It’s February, which means it’s almost time for the first leg of the 2025 Freestyle Chess Grand Slam Tour (hereafter abbreviated to FCGST) and endless reports about the pissing contest between Jan Henric Buettner, financier of the FCGST, and FIDE, increasingly desperate holders of the rights to all things chess, including, importantly, the title of all and any chess world championships. Perhaps Buettner could make the argument that Freestyle isn’t properly chess at all, that the shuffling of the eight pieces along the back rank creates an entirely new game — drop the “Chess” and let’s just call it the Freestyle Grand Slam (until he gets sued by the international swimming organization, that is).

In mid-January it seemed like a good idea to stop working on any normal chess practice and play as many Chess960 games on lichess as I possibly could. The main point was that this would give me greater understanding and appreciation when I tuned into the FCGST; it had the side effect of lowering my self-esteem dramatically. I hadn’t played any 960 for the past two decades, and it showed1.

What follows are some interesting moments, with ten big-picture takeaways thrown in for good measure, in case you don’t want to conduct the same trial by fire yourself. Let’s begin with …

Rule #1: The center is still the center.

It’s very tempting in 960 to get cute and attempt new hypermodern openings, particularly when one or both bishops are tucked away in the corners. Such an approach requires more care and attention than a simple put-pawns-in-the-center policy — there’s a reason that so many conventional chess games start 1 e4 e5!

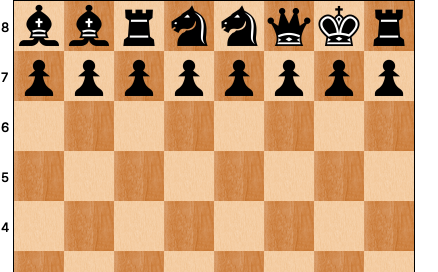

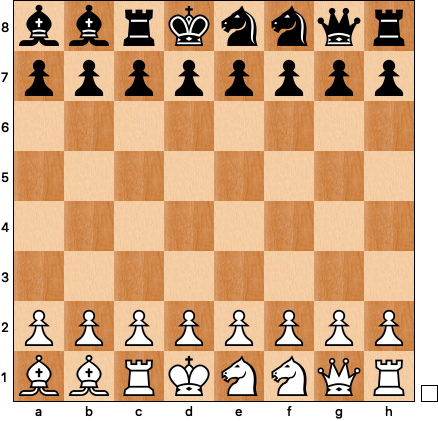

Here’s an example. With the bishops starting on the a and b-files, some kind of b3-c4 and b6-c5 structure is very likely, and the only question is how to execute this setup:

I had the black pieces, and the game began 1 c4 b6 2 d4 e6 3 e4. I’m sure I was already regretting having omitted the simple 1 … c5 or 2 … Nf6 to prevent white from getting everything he wanted in the center. The plan of playing d4-d5 against the fianchettoed bishop is a common one, even more effective in 960 when the Ba8 needs two moves to find another diagonal.

Blissfully unaware of any danger, I played 3 … Qe7, which I can only interpret now as a misguided desire to castle, which brings us to …

Rule #2: Castling is not always a priority, particularly when the king starts the game away from the center.

Is the black king in danger this early? No, it is not. Is it nice to connect rooks? Sure, but not when there are more important things to do, like, I don’t know, contesting the center2. The game continued 4 Ne3 00 5 b3 c5 6 d5 exd5, at which point the computer says white is +4, and why didn’t you play 6 … f5 and try to at least mix it up? The game continued 7 exd5 Be5 8 Bxe5 Qxe5 9 Nf3 Qh5 10 Nf5, which is all kinds of terrible and not going to get any better, so let’s wrap with a diagram:

It’s hard to imagine a worse result from the opening. It’s black’s queen against white’s entire army, a perfect example of how the side that controls the center controls the game, no matter what form of chess we’re playing.

Rule #3: The diagonals are where blunders happen; the bishops (and sometimes queens) are long-distance disrupters.

Consider, for a moment, the position in the diagram below. I’m playing white, having learned through hard experience that control of the center is the key to success, and I’ve caught my opponent in a hypermodern fever dream. Unfortunately, there’s a little problem:

It’s hard to believe that white’s in trouble here, but 3 … Qa6+ picks up one of the center pawns. If white blocks with either piece on d3, the d4 pawn falls, and 4 Ne2 drops e4. Fortunately my opponent missed this move, but after 3 … c5 4 Nf3 Qa6+ still works, as I had to play 5 Ke1, which left my king awkwardly stuck in the center.

These mistakes occur frequently because just about everyone playing 960 has too much experience playing old-fashioned chess. In the standard opening position the dangerous diagonal, the one which the pieces can’t block, is h5-e8 or h4-e1, and so we intuitively avoid weakening moves with both the f and g-pawns. In 960 the weak diagonals can be anywhere, and there’s no intuition to protect us from the sudden shock of a check that can’t be easily blocked.

Even with some practice under my belt I’m still bad at noticing these diagonals. Whenever my a2 or a7 is undefended at the start of the game I tend to blunder it (and then convince myself that it’s actually poisoned and that I’ve made a brilliant sacrifice). Here’s an even worse mistake:

I’m playing the black pieces, and apparently working on some sort of postmodern Dutch Defense. Structurally it makes sense to play 5 … b6, with the queen playing the part of the normally fianchettoed bishop, but 6 Ba6+ is an obvious refutation. You don’t win games, by resigning, so the game continued 6 … Rb7 7 Ne5 Bd6 8 Nxg6 Bxg6 9 f3 00 10 Bxb7 Qxb7 11 Nf1:

It’s time for another rule, not for something so gauche as “development wins games,” although that’s certainly the storyline after white wasted four of his last five moves.

Rule #4: The queen should be developed to a flexible post so that its counterpart does not dominate the early middlegame.

Compare the activity of the two queens. Better yet, compare them after 11 … f4! (a move I did not find) 12 e4 Nxe4! 13 fxe4 Qxe4, when the threat of mate on c2 is almost impossible to stop. In games when the queen starts on or near the corner, I found it wise to find a way to bring her highness to a typical center square (e2 or d2, for example), even if it cost me a move or two. You can survive a passively placed rook for quite some time, but not a buried queen.

Rule #5: Knights can create tactical problems on the fifth rank very quickly.

I think there are two main reasons for this rule. First, knights in 960 have quicker access to juicy squares on the fifth rank. Imagine a typical king pawn opening, 1 e4 e5. Now there are matching outposts for the knights on f5 and f4, and you’re probably familiar with the contortions the knights take to get there — in the Ruy Lopez, Nb1-d2-f1-g3 is just part of the typical schema of development. But in 960 a knight starting on d1, f1, or h1 can reach f5 in only two moves, just as a knight on a1, c1, or e1 can reach c5 in the blink of an eye. It turns out that g1 and b1 are the only starting squares that slow down the knights’ trips to these squares.

Secondly, sometimes g2/g7 or b2/b7 are undefended (or poorly defended) at the start of the game, which means that the trip to the fifth rank will come with a threat. Here’s a relevant example:

The bishops can’t start on the same color but the knights can, which leads to starting positions like this one in which they are sometimes complementary, attacking the same color square, sometimes redundant, stepping on each other’s toes.

The game began 1 g43 d5 2 d4 Nf6, which is a rather provocative move on my part, walking into a future g4-g5, but my opponent creatively decided to sacrifice the g-pawn: 3 Nb3!? Nxg4:

There are a lot of effective gambits in standard chess, and giving up a pawn on the wing for rapid development should be promising in a lot of 960 positions. The computer suggests 4 e4 dxe4 5 f3, with the point that 5 … exf3 6 Qxf3 forks the Ng4 and Qxb7#. My opponent found another interesting idea, 4 Qh3 Nf6 5 Nc5 Nb6 6 Ned3 e6 7 Ne5 Qe7:

Notice the rapid deployment of white’s knights to the fifth rank and the soft spot on b7, defended only by the black king. My last move was a blunder, but my opponent played the wrong version of the tactic, choosing to prevent future castling with 8 Na6+. It turns out that 8 Nc6+! would have been far stronger, as 8 … bxc6 9 Qa3 threatens both Qa6-b7# and Na6+ followed by Qxe7.

Next up is a corollary to rule #1:

Rule #6: Keep in mind that pawns can’t move backwards.

My opponent opened with 1 b4, an aggressive sally that I just don’t trust. In conventional chess, the b-pawn might be used to kick a Nc6, but in this tabiya black’s Nc8 is only two moves away from the potential weakness on c4. I’d learned enough by now to focus my attention on the center: 1 … f6 2 2 e4 e5 3 c3 b6 4 f3 a5 5 b5 Ng6 6 d4:

I was rightly happy with my opening play after 6 … d5, but I should mention that 6 … f5 is also possible, since 7 exf5 Nh4 (another knight to the fifth) forks f5 and the soft spot on g2. This brings us to another key point:

Rule #7: It’s often possible to strike back in the center in surprising ways not available or effective in standard chess.

In some cases the pieces are better able to support aggressive play (such as black’s Bg8 that covers d5 in the diagram above), in others the opponent’s pieces are not well placed for retaliation (imagine a Scandinavian Defense in which white cannot play 3 Nc3 to hit the black queen).

Here’s a final opening fragment, with a starting position similar to the first in this article:

I had the white pieces and started with 1 c4 b6 2 Nf3, having apparently learned nothing about benefit of building a big center against the Ba8; 2 d4 would have been more to the point. The game quickly heated up: 2 … d5 3 cxd5 Bxd5 4 Ne3 Bb7 5 b4 Nd6 6 h4 Ne6 7 Qh2 Qe8 8 00 Qb5:

There’s a couple of rules in play at once: both sides activated their queens in anticipation of a middlegame skirmish, and it feels like I’ve been hit by yet another unexpected diagonal move; on b5 the black queen hits b4 and e2. I played the awkward 9 d3, but the computer suggests that 9 h5! would have been a powerful alternative.

The point is that after 9 … Qxe2? 10 d3 Nxf3 11 Rfe1 Qd2 12 Bc3 traps the black queen. The alternative, 9 … Qxb4, is a long term sacrifice for positional compensation: 10 h6 f6 11 hxg7 Nxg7 12 d4 and white is much better, a surprising +2 according to the computer. This suggests the following:

Rule #8: Chess960 positions can become tactically difficult very early on, and …

Rule #9: Playing 960 dramatically increases the cognitive load of both players, making significant mistakes much more likely.

Towards the end of the “The Country Club and Circus” I compared Chess960 to the paintings of Jackson Pollack. The analogy isn’t quite right; 960 games are more similar to the works of Picasso, cubism brought to the chess board. That is to say, the pawns are in the right spots, but what is the nose doing way over the on the side of the face? It takes a little getting used to, but it’s worth remembering that there’s always light at the end of the tunnel:

Rule #10: The closer a game of Chess960 gets to the endgame, the harder it is to distinguish from classical chess.

A rook and pawn ending is just a rook and pawn ending, no matter how strange the starting position, which suggests that at the end of the day, all of this is just chess, not something unique or alien.

I hope this was a helpful guide to the kind of chess we’ll see in Weissenhaus, at both rapid and classical time controls4. Let’s close with a quick poll:

In my defense, in order to get in reps I was playing at all sorts of ridiculous time controls (2+1), (3+0), and I assume that almost everyone I was playing had a lot more 960 experience than I did.

Not to mention that the rooks are not even close to being connected here, given my evident disinterest in developing either knight.

Not my favorite opening idea; we’ll return to this issue in a bit.

Quick footnote rant: the rapid round robin to eliminate two of the ten players before the classical portion of the event begins is truly bizarre, a choice of format that seems to reward collusion between the top players to draw against each other and pick on anyone who is seen as weak or in poor form.

Mechanics' is hosting its first Freestyle tournament later this month (Feb 27), in case you can make time on a Thursday night to experience 960 OTB:

https://www.milibrary.org/chess-tournaments/chess960-thursday-night-rapid

I love your writing and this article is really helpful and on point