Groundhog Day

How I got trapped in the same endless rook and pawn ending, day after day after day.

September 28

The actor Andy Samburg and I briefly attended Berkeley High School at the same time. He was a senior, I was a freshman. We didn’t know each other, but later in life I enjoyed his movie Palm Springs, in which Samburg wakes up to the same day over and over again. Little did I know that I too would someday be trapped in a similar way, in the confines of a hideous rook and pawn ending.

The sun has set, the kids are in bed. I turn on the Perpetual Chess Podcast while I do the dishes. The most recent episode features an interview with Matt Gross, who recently made master after a seventeen year layoff from competitive chess. Matt’s first life in chess was in the Bay Area, and as coincidence would have it, we faced off in his final tournament before his hiatus in 2004.

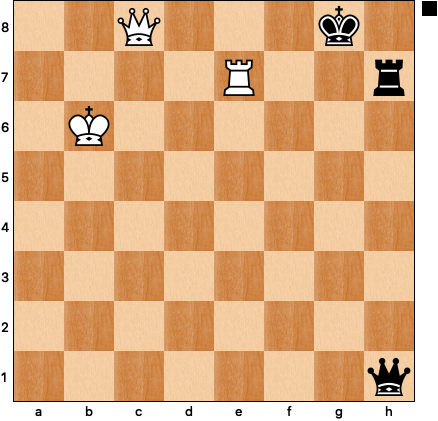

Matt’s story is interesting, particularly since his chess profile is similar to mine: heavy on tactics, low on positional acumen. Turns out he’s built a website, MoveLibrary, that captures a lot of the work he’s done since he returned to chess. I browse around for a bit, go to the rook and pawn ending practice page, and click on the first practice ending. It looks like this:

Matt’s site suggests practicing the defending side against Stockfish, so I give it a shot, despite the fact that black’s position is pure suffering. I survive for fifty moves before resigning, not too bad. This is in part because the computer spends a lot of time moving in circles before taking aggressive action, in part because I know enough about these types of positions to sacrifice the useless h-pawn right away in order to active the rook1.

I play the position a few more times in order to try out some bad defensive ideas. One obviously bad idea is to try to change the structure by pushing d7-d6, allowing a protected passed c-pawn. Another bad plan is to try to queen the h-pawn. The computer finishes me off with glee: 1 … Ke7 2 Kb5 Kf6 3 d5 Kg6 4 Re5 h5 5 c6 dxc6+ 6 dxc6 h4 7 Kb6 h3 8 c7 h2 (8 … Rh8 9 Rc5 h2 10 Rc1 Kg5 11 Rh1 Kg4 12 Rxh2 gives better practical chances against a human, but not against Stockfish) 9 c8=Q h1=Q 10 Qf5+ Kg7 11 Re7+ Kg8 12 Qc8#:

Having satisfied my curiosity about the uselessness of the h-pawn, I go back to sacrificing, but have trouble doing better than I did on my first attempt. I keep getting to positions where white sacrifices its c-pawn in order to infiltrate with the king:

The point is that after 1 Kf6 Rxc5 2 Rh8+ Kb7 3 Ke7 white will win the d7 pawn and achieve the Lucena position.

I go to bed feeling just annoyed enough to know that I’ll be taking another crack at the position tomorrow.

September 29

The tagline for The Edge of Tomorrow, in which Tom Cruise must battle aliens over and over on the same day, is “Live. Die. Repeat.” These words could also serve as the tagline for my struggles to survive against Stockfish.

The sun is up, which means it’s time to take another crack at Stockfish. Every game leads to the same hideous structure: white pawns on c5 and d6, black pawn on d7. My king is buried on c8. I try different ways of annoying white with my rook: going to the first rank to check from behind, leaving it on the fourth rank to cut off the white king from the action. Stockfish wanders around and then breaks its king free, winning over and over again.

Only once do I reach a new defensive position:

My rook cuts off the white king on the b-file. My king is alive! But the computer is lethal: 1 Ka6 Rb1 2 Rc7 Rb2 3 Rb7 Rc2 4 Kb6 Rxc5 5 Rc7! and my rook is trapped. I laugh at the absurdity of it all, shed a tear for this latest failure.

I decide that it’s time to cheat a little. Matt suggests on his website that the best way to learn these positions is to spar with Stockfish: take turns playing each side to get a sense of the optimal strategy for each side. In my infinite stubbornness I’ve been playing only the black side, but now it’s time to at least run the starting position through the engine to confirm that it is indeed drawn. It is.

Armed with the confidence that a solution exists, I try again, deciding that I will also run the final position through the machine. Same old pawn structure, same sacrifice of the c-pawn, same white king on e7. I resign here …

… only to learn from the engine that this position is actually drawn. Black has to play 1 … Rh5! to get the rook on the long side of the pawn and establish enough checking distance to hold. I know about this in a hazy sort of way, but apparently not well enough to keep myself from resigning when it appears on the board. It’s subtly different from the final position from the day before, as there white’s rook was already on the h-file, preventing black’s rook from gaining enough checking distance.

I reload the starting position and try again. For some reason I can’t seem to make it back to the long side draw; the computer keeps tricking me. I go to bed significantly more annoyed.

September 30

There comes at point in every Groundhog Day-like movie in which the protagonist, tired of flailing and flopping and frequently dying, decides to improve themselves, often by learning French or how to ice-sculpt in order to impress Andie MacDowell.

The kids are eating dinner. I flop down on the couch and grab a book off the top shelf. It’s Mark Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual, one of the single greatest guides to chess instruction. I find the section with the long-side defense (see previous diagram) and quickly learn it. The idea, assuming you don’t accidentally resign, is to prevent the passed pawn from getting to the seventh rank, which often involves checking away the enemy king and/or occupying the back rank with the rook.

Now all I have to do is find my way back to the long-side defense. I make a list of the things I’ve learned about the position so far:

There is no good way to alter the pawn structure or keep the h-pawn: the c5-d6 vs. d7 structure is going to happen, and it is miserable.

The black king belongs on the queenside to leave the kingside open for the long-side defense.

The black rook can check a bunch from the back rank and then sit on the c-file to annoy white. This plan seems accurate because the computer doesn’t rush to try to win: it just moves around in circles, which indicates that black hasn’t messed anything up, it’s still a draw.

The penetration of the white king to f6 isn’t decisive as long as the black rook gets to the h-file in time to set up the long-side defense.

Armed with that knowledge, I tell myself that I’m going to take it seriously this time and only play the computer once. I arrive at the position below, so similar to all the others:

White has just played Rd1-f1. I confidently leave my rook on the c-file: 1 … Rc2? only to discover that 2 Rf8+ Kb7 3 Rd8 and there’s no good way to protect the d-pawn. I resign in disgust but review this critical moment before starting a new game. I add one more thing to my list:

White can’t be allowed to bring its rook to the back rank with check. In response to white rook to the e, f, g, or h-files, black should generally play … Kb7!

We play again. This time, when the computer plays Rf1, I respond with Kb7. It tries Rg1 and Rh1 just to see if I’m paying attention. I survive to move 50, 60, 70 without even having to show my knowledge of the long-side defense. The computer does whatever the machine version of “getting bored” is and loses both of its pawns for no particular reason, forcing me to eventually stalemate it in a king and pawn ending. The curse is lifted! I can go one with my life!

October 1

After thousands of February 2nds, Bill Murray finally wakes up to February 3rd; after dozens of tries in September the calendar turns to October and I get to play the white side of the rook and pawn ending.

I waltz through the first day of October with a smile on my face, still happy that I survived against Stockfish the day before. But I still don’t feel like I truly understand the position. What if white plays for Rd8 as quickly as possible? Is the long-side defense necessary or can black defend more easily? There’s only one way to find out: play the white pieces.

I do not do well. I play similarly to Stockfish as white, but it springs an interesting idea that I had not previously considered:

Black has just played Rc1-e1. How is white supposed to proceed? If the rook leaves b5/a5, black plays Rc1 and forces it back. The king is cut off on the e-file and cannot help. I shuffle around for a bit and allow a draw.

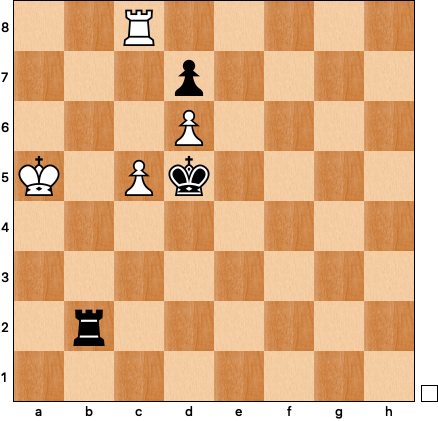

Time to try this with black. We reach the same position, it’s up to Stockfish to show me what to do: 1 Kf5 Re2 2 Kf6 Re1 3 Rb4 Rc1 4 Re4 Rxc5 5 Re8+ Kb7 6 Ke7 and we’re back to the long-side defense from three diagrams ago. Now it’s time to put my Dvoretsky knowledge to work: 6 … Rh5! 7 Kxd7 Rh7+ 8 Ke6 Rh6+ 9 Kd7 Rh7+ 10 Ke7 Rh8 11 Re6:

On last trap, and I fall right in: 11 … Rh7+? (only 11 … Kb6! draws) 12 Kd8 and the problem is that 12 … Kc6 13 d7 comes with check!

Ugh. One more try. This time I don’t bother with the e-file cutoff; I just go back to checking the white king from the first rank combined with Rc1 to target white’s only weakness. This time Stockfish swings its rook around to d8:

I play 1 … Rh4+ 2 Ke5 Rh5+ 3 Kf6 Rxc5 4 Ke7 Rh5! (long-side defense once again!) 5 Rxd7+ Kb6 6 Rd8 Rh7+ 7 Kf6 Kc6 and the game is soon drawn: white’s king cannot escape the checks from the h-file and hold the d-pawn.

Conclusion

I wrote up my struggle with this ending in order to help me understand it better and to force myself to work through it without letting Stockfish help me too much. These sorts of positions are incredibly hard to defend in practice because there are so many ways to go wrong and the strong side can just keep moving around in circles, waiting for a mistake. The tendency to drift into a losing position is strong, which is why I think it’s important to be able to articulate a clear drawing method, something that you can stick to that anticipates white’s best winning attempts. Here’s my best attempt:

Black begins by playing Kc7 and Rg7. The h-pawn has to be jettisoned in order to activate the rook. White will eventually have to fix the pawn structure by playing d6 in order to make progress.

Black’s rook is well-placed on the first rank where it can give annoying checks and drive either the white king or rook from their best posts. It can also target the white c-pawn from c1 or c2. There are other methods, such as cutting off the white king along the fourth rank or the e-file, but these did not feel as natural, although they also work. Black’s rook should always be far enough away from the white king to give a check or two.

Black’s king belongs on the queenside and will typically shuffle between c8 and b7 at various moments. The black king needs to move to b7 when the white rook threatens a check on the back rank.

It’s impossible to stop the white king from getting to f6 and e7. Black’s only defensive strategy at this point is to win the c-pawn and then quickly swing the rook back to the h-file to set up the long-side defense. The execution of this defense is not as simple as some other rook and pawn strategies2, so practice is recommended.

One difficult position down, a million more to go. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got another ending to play against Stockfish.

My technique in this endgame was pretty bad at times, but it’s nice to realize that I’ve internalized the idea that you can’t hope to survive a bad rook and pawn ending with a super passive rook. Giving up a pawn to activate the rook in the endgame is often the difference between gaining drawing chances and going down without a fight.

Such as the Philidor position.

Interesting post Andy, you've got more patience than I do. That Rc7! "trapping" the Black rook on c5 is a fun new pattern to keep in mind though.

That was a wonderful exposition of this method of endgames training: it made me want to do the same! Also, I'm impressed by your perseverance in trying to crack this endgame, day after day. Also, thanks for the recommendation of "Move List" resource, I'd come across it previously, but forgot by now, it's a very interesting one: I'm currently looking at his approach to repertoire building.