and variations? And don’t even get me started on the dozens of varieties of cheesecake on offer, each one more calorie-laden than the last. It’s basically impossible to decide what to get, and I never end up feeling like I’ve made the right decision.

In my head I call this overabundance of choice the “Cheesecake Factory problem” although it of course has a real name, the rather bland and less calorically bountiful “choice overload.” It turns out that people prefer to have some choices, but too many are counterproductive, particularly if the many options seem more or less comparable in the mind of the chooser.

The original Cheesecake Factory problem is a problem of my youth, back before I had kids that would scream and throw food if we tried to take them out to eat in public. My new Cheesecake Factory problem is tied to how I choose my chess openings.

Back in the late 1990s, Kurt Jacobs was one of the regulars at the Berkeley Chess Club, the publisher of the weekly club bulletin, and a bit of a chess mad scientist. At one point he invented something he called the chess dice, which he would roll before each game to select what opening he should play. As a firm believer that a small set of openings were meant to be studied and refined over a lifetime of practice, I was horrified by his cavalier attitude; it wasn’t until I was much older that I realized that I needed to become adept in a much wider variety of structures than my beloved French Defense and d4 openings if I was going to keep improving. I ended up changing all my openings in the 2010s, learning king pawn (and with black, double-king pawn) openings on the fly. It was an important step forward for my chess development; I doubt I would have hit 2400 USCF without it.

Times have changed and I play a lot less frequently than I used to, which means that I have trouble motivating myself to maintain my knowledge of the openings I used to know well. I tend to see all chess openings as relatively interchangeable anyway: the results at my level are overwhelmingly about tactical vision and stamina and good form rather than what opening was played. And so I find myself picking out a new set of openings pretty much every tournament I play in, with greater decision-making agony each time around. This came to a head before my last tournament, the USAT East, when I had so much trouble choosing what to play that I prepared almost nothing at all and found myself in some real trouble right out of the opening in both games that I lost.

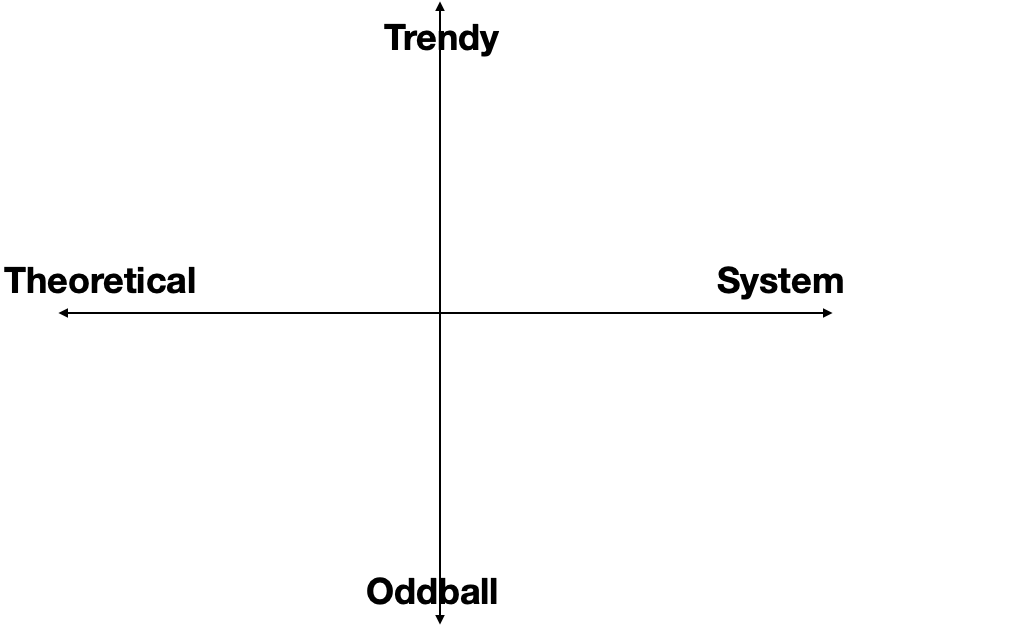

I’ve been thinking lately of chess openings as all existing on this set of axes:

The x-axis measures the sharpness of the variation. The left end requires the spaced repetition of innumerable Chessable courses, over on the right you basically just need to know where the pieces should end up. The y-axis is a popularity scale whose details may change over time but is otherwise rather consistent: the Benoni is never going to be as popular as the Ruy Lopez, no matter how much we may wish it to be so. Most openings are pretty easy to locate in one of the four quadrants. Najdorf Sicilian? Theoretical and trendy. The London is a trendy system (duh, it’s in the name), particularly at the amateur level. The King’s Gambit is theoretical but also more of an oddball choice these days, whereas something like the Hippo is both strange and highly systematic.

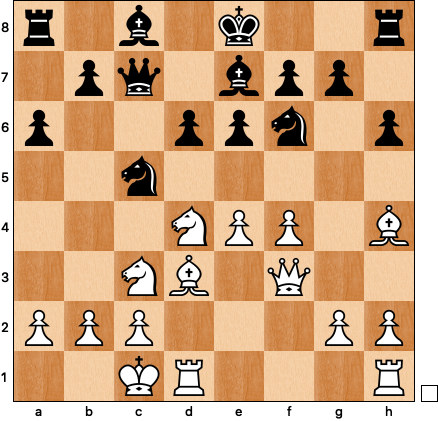

When I was playing more frequently about a decade ago, I played mostly openings that were both theoretical and trendy, the kinds of variations that demand a fair amount of work but in return often lead to good positions. Consider the following example:

We’re playing a sharp line of the Najdorf, and my opponent just erred with Nd7-c5. Even so, it’s a bit surprising how quickly her position falls apart: 12 e5! dxe5 13 fxe5 Nxd3+ 14 Rxd3 Nh7? (another mistake, now it’s over) 15 Bxe7 Qxe7 16 Nc6!

The knight is immune, but 16 …Qg5+ 17 Kb1 is no better, as 17 … 00 runs into 18 h4! Qf5 (or Qg6) 19 Ne7+ picking up the queen. After 17 … Bd7 18 Rxd7! I won in a rout.

That was the old me, but in recent years my opening preferences have migrated to the other three quadrants: systems with the white pieces, and theoretical-oddball openings with black.

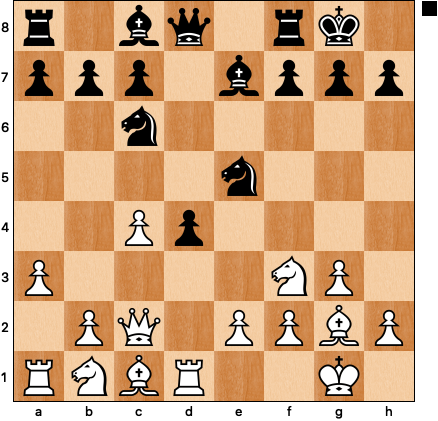

My favorite opening for some time has been the Albin Countergambit, whose objective evaluation is as dubious as its peers in the lower-left quadrant, but whose surprise value is unsurpassed. Here’s an example against Jack Zhu, one of California’s many young masters:

White’s play looks reasonable; he’s trying to gang up on the d-pawn, but his refusal to trade on e5 has left him tactically exposed: 10 … d3! is very annoying, as 11 exd3? Nxf3+ 12 Bxf3 Nd4 wins a piece. After 11 Qd2 Bg4 I was much better. In a more normal opening he’d probably be much more familiar with the tactical themes, but here he was caught off-guard and I was able to seize the initiative from the start.

The problem with this quadrant is that it’s hard to be comfortable playing the same variations over and over again: what if someone shows up truly prepared? I dodged a bullet against Justin Sarkar in the USAT East a number of years ago when he got his move order against the Albin mixed up, and I’ve been reluctant to play it in tournaments in which the pairings go up well ahead of time, such as at the Tuesday Night Marathon at the Mechanics Institute.

If the theoretical-oddball quadrant is one type of laziness (I’ll get a sharp position but I won’t have to learn a ton of mainstream theory), the systems approach is another: I’ll get a playable position no matter what, and I won’t have to devote much time to study.

Last summer my choice was 1 b3, fully embracing my inner weirdo. This didn’t work out quite as well as I’d hoped, but I found myself in interesting positions, and I was excited to keep gaining experience in these lines. Then I lost a couple of blitz games in the following variation: 1 b3 e5 2 Bb2 Nc6 3 e3 d5 4 Bb5 Ne7!? 5 Bxe5 a6 6 Bxc6+ Nxc6 7 Bb2 Qg5:

This gambit isn’t a refutation, but it’s relatively sound and it yanks the game from the oddball-system quadrant to the theoretical-oddball quadrant in a way that makes me very uneasy: I don’t like the prospect of getting blown off the board if I make a mistake with the white pieces. And so in February I switched to a more mainstream system, the English with 1 c4, 2 g3, and 3 Bg2, more or less no matter what. I felt a little bored in my games with white, but I won all three, so at least the results were good.

There’s more to say about all of this, but my big takeaway is that my approach with white is very different from my approach with black, so much so that I’m basically living in two chess worlds in every tournament: one in which I put my pieces on reasonable squares and try to apply slow pressure when I’m playing white, and another in which I take big risks and calculate a lot when I’m black. My proclivity for oddball stuff means I’m frequently changing openings to be less predictable, but I’m never getting solid experience in any one variation.

The piece I wrote about Spassky last month convinced me that I should aim for something a little closer to the 10th world champion’s opening play: simple and classical, don’t try to be too tricky, put your pieces on good, aggressive squares so that you can take advantage of your tactical skills, whatever is left of them. This is going to require more work, but I’m planning to play a couple more events in the summer and the time it takes should be worth it. At the very least, it will hopefully narrow down my choices from the full menu to the specials of the day.

I really relate to this! I feel the Cheesecake Factory problem in many areas of my life — what to read, what to watch, what chess books to study...

My solution has been to pick one Chessable author and just learn their approach for White and Black. It's somewhat arbitrary, but it's worked out pretty well so far. I often feel the temptation to go off and learn another opening, but usually I can just think for a bit about how long it's taken me to become comfortable in THESE openings and it offers enough pause.

That being said, this post has given me the itch yet again...