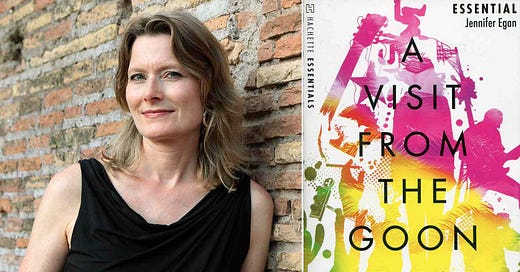

Depending on your point of view, A Visit From the Goon Squad is a novel disguised as thirteen short stories or thirteen short stories disguised as a novel. The first two stories introduce the two protagonists, Bennie and Sasha, before the novel expands into the lives of their friends, family, and rivals1. One of the pleasures of Jennifer Egan’s novel is how these stories fit together into neat little triptychs that follow a character across time and space, defining and then redefining them along the way. One of the frustrations is that we’re never anywhere for very long, and no character’s perspective is repeated as we move from story to story2.

Egan maintains a kind of internal consistency across the individual stories by doublings and pairings of characters, themes, and images. Two stories are told from the perspective of children about their parents, two decaying rock stars are granted second chances, paired chapters explore the chaotic youth and long-sought maturity of both Sasha and Bennie. Consider the following passages, which felt like a wink from chapter to another:

He would step through a living room strewn with the flotsam of her young kids and watch the western sun blaze through a sliding glass door. And for an instant he would remember Naples: sitting with Sasha in her tiny room, the jolt of surprise and delight he’d felt when the sun finally dropped into the center of her window and was captured inside her circle of wire.

and

He leaned in to the buzzer, every electron in his body yearning up those ill-lit angular stairs he now remembered as clearly as if he’d left Sasha’s apartment just this morning. He followed them in his mind until he saw himself arriving at a small, cloistered apartment—purples, greens—humid with a smell of steam heat and scented candles. A radiator hiss. Little things on the windowsills. A bathtub in the kitchen—yes, she’d had one of those! It was the only one he’d ever seen.

There’s a certain sense of nostalgia in each passage, a place frozen into memory by an unexpected delight that is suddenly brought back to life by a flash of the sun, a familiar stairwell. Together they also reveal the central theme of Egan’s novel, the ways in which time3 changes us all.

The most important—and in my mind, most irritating—doubling, tripling, quadrupling in Goon Squad is the overwhelming weight of mid-life crisis that permeates so many of the stories. The adult characters are adrift, unhappy, confused at how the dreams of their youth led them to where they are now. They struggle to understand their children. They steal and lie. They eat precious metals and go on safari. They look behind them, into the past, and in their pain lose something of themselves, as neatly captured by one chapter’s retelling of Greek myth:

Orpheus and Eurydice in love and newly married; Eurydice dying of a snakebite while fleeing the advances of a shepherd; Orpheus descending to the underworld, filling its dank corridors with music from his lyre as he sang of longing for his wife; Pluto granting Eurydice’s release from death on the sole condition that Orpheus not look back at her during their ascent. And then the hapless instant when, out of fear for his bride as she stumbled in the passage, Orpheus forgot himself and turned.

I ran out of patience for this pattern of nostalgia, loss, and crisis long before the end of the novel. This kind of feeling isn’t improved through repetition, and Egan’s return to it over and over again felt like a justification for the inclusion of some of the weaker and less connected chapters in the novel4. It’s also a reason for the non-chronological movement of the narrative, in which a character’s problems are established before moving backwards in time to reveal the underlying traumas that explain the character’s present damaged state, a kind of literary unpeeling of an onion that brings about tears more than it illuminates. It’s a popular technique—Nathan Hill does the same thing in his most recent novel, Wellness—but the whole effect feels to me like I’m sitting in on a therapy session rather than reading a novel5.

I ended up wishing that Egan had spent less time on the problem and more on the solution, which she hints at in the final chapters. In Chapter Twelve, “Great Rock and Roll Pauses,” Lincoln Blake’s obsession with moments of silence gives us another way of thinking about time and aging, one that contrasts with the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice: that people’s lives ebb and flow, that moments of silence do not necessarily mean an early conclusion to one’s life and dreams, one’s potential or usefulness. It’s a message that gets hammered home rather bluntly in the final chapter but could have been developed across a number of the other stories, perhaps if there had been fewer of them.

As I was reading I categorized these stories as part of the Bennie-verse or the Sasha-verse", depending on which character their were primarily associated with.

This is a biggest difference between Goon Squad and the similarly broken narrative of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, which brings each narrative full circle in the second half of the novel.

The “Goon Squad” of the title.

Specifically chapters 4, 5, 8, and 9.

In the first chapter of Goon Squad we literally are sitting in on Sasha’s therapy session, so there’s that.