Last week I wrote at length about a rook and pawn ending that Carissa Yip could have saved in the first round of the Cairns Cup. Like so many endings, one big question for the defender was whether she should seek activity or defend passively. I’d like to return to that question in this post with a more general argument about how to think about inferior endgame positions.

First of all, I think the active vs. passive dichotomy is misleading. If we’re trying to defend, what is our purpose in gaining activity? What does it mean to be successfully passive? I prefer the words “containment” and “counterplay” instead, with the following definitions:

Containment means preventing the opponent from queening a pawn by any means necessary, whether by fortress, liquidation, or some intermediary technique such as the Philidor position.

Counterplay abandons the plan of stopping the opponent’s pawn and replaces it with the plan of queening one of our own.1

I like that these terms describe a logical goal rather than an arbitrary course of action, although it’s worth noting that in many complex endgames the defender often has to shift from containment to counterplay or vice versa.

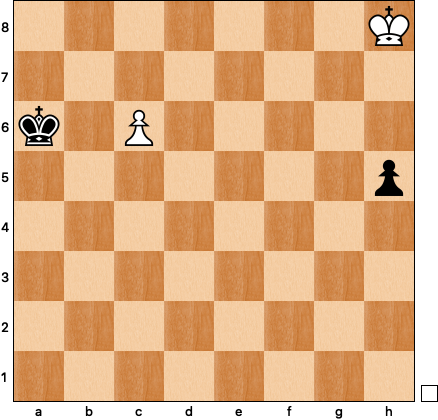

It also just so happens that these terms work to describe Reti’s famous king and pawn endgame study:

By playing 1 Kg7, white keeps both options open: the containment defense (getting back within the square of the h-pawn) and the counterplay defense (escorting the c-pawn to the queening square). After 1 … h4 2 Kf6 Kb6 3 Ke5 black is out of options. Taking on c6 allows Kf4, but h3 allows Kd6; either way the draw is secured.

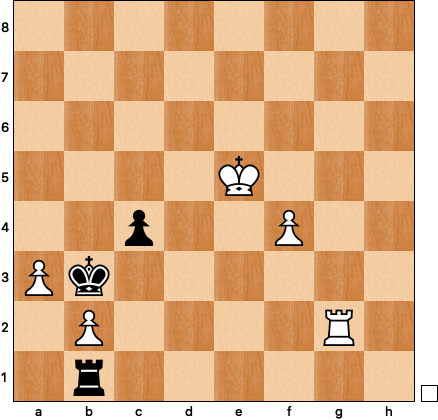

Here’s a more complex but far less elegant example from one of my own games. The overall quality of play is quite poor, but the mistakes are understandable — and easily corrected with a better understanding of counterplay and containment:

White is much better here thanks to his extra pawn and chances on the kingside. He could have won right away with 46 h6! but was likely concerned about black’s counterplay on the queenside. The only way to deal with a counterplay defense is to carefully calculate the variations, and 46 … Rd72 47 d6! Kb3 48 Re7 Rxd6 49 Rxh7 Kxb2 50 Rc7 c3 51 51 h7 Rd8 52 Kh4 c2 53 Kg5 is a winner:

White played instead 46 hxg6? and the game continued 46 … hxg6 47 Re6 Rxd5 48 Rxg6 Rd3+ 49 Kh4, which is where the fun begins in earnest:

Let’s try to imagine two possible defensive solutions, one based on containment, one based on counterplay:

Containment: trade the c-pawn for white’s queenside pawns and then rush the king back to the kingside in time to help stop the f-pawn.

Counterplay: win white’s b-pawn without giving up the c-pawn and rush to queen.

Once again, calculation is needed to be certain of which plan works better, but the complexity of the containment narrative should lead us to regard it with suspicion. Let’s rule out 49 … c3 for now as a bad plan, but that leaves some choice about how to go about the counterplay solution. The most obvious is 49 … Kb33 with the following variation in mind: 50 Rb6+ Kc2 51 Kg5 Rb3 52 Rc6 Kd3 (can’t give up that c-pawn!) 53 Kxf5 Rxb2:

The a-pawn is a non-factor given black’s advanced passer, and the draw should be easy to achieve. Sadly, I did not play this move, but instead chose 49 … Rb3?

There’s only one explanation for moving this already active rook and refusing to activate the king: I was actually playing for containment, more concerned about white’s extra queenside pawn than I was about the improbability of my king ever getting back to defend the kingside. White should now leap at the chance to liquidate the dangerous c-pawn, removing any hope of counterplay: 50 Rc6! Rxb24 51 Rxc4+ Kxa3 52 Rc5:

Apparently it was not obvious to me at the time that this position is easily winning for white. The problem is that there is no good way for black to stop white from reaching the Lucena position or something close to it. Black’s king is just too far away from the action to make a difference.

However, my opponent played 50 Rg2?, continuing the comedy of errors:

On its own, there’s a certain logic to this move. Despite accomplishing white’s single strategic goal, 50 Rc6 “loses” a pawn immediately, whereas Rg2 does not. With the queenside protected, white can return to his plan of Kg5xf5.

Except … black still has just enough time to switch plans: 50 … Rf3! 51 Kg5 Kb3 52 Kxf5 Rf1 53 Ke5 Rb1:

White doesn’t want to play 54 f5 Rxb2 when black’s counterplay is sufficient, so 54 Kd4 is a good try, hoping to prove that black can’t quite win the b-pawn. The position that arises shows the need to flexibility pivot between containment and counterplay, as 54 … Rd1+ 55 Kc5 Rf1 aims to contain white’s dangerous f-pawn. There could follow 56 Rg4 Rc1 57 f5 Rf1 58 Rg5 Rf4 and black is back to counterplay.

This would have been a nice save, but having missed the relatively easy defensive resources I was not up to finding something so difficult and played the insipid 50 … c3?, taking the liquidation of c-pawn into my own hands. I was pinning my hopes of containment on 51 bxc3 Rxc3 52 Kg5 Rc5:

I’m worse at chess in some ways than I was back in 2008, but I’m definitely better at correctly assessing the hopelessness of this kind of position. White can break black’s containment easily with Re2-e5, or as he chose in the game, 53 Rg3, saving the a-pawn before Re3-e5.

Dvoretsky would label this ending a tragicomedy, and indeed it was, but I think that it nicely demonstrates the importance of understanding both kinds of defensive ideas, containment and counterplay, and accurately implementing the correct one.

I’m playing some tournament chess throughout July, so hopefully I’ll have some interesting games to write about here in the coming month, as well as a variety of novels. Thanks, as always, for reading.

The inspiration for thinking about endgames in this way came after I botched a few in the late 2010s. I told myself that I was going to write a book about endgame play, analyzed just about every competitive endgame I’d played in my entire life, and then didn’t finish the book. Perhaps this post will be the catalyst and I’ll return to it this summer.

46 … Kb3 comes out to more or less the same thing, although here it’s important to find 47 Re7 Kxb2 48 Rxh7 c3 49 Rb7+! to deflect the black king.

It’s interesting that 49 … Rf3 50 Kg5 Rg3+ 51 Kxf5 Rxg6 also holds, but less instructive in terms of grappling with the problems of the rook endgame.

The tactical justification for white’s last move is 50 … Kb5 51 Rc8, protecting the b-pawn thanks to the skewer on the b-file and leaving black with no good options.

Great post! For all who want to practice out the position, the FEN is "8/7p/3r2p1/3PRp1P/k1p2P2/P5K1/1P6/8 w - - 0 1".

I love the clarity and adaptability of this schema. It's akin to an endgame version of Aagaard's 3 Questions -- a simple way to wrap your mind around a complex situation.