I watched the first thirteen games of the world championship match in more or less the same way. I would wake up around 6:30 Pacific, open chess-dot-com and play quickly through the previous night’s game to get a sense of what happened. Then, over breakfast, I listened to snippets of the Chess Dojo live broadcast, skipping around to check out how the trio of commentators assessed the key moments. We called this sort of thing dramatic irony back in English class: I knew the result and changes in the evaluation, whereas David Pruess, Jesse Kraai, and Kostya Kavutskiy, working skillfully sans eval bar, did not.

That was all well and good for the first thirteen games, but the final game demanded something extra, a live viewing experience to capture the tension of the moment. I figured that I would be more motivated to wake up at 1 AM if I was committed to it, so I invited myself on the Chess Dojo broadcast1 and went to bed early to catch a few hours of sleep before the game began.

(A quick aside, different topic but similar theme: I was following the Warriors-Rockets game Wednesday night and went to sleep with the Dubs ahead by six with under two minutes remaining. I figured the lead was probably safe, and if not, I would sleep better not knowing the final score. When I rejoined the conscious world in the wee hours of Thursday morning, I discovered that the Warriors had managed to lose by a single point.)

Talking about live chess games with other strong players is a joy: your brain gets a workout without the actual stress of competition. As Yasser Seirawan is fond of saying, it’s always more fun to sacrifice other people’s pieces. David and I watched and discussed many live tournaments during our East Bay Chess Club days in the early 2000s and we did commentary for a few rounds of the Pro Chess League a decade later, so it felt like a mini-reunion as we teamed up for the first chunk of the game. In a world where computer analysis is everywhere, it’s both refreshing and terrifying to do commentary without the crutch of the eval bar. The Chess Dojo guys had been doing a really impressive job throughout the match, and I think we continued that trend last night.

One of the biggest differences between computers and people is the narrative quality of human analysis. The computer lives perfectly in the present moment, assessing only the position in front of it. While talking with the Chess Dojo crew, I was acutely aware of how we were all telling somewhat different stories about the game within the context of the match as a whole. These stories shifted as our convictions about the position wavered or changed. Here are some examples:

Ding’s last move was b2-b3, one of the ideas that Kostya suggested for making progress on the queenside. I was still comfortably following the narrative of Ding’s game 12 victory, and suggested that he was playing this position slowly on purpose, avoiding the immediate a3-b4-c5 plan until he developed his pieces fully.

And then someone in the chat suggested a move none of us had considered: 14 … Bxf2+!? Suddenly the position becomes very concrete, and we found ourselves wondering if Ding had just blundered away the world championship. Contextually, this wasn’t far fetched: Ding had missed a one-move win of the exchange in game 12 and the Qxc6 tactic at the end of game 11.

It turns out that after 15 Kxf2 Qf6+ 16 Bf42 e5 17 Qd6! leaves white ahead, but without the computer it just felt messy. Gukesh’s choice of 14 … a6 suggested that the bishop sacrifice wasn’t best, but the question remained: what if both players had missed it3?

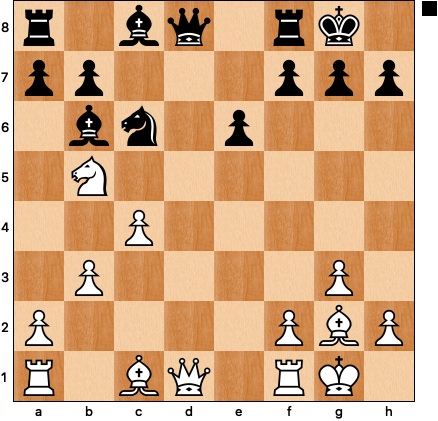

Despite these offstage tactics, Kostya, David, and I were optimistic about Ding’s chances at this stage of the game: black’s queen bishop has little scope, the b7-pawn is a potential long term weakness, the white knight can hope to land on d6. Jesse disagreed, calling b3 a soft move and arguing that black had full equality. Four moves later, the rest of us were inclined to agree with him:

One of my weaknesses as a chess player is that I often misevaluate dynamic factors by thinking of them as permanent features of the position. If my opponent is undeveloped, I imagine that they will always be undeveloped. In this case it’s notable how quickly Gukesh has taken over a share of the center, developed his troublesome queen bishop, and removed his b-pawn from the long diagonal: he solved the dynamic problems in his position very quickly. The trend seemed to favor Gukesh, and like Ding, we started looking for ways to slam on the brakes before black’s initiative grew.

At the time, I was proud of finding 19 Nf4, similar to the choice Ding made in the game: 19 cxb5 axb5 20 Nf4. But as it turns out, white had no need to simplify so readily. 19 Bxd4 Nxd4 20 f4! is a nice idea, meeting play on one side of the board with counterplay on the other and arguing that d5 is more secure than d4. There was no need to accommodate black’s active moves by agreeing to suffer. As you can see in the diagram that follows, by move 25 it was clear that the only one pressing was black:

Since the computer evaluation is almost certainly a misleading 0.00, Kostya suggested that we decide what percentage of the time we would expect a black win from this position. Jesse went with 50%, David argued that 7 or 8% was more realistic. That’s a major difference, one that I think is related to their narratives about the game so far. Jesse felt like black had been taking control of the position since Ding’s slow play in the opening. David earlier felt like white had been slightly better and hadn’t done anything seriously wrong, so he was now only slightly worse. The argument for black is that the pawn on a2 will be weak and that white’s king is insecure without the h-pawn: black can play for a future h5-h4 (or f5-f4) to loosen things up. The argument for white is that black can’t do much on the a-file yet, and an immediate Qd4 or Rd4 makes the kingside breaks hard to achieve.

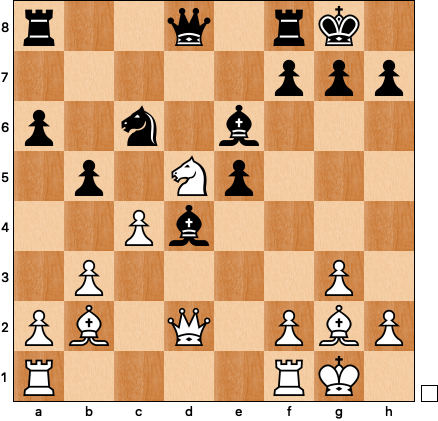

At this point I wondered aloud if white could simplify things further. Could he play a2-a3 to liquidate the queenside? Is the position still drawn even if the white b-pawn falls? I had apparently tapped directly into Ding’s willingness to grovel, as the game continued 26 a4 bxa3 e.p. 27 Rxa3 g6 28 Qd4 (take the pawn!) 28 … Qb5 (no!) 29 b4 (yes you will!) 29 … Qxb4 30 Qxb4 Rxb4 31 Ra8 Rxa8 32 Bxa8:

This brings us to the final piece of our narrative of this game, the story we had all been telling ourselves about Ding’s defensive acumen. We discussed how impressive it was that Ding didn’t both to protect his b-pawn, that he knew the position he was aiming for and made a beeline straight for it, the kind of decision a weaker player might struggle to make correctly. We took it for granted that Gukesh would press forever, given the stakes, and so we didn’t spend much energy questioning Ding’s approach, whether it was a good choice to aim for a position in which Gukesh could play on forever without risk.

Of course, this position is drawn, but it’s not as simple as a 3 vs. 2 ending with only the rooks or the same position with only the bishops4. Instead we turned our attention to Erigaisi’s wild game in the final round of the Qatar Masters and assumed that the tiebreaks were coming5. At time control, with 4 AM in the rearview mirror and a full day of work ahead of me, I decided to go to sleep. Jesse took his kids to school. Kostya took a nap with the soothing commentary of David Howell and Jovanka Houska in the background.

And so, for the second time that night, I woke up, this time at 6:30, to find that the result of a sporting endeavor I’d been following had suddenly flipped at the eleventh hour. The consensus of the flash analysis, more machine than man, suggested that Ding had missed chances to play for a win and later blundered under pressure. That’s objectively true in a sense, but it has little to do with the experience of analyzing the game in real time without a computer. The computer didn’t care about our subjective feelings about the trend of the position, but Ding was clearly feeling these trends as well. This led him to make a number of choices the computer would call suboptimal, but stuck us as pretty sensible.

My experience throughout the night was that the Ding of game 14 was the same Ding we had seen all match long. He got surprised in the opening, fell behind on the clock, and started feeling twitchy as soon as Gukesh activated his pieces. As Ding had done throughout the match, as soon as he became uncomfortable, he tried to make a draw. The only problem was after days and weeks of fighting a guerrilla war against a stronger, better-prepared opponent, he tried a little too hard to simplify the position, first with 26 a4, and finally with the tragic 55 Rf2??

I’ve been on the losing and winning end of similar mistakes countless times. We expect more from world champions, we assume that we can best understand their games with the help of the computer, but in the end they’re just as human as we are6, and our understanding of their chess is richer when we try to figure it out first on our own.

The context here is that I’ve known David for as long as the two of us have been playing competitive chess, 30 years at this point. Also I didn’t want him to be lonely broadcasting solo for the first hour until Jesse woke up at 5 AM Eastern.

I briefly wanted to try 16 Qf3 Qxa1 17 Ba3 Qxa2+ 18 Kg1, but David’s suggestion of 18 … Nd4 was too tough of a problem to solve. Upon further analysis, however, 19 Qh5! keeps white in the game.

Not terribly likely, but there’s precedent: Carlsen-Anand 2014, Game 6.

Which Ding had held the previous game.

Jesse was so sure it would be drawn that he briefly wanted to do the recap of the game before the game had actually ended.

And way way better at calculation and evaluating complicated positions and rook and pawn endings, etc, etc.

I tend to have little patience with overly strained narratives about chess, such as media portrayals of a chess game symbolizing the Cold War or racial relations or something. That always seems so strained to me. It's a game, not a metaphor.

That said, I found the Gukesh-Ding conflict to contain what I perceived to be something of a narrative of Human vs. Machine, of the rise of the digital era. I don't actually know the players very well, but the impression I got from watching a few recaps is that Gukesh was a monster of preparation. He seemed to blitz out his openings and be ready not five or six moves deep, but who knows -- 15 moves deep in any direction? That was readily apparent from the amount of time it took him on the clock -- almost nothing -- while Ding was taking an hour to evaluate on the board.

I have heard Magnus say that he views Ding as an intuitive player rather than a calculating machine, so that supports the narrative. (Speaking of whom, I do have the feeling as I've watched the last two world championship cycles that we are watching avidly all around the world to see who can finally and definitively lay claim to being the third and second best players in the world. While I totally get why Magnus got tired of the classical chess championship, I think his choice puts the dreaded asterisk on this whole affair. We don't know for certain what would have happened if Magnus had been prepped and played Gukesh, but I have grown to have a lot of confidence in the Norweigian)

So of course returning to the human-machine narrative: in Game 14 Ding fell apart in entirely human ways. Even I know not to put a bishop in the corner if you want to make sure it can find places to escape. I'm probably 1800 or so, but the rook blunder made even me flinch. I knew that as black I would have immediately traded of the rooks and bishops, but if you had asked me to swear that the two pawns beat the one with the kings in that position, I would have said "I'm not sure but it's certainly worth a try."

So when you say that champions are just as human as we are, I'm tempted to say that some are more human than others. Gukesh is obviously an, eating, breathing human, but at the same time his win is representative of a new era. He's the first champion brought up entirely in the era of elite engines. Sometimes it seemed as though he wasn't playing chess, he was playing computer moves from memory. Which isn't very fun, if true.

In all walks of life we now have to contend with The Rise of the Machines. There was recently an AI-created album of what if Led Zeppelin had been a 1950s band. That kind of thing I find quite repulsive. Art that is solely the creation of a machine isn't remotely close to art.

Which begs the question -- was the chess championship closer to a work of art or the moves of a machine? And down the road, are we going to see a lot of ultrapreparation meets ultrapreparation? Anyone with an appreciation for artistic chess blanches at the idea. That win by Ding, his second win, in I forget which game, felt like inspiration and innovation, and was really fun and thought provoking. We need more of that.

On the Warrior front, I was watching as the game unraveled and talk about your human errors, they were all over the place. The Warriors had the game in hand and made enough just mental mistakes that I'm still reeling and will not be able to speak any further of the matter until I've adjusted emotionally, which should probably come before the next world chess championship.

In the second-to-last paragraph, "the Ding of game 12" should be "the Ding of game 14", right? The impression I got was that game 12 was the closest that Ding came to his historical peak during this match.