When I began writing this blog a little over a year ago, I happened to be reading Rouge Street by Shuang Xuetao. The three novellas in this collection are lovely, a mix of mystery and magical realism that grapple with Chinese history but also tell the story of the decline of the industrial boomtowns of China’s northeast. Some of the greatest works of literature take a place and breathe life into it through invented characters and plots — Joyce’s Dublin and Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County come to mind — and Shuang’s talents in this area are considerable. I felt by the end of the final tale that I had traveled somewhere far away but at the same time very real.

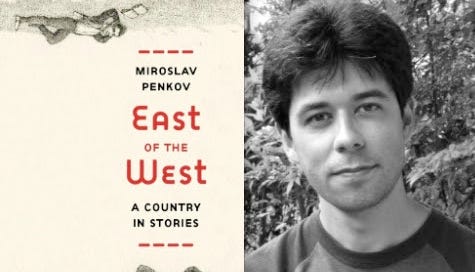

Miroslav Penkov’s East of the West has similar ambitions. It is subtitled “A Country in Stories,” as each installment revolves around Bulgaria: its history, its people, its continued meaning in the lives of those who, like the author, are expats.

I confess to not knowing a great deal about Bulgarian history. When most Americans think of Europe what they’re actually thinking about is Western Europe, and while I can claim a little more expertise give that I teach World History and took a class about Eastern European history a couple years ago, I have at best a hazy outline, largely cribbed from what I know about Poland and the former Yugoslavia.

I suspect that what makes Western European history so appealing is its relative simplicity. That place over there, the one that’s kind of pentagon-shaped, that’s France and the people there are French and despite revolutions and wars it’s been that way for a really long time. That’s obviously a huge oversimplification, and my apologies to any French readers of Lit & Chess, but it provides a certain contrast with the complexity of Eastern European history, which includes conquest by the Ottoman Empire and all sorts of nationalist wars and the assassination of a certain Archduke and a messy division of national borders post-WWI and the sites of Nazi concentration camps during WWII and the post-WWII Soviet bloc and then the fall of communism and so on and so forth.

Penkov’s stories move in and out of this history, recalling it in love letters and family stories and, in the title story, even flooded churches:

Then came the Balkan Wars and after that the First World War. All these wars Bulgaria lost, and much Bulgarian land was given to the Serbs. Three officials arrived in the villages; one was a Russian, one was French and one was British. East of the river, they said, stays in Bulgaria. West of the river from now on belongs to Serbia. Soldiers guarded the banks and planned to take the bridge down, and when the young master, who had gone away to work on another church, came back, the soldiers refused to let him cross the border and return to his wife.

In his desperation he gathered people and convinced them to divert the river, to push it west until it went around the village. Because according to the orders, what lay east of the river stayed in Bulgaria.

How they carried all those stones, all those logs, how they piled them up, I cannot imagine. Why the soldiers did not stop them, I don’t know. The river moved west and it looked like she would serpent around the village. But then she twisted, wiggled and tasted with her tongue a route of lesser resistance; through the lower hamlet she swept, devouring people and houses. Even the church, in which the master had left two years of his life, was lost in her belly.

The sweep of the river carries with it the inevitability of history that only someone very young or very foolish would try to fight. Penkov’s stories are filled with such characters, such as the young protagonist of “Cross Thieves” who urinates on a crowd of protestors, his cynical response to yet another attempt to replace one government with another.

My favorite example of this type is the hapless narrator of the final story, Mihail. After moving from Bulgaria to Texas, he loses his wife to a grossly rich and fat Bulgarian-American doctor. He treasures his time with his daughter and in one memorable passage teaches her how to play soccer:

“Always seek contact,” I say, “but if there is none, kick yourself to the ground. Make this a rule: you must dive for a penalty at least once every game.”

She listens, and like a great sport, runs, kicks her heel and rolls in the grass.

“It hurts,” she says and rubs her knee.

“What can you do?” I tell her. “Life.”

The bend of the river and the dive to the ground reveal an ideology of sorts. The rules of the world should be attacked and manipulated if at all possible, even if the attempt is likely to result in further pain. This approach to life is too much for Mihail’s equally hapless American friend John Martin, who tells the daughter that “you don’t win by tripping yourself and rolling in the grass.” Martin’s life was thrown into turmoil years before by his service in Vietnam, and his philosophy of life has little more to offer beyond the idea that you take responsibility for your choices and live with them, a hollow ethos for life in a damaged world.

One of the reasons that it’s so hard for these characters to “win” is that their situations are often reflections of the past, all those lost wars and land and children. Mihail’s story is called “Devshirmeh,” that is, the forced recruitment of Eastern European children into the janissary army of the Ottoman Empire. Mihail fights against the loss of his own daughter by telling her heroic Bulgarian stories; her acceptance of American culture through her mother is meant to mirror the assimilation of that of the janissary soldiers who were converted to Islam and made loyal to the Sultan.

Penkov likes to build tension in this way, linking the uncomfortable present to the painful memory of the past. He has no qualms about taking a bad situation and making it worse by adding a car accident or a tornado or an unwanted pregnancy. His stories can feel too busy at times, and I sometimes found myself wishing that he let the characters deal with one crisis before hurling another at them. The stories that work best are those that cohere at the end around an image or idea that makes sense of this melange of past and present, such as the conclusion of the first story, “Makedonija”:

I know that this will never be, but still I say, “Let’s go to Macedonia. Let’s find the grave. I’ll borrow a car.” I want to say more, but I don’t. She watches me. She takes my hand and now my hand, too, trembles with hers. I see in the apple the marks of Pavel’s teeth and, in the brown flesh, a tiny tooth. I show it to Nora and it takes her eyes a moment to recognize what it is they see. Or so I think.

But then she nods without surprise, as if this is just what she expected. Isn’t it good to be so young, she wants to tell me, that you can lose a tooth and not even notice?

The image of the tooth lost in the apple is our relationship with history in a nutshell. At first we’re too young to know that an apple could be anything but an apple, but to take a bite means to lose something of ourself in it. We are connected now, oneself and the apple, oneself and history. The knowledge it provides is permanent, there is no way to fight against it other than to accept that it is what it is — but to remember that it was once just an apple.