One of the great joys of modern chess is watching the games of Magnus Carlsen. Beyond his penchant for winning drawn endgames and ignoring dress codes, I particularly appreciate Carlsen’s ability to create order out of chaos, to find the exact right squares for his pieces in almost every kind of position. In the past, Carlsen fans could watch him work his magic in all kinds of traditional events at classical time controls, from Wijk aan Zee to the World Championship.1 In 2025, you’ve either got to wait for Norway Chess to roll around in a month or tune in to the variant formerly known as Fischer Random.

Last year I wrote up a guess-the-move exercise from Carlsen’s victory against Caruana in Norway; I thought it would be fun to do the same thing from the start of one of the Freestyle games, working through the complex choices of the opening phase. And what better place to start than the first round of the knockouts, in which Carlsen took an early lead against one of my favorite rising stars, Nodirbek Abdusattorov.

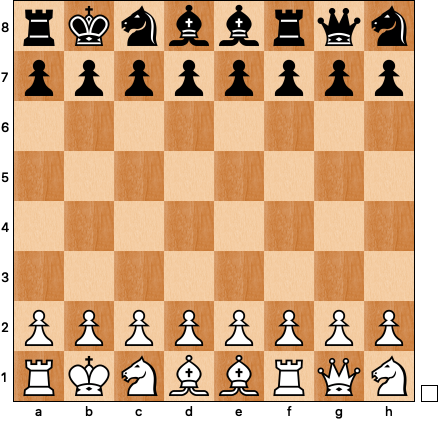

Here’s the starting position:

What’s going on? What are the opening priorities for white and black? How do you castle, anyway?2

Rather than do all the thinking myself, I decided that it wasn’t cheating to take a quick survey of the other first round games, which all started from this same position.

The most common opening was a gambit invented moments earlier by Nepomniachtchi, 1 e4 f5 2 exf5 g6. One of the cool features of these Freestyle events is how everyone playing the same color sits down to work out some collective opening ideas in the time between when the starting position is announced and the round begins.3 Nepo didn’t get to play his gambit, but Caruana and Nakamura were believers, and both managed to hold draws.

Keymer-Nepo began 1 d4 d5 2 Nd3 Nd6 3 f3 f5 which turned into a rather dull double Stonewall after it became clear that white could not break with e4. The 9th-12th place games were truly avant-garde: Praggnanandhaa-Vidit started 1 g4 g5 2 Ng3 Ng6 3 a4 a5, while Rapport decided to not waste on the kingside and opened 1 a4, leading back into the Nepo Gambit after 1 … a5 2 e4 f5. White won both.

The big picture is that white has trouble getting the ideal pawn center because it’s hard to control and/or maintain a pawn on e4; as such the starting position does not appear to be one of the most dangerous for the black side. The most difficult piece to develop is the queen rook, as castling kingside will take a while and castling queenside weakens the a-pawn, which can be targeted by the queen from her starting square. This helps explain the fact that in all five non-Carlsen games the a-pawns met at a4 and a5. Allowing white to play a4-a5 (or black to play a5-a4) unhindered could lead to some long-term development problems for the unwary player.

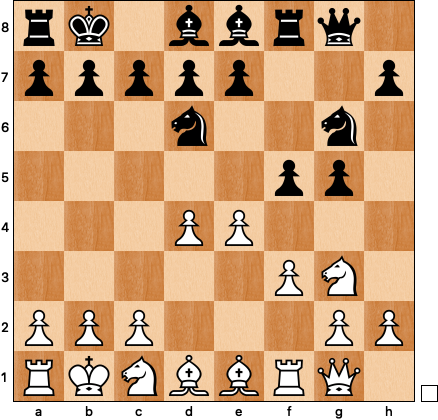

Predicting the opening moves of any game is a fool’s errand, but armed with my knowledge of the other games, I decided that Carlsen would go with the majority and play 1 e4. I was wrong: the game opened 1 d4 f5 2 f3 (I considered this as well as Nd3, e3, and a4) 2 … g5:

One of the things I noticed as I got deeper into this exercise was just how bad I was at predicting Abdusattorov’s moves. I assumed that he, like Nepo, would play 2 … d5. It seemed very risky to allow white the big center. But after seeing the g5-push, I began to wonder if pushing e2-e4 was even the right idea: there are a lot of Freestyle positions where pawn advances that look thematic to the classical chess brain are actually serious mistakes. As soon as white pushes e4, he has to contend with some combination of trading on e4, Nd6, and Bg6, immediately targeting the center.

It took me a few minutes to decide that white’s position was safe enough, and indeed, Carlsen did play the anticipated 3 e4. There followed 3 … Ng6 4 Ng3 Nd6 offering up another interesting choice:

Black is working on a pseudo-Alekhine Defense, perhaps hoping to induce 5 e5 Nc4. I’ll admit that I rejected this variation because I was afraid of 6 b3 Na3+, a good placement for a black knight when the bishop starts on f8, but not so much here when 7 Kb2 Nb5 8 a4 wins a piece. Rafael Leitao’s always excellent annotations suggested that Carlsen might have been wary of 6 … f4 (instead of Na3+), but 7 bxc4! is ultimately good for white. I picked 5 a4 with the idea of e5 and b3 next, but Carlsen chose 5 b3, allowing black to break in the center with 5 … e5. White does not benefit from opening up the game at this juncture, so 6 d5 was an easy move to predict, but I was once again surprised by black’s choice, 6 … h5:

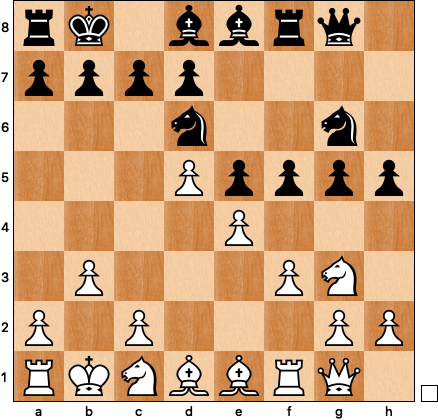

The position in the diagram demonstrates the difficulties inherent in Freestyle chess quite nicely. White’s trying to build up a big center in the classical style, so black responds by throwing everything forward on the kingside. There’s a potential trade of rooks if the f-file opens, a problem that you never have to think about in classical chess on move six, and it’s hard to figure out how to connect the rooks or get the bishops involved in the game.

I was undeterred and chose 7 Bb4, a superficial way of trying to win the fight over the e4-f5 squares. The problem is that after 7 … fxe4 8 Bxd6 cxd6 9 fxe4 black has 9 … Bb6 and some serious ownership over the dark squares. An elite positional player like Carlsen isn’t going to play like this (and honestly I’m surprised that I was willing to do so); he just expanded in the center and the next few moves played themselves: 7 c4 h4 8 Nxf5 Nxf5 9 exf5 Ne7:

White has prioritized space and structure over development, and now it’s time to bring some minor pieces towards the center. It’s an area in which Carlsen’s choices are very instructive — he plays his next few moves balancing between creating his own plan for harmonious development and inconveniencing his opponent. I am not so subtle or harmonious, and wrote the following notes about the position:

Black is getting the pawn back on f5, the knight will be strong, he’s planning to play d7-d6 to cement the pawn chain. White’s king is loose, probably going to play a2-a4 later and Ka2. I want some combination of Bc3, Bc2, and Nd3-f2-e4. And maybe I need to play h2-h3 at some point. Gotta get pieces out, though, I’m not so fond of starting with a2-a4. Let’s play 10 Bc3 to force d6, then Nd3.

I don’t think that this is a terrible plan, but Carlsen had another idea in mind that I completely missed. He started with 10 Ne2 Nxf5 11 Bc2, a pair of moves that I did not consider together, as the plan of Ne2-c3-e4 allows black to play Nd4, hitting the Bc2. Abdusattorov played 11 … d6, a move criticized by Leitao as being too cooperative (Be7 and b6 to play for Bc5 would have been more active), and now I was very surprised indeed:

Maybe it’s obvious why white would start by moving his Nc1 and Bd1, but I had genuinely forgotten that 12 000 was still on the table.4 So that was the point of this whole thing! It would be nicer if you could castle by leaving the king on b1, but even so connecting the rooks gives white a nice lead in development. Black’s Ra8 is not so close to influencing the game. Abdusattorov played 12 … b6, and now I guessed Bf2 for white’s next two moves, first incorrectly, and then correctly: 13 h3 (ah, yes, I had this in my notes earlier) 13 … Bg6 14 Bf2 Bf6:

White is now in the business of trying to provoke Nd4, so I glanced at 15 Nc3 Nd4 16 Bxd4 exd4 17 Ne4 but realized that this would all make more sense with a rook already on the e1. Carlsen was thinking the same way and the game continued 15 Rfe1 Qg7 16 Be4 (another correct guess, white’s not really in any serious rush) 16 … a5 (or wait, maybe he is now):

I wrote, “There’s really no reason to allow a5-a4” and confidently decided on 17 a4. Carlsen zagged and played 17 Nc3, setting his plan in motion without permanently shutting down black’s counterplay. For the moment this isn’t a problem, as the Nc3 covers a4, but after Nd4 Bxd4 exd4 the Nc3 will have to move and a5-a4 is back on the table. There was basically zero chance that Carlsen played Nc3 with the intention of continuing Na4, so he must have thought less of black’s chances on the a-file than I did. Abdusattorov replied with the expected 17 … Nd4.

White is happy to trade the light-squared bishops for a number of reasons, most importantly freeing e4 for his knight, so the next move pair was simple, 18 Bxg6 Qxg6. Now, rather than putting into motion the variation I expected, 19 Bxd4 exd4 20 Ne4 a4 21 Nxf6 Rxf6 (21 … axb3 22 Ne4 bxa2 23 Kb2 seems safe enough) 22 Qxd4 axb3 23 axb3, Carlsen started with the simple 19 Ne4. This choice helps answer the question of why Carlsen avoided a2-a4: had he played it, his b-pawn would now be hanging.

Abdusattorov’s bid for counterplay, 19 … a4, was met by 20 b4, keeping the queenside closed.5 He now stepped out of the double-minor piece trade with 20 … Bg7, bringing us to another interesting moment:

I wanted very much to play 21 a3, limiting the range of black’s rook and securing the b2 square for the white king. The problem is that this square isn’t all that desirable with black’s bishop lurking on g7. Carlsen anticipated another exit for his monarch: after taking on d4 he can wander out on the light squares, to c2 and perhaps b3 if needed. This idea is better with the white queen controlling some light squares in the center, so he played 21 Qf1 a3 22 Qd3 — I got the first move wrong but correctly guessed the second once Carlsen’s intentions were clear. Black is running out of tricks against white’s slow positional buildup, but Abdusattorov had one more idea up his sleeve — 22 … Bh6:

If 23 Kb1 Ra4 24 b5 Rb4+ 25 Ka1 g4! looks dangerous — imagine 26 fxg4 Rxf2! 27 Nxf2 Qxd3 28 Nxd3 Nc2#! I picked the same move as Carlsen, 23 Bxd4, but was briefly concerned about 23 … g4+ 24 Be3 gxf3 25 Bxh6 Qxh6+, only to realize that after 26 Qd2 white seems to be holding. Abdusattorov agreed, and the game continued 23 … exd4 24 Kc2 g4. I was not expecting this sacrifice, a testament to seriousness of white’s positional advantage, and chose 25 hxg4 over Carlsen’s 25 fxg4.6 Abdusattorov had one final surprise in store, 25 … 00:

And so, once again, I was caught off guard by the castling rules of Freestyle chess, in this case a mad teleportation across the very dangerous middle of the board by the black king. Let’s leave it here: despite black’s long-distance castling, white’s position is winning with proper caution and technique, which Carlsen has to spare.

I think it’s notable how easily Carlsen reached a winning position without doing anything particularly spectacular or strange. Rather than give in to the oddness of the starting position, he imposed his will, reached something analogous to a King’s Indian, and pushed a very strong opponent off the board. No need for a4 or g4 in this game, just high level position chess that, at least in this instance, is no less instructive Carlsen’s approach in traditional chess. If only — sorry David! — the castling rules made sense.

The country club, so to speak.

This will be relevant later, trust me.

I didn’t really understand why these tournaments were being held as knockout events until thinking about the role played by pregame collaboration. In a round-robin you could find yourself half a point behind the tournament leader, playing the same color in the final round, which would preclude working together and create some awkward choices for the other players who wanted to prepare together. In a knockout your only rival is the person you need to beat to make it through to the next round, so everyone playing the same color can share ideas without worry.

On a recent Chess Dojo podcast Jesse Kraai complained that the castling rules in Freestyle are too confusing — and David Pruess disagreed with him strongly — but I think that this is the kind of situation that Jesse was talking about: there’s so much weird stuff going on in the opening of Freestyle games that the cognitive load makes you miss things that you would normally expect to notice.

I still wanted Bxd4 and Nxf6 before pushing b3-b4. Carlsen’s patience is really instructive. His position advantages aren’t going anywhere; in fact, they’re increasing as Abdusattorov tries to find counterplay.

25 hxg4 is fine, but it’s helpful to find 25 … h3 26 Ng3! winning on the spot.