Name Yer Tactics

Hook and Ladder, Scorpion's Sting, Gordian Knot, and the Babysitter Bishop.

I’ve been watching the London Chess Classic thanks to the combination of having last week off from work with the games starting at 8 AM Pacific. The broadcast has been delightfully free from computer analysis, and it’s been a pleasure to see grandmasters thinking about chess rather than explaining computer variations. The post-game interviews have also been insightful, and a good reminder that the kind of opening preparation done by the pros1 is very different from what’s necessary for amateur players.

I’ve written in the past about my lack of interest in memorizing opening lines, which is a little disingenuous given how much information about different openings is stuck in my head. But my games, like those of most people, are won by the player who more skillfully navigates the tactical and technical challenges of the phases that follow. There are a variety of good ways to increase one’s capacity for tactical knowledge and pattern recognition, but I wanted to suggest one that I don’t see written about very frequently: the naming of chess concepts.

Joshua Foer’s Moonwalking With Einstein is a great book for anyone interested in the journey from novice to master. Foer writes about the history of insights into human memory alongside his own burgeoning interest in memory competitions, leading ultimately to his victory in the 2006 US Memory Championships. There’s a lot of brain science mixed in, such as this passage about the challenges of retrieving a memory from the jumble inside our heads:

All of our memories are … bound together in a web of associations. This is not merely a metaphor, but a reflection of the brain’s physical structure. The three-pound mass balanced atop our spines is made up of somewhere in the neighborhood of 100 billion neurons, each of which can make upwards of five to ten thousand synaptic connections with other neurons. A memory, at the most fundamental physiological level, is a pattern of connections between these neurons….

The nonlinear associative nature of our brains makes it impossible for us to consciously search our memories in an orderly way. A memory only pops directly into consciousness if it is cued by some other thought or perception—some other node in the nearly limitless interconnected web.

The science suggests a method for memorizing information quickly, practiced since classical antiquity, called the method of loci, or, more memorably, the memory palace. The idea is to build associations between random information (like the order of cards in a deck) and a pathway through a memorable place, allowing the memory specialist to retrieve them without incident.

Naming chess concepts serves a similar purpose: it allows the player to more quickly access what were previously discrete, abstract concepts, accelerating pattern recognition and cutting through the infinite tangle of the calculation tree. It’s not surprising to me that so many strong players seem to have pet names and images associated with all kinds of operations on the chessboard. Let’s explore some examples.

There’s a reason that first tactics a chessplayer learns have names like pin, fork, and skewer. Each one evokes an image associated with what is happening on the board: a pinned piece is stuck in place like a butterfly behind glass, a fork can spear two pieces (or veggies) at once, a skewer pokes through one piece to the one behind it. We also have names for more complex and specific tactical operations, some more visually compelling (like the windmill) than others (such as Philidor’s legacy).

My friend Dana Mackenzie created a name for a very cool tactic that is easy to miss: the Hook and Ladder Trick. Rather than try to describe it myself, here’s Dana’s explanation from his long-running chess blog2:

The usual ingredients are:

The queens are attacking each other. Normally, one player (I’ll call them your opponent) has just offered a queen trade.

Your opponent’s queen is protected by a rook on the back rank. Think of the queen as standing on top of a ladder, whose base is held by a rook.

Your rook can play a check on the back rank. This deflects the rook that is holding the base of the ladder, so if he takes your rook then you win his queen.

For the Hook and Ladder to work, either your opponent’s king has to be in a mating net, so that your opponent is forced to take your rook, or else you need to have some other tactic after his king moves out of check. Typically that tactic involves an x-ray attack: either you can simply win his rook (as in this example) or you can trade queens and then win a rook (if your opponent has two rooks still).

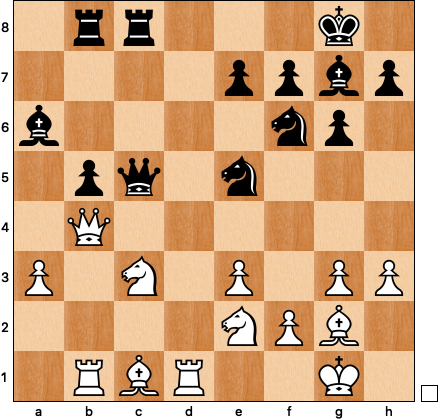

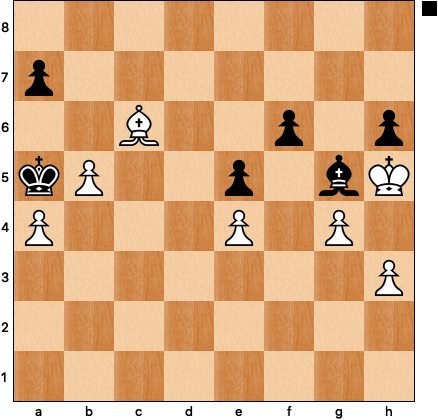

That’s the theory, here’s what it looks like in practice. White to move and win:

Black’s last move was Nd7-e5, which allows 20 Rd8+! Ne8 (or 20 … Rxd8 21 Qxc5) 21 Qxc5 Rxc5 22 Rxb8, winning a rook. Sadly, this is one of the times when I had a name for the tactical idea and still missed it — the Hook and Ladder is an easy blind spot to have! I knew I was missing something and spent twenty minutes before playing the insipid 20 Nd5? and was lucky to win a long game.

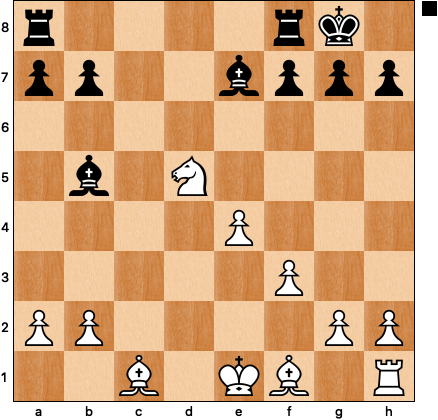

One of my other favorite names for a tactical motif comes from Bobby Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games. The diagram below shows the end of a tactical sequence: Fischer sacrificed a pawn on d5 to break Lombardy’s Maroczy Bind, won an exchange, but appeared to be in some danger after Lombardy’s Nb4-d5, targeting both bishops:

Fischer played 17 … Bh4+!, which he described, in his usual laconic style, as “the scorpion’s sting at the tail-end of the combination.” It’s a perfect name: the bishop stings the black king with an easy to overlook check that isn’t immediately fatal, but foils white’s plans. Indeed, after 18 g3 Bxf1 (as there’s no longer a Be7 falling with check) 19 Rxf1 Bd8 Fischer kept his extra exchange and eventually won the game.

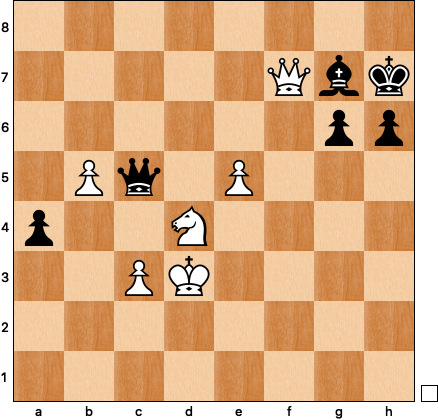

I’ve given names to a variety of tactical operations over the years, some of which have more personal resonance and some of which are more widely applicable. One of the simplest I call the Computer Trick, if only because I fell into this tactic over and over again against my 1990s-era chess computer when I was 11 or 12 years old. Here’s a more recent example:

White would like to play 46 Ne6, but 46 … Qxb5+ is a problem. As is so often the case with tactics, switching the move order makes everything work out: 46 Qxg7+! and black resigned due to 46 … Kxg7 47 Ne6+, winning a piece and the game. That’s the Computer Trick in a nutshell: you sacrifice a rook or queen to set up a knight fork that wins the material back with interest.

After seeing it recommended by a few different strong players, I recently bought a copy of Perfect Your Chess by Volokitin and Grabinsky. It’s a cool book: a variety of chess problems that aren’t entirely tactical in nature. I managed to solve the first one very quickly because I already had a name for it floating around in my head:

White holds the positional trumps, but black struck with 31 … Ne4+! 32 fxe4 dxe4 33 Ne1 e3+! 34 Bxe3 Rxd2+ 35 Bxd2 Re2+ and quickly drew the game.

I call this kind of solution to positional problems “Cutting the Gordian Knot.” Here’s the mythic-historical background:

According to the ancient chronicler Arrian, the impetuous Alexander was instantly “seized with an ardent desire” to untie the Gordian knot. After wrestling with it for a time and finding no success, he stepped back from the mass of gnarled ropes and proclaimed, “It makes no difference how they are loosed.” He then drew his sword and sliced the knot in half with a single stroke.3

“Cutting the Gordian Knot” isn’t a specific tactic but an attitude, a way of expanding one’s options in a bad position. Rather than try to untie the knot slowly/defend passively, the idea involves taking a more aggressive approach to cut through the problems with the sword/tactics.

Naming endgame concepts is also very important. Most players know the Lucena position thanks to the idea of “Building a Bridge.” Similarly, I’m able to remember the Vancura position because of David Pruess’ explanation that he always imagines a crazy old man hunched over a chessboard, inventing this improbable defensive idea. The Vancura defense is just one example of what Dvoretsky calls “Pawn in the Crosshairs,” an evocative image to show the importance of attacking the opponent’s pawns to restrict enemy pieces in the endgame.

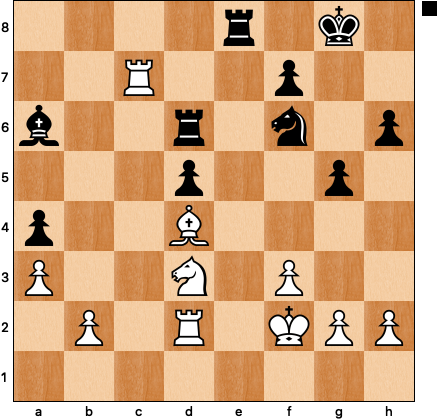

Another example of “Pawn in the Crosshairs” appeared a few boards away from me during round four of the Berkeley Chess Club Championship:

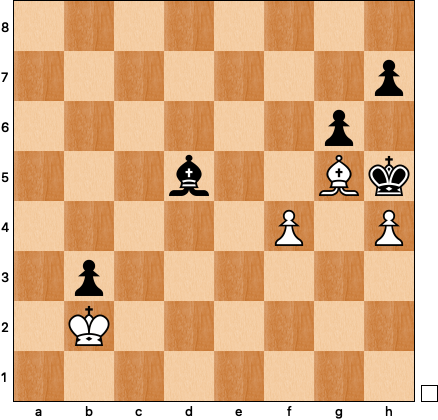

The black king is tied to the queenside, so the bishop must somehow deal with the dangerous white king. Black marked time with 57 … Kb6? and lost after 58 h4 Be3 59 Kg6, but he could have drawn by playing 57 … Be3 (or Bf4 or Bd2, but not Bc1) 58 h4 (58 Kg6 Bg5!) 58 … Bf2, keeping the white pawn in the crosshairs and preventing Kg6.

This defensive idea comes up frequently in opposite-colored bishop endings. One of my teammates missed it and lost a critical game at the US Amateur Team West in February, and it showed up again in the first game of the World Cup finals:

At first it seems like white has nothing to worry about: 48 Kc3 h6 49 Bf6 Kg4 50 Bg7 and white is in time to take on h6, is he not? The problem is 50 … g5! 51 fxg5 h5! and white can’t stop black from taking on h4 with a second passed pawn. Sindarov found the right approach, 48 Bf6! Be6 49 Kc3 h6 50 Bg7, attacking the pawn-h6 before black has time to move his king off h5, and the game was drawn.

I've decided to name this the “Babysitter Bishop.” Our king is off dealing with other problems and the bishop has to hold down half of the board on its own against the dangerous enemy king. It’s always a little surprising to me that it can do so, and hopefully having a name for the idea will help me see it more quickly in my own games.

I could probably list some more, but I’m curious to hear from Lit & Chess readers: do you have any favorite names for tactics or motifs? Share ‘em in the comments!

Sometimes thirty moves deep! From the opening to the endgame, I suppose.

Here’s the link to the original post which has another cool example as well as links to the many other times Dana wrote about the Hook and Ladder Trick over the years.

One of my favorites is Dvoretsky's "pants", where a bishop can't stop two passed pawns if it's stopping them on separate diagonals.

Similar to your Gordian Knot is the "Shankland Rule": if I see a move I want to play, but it doesn't seem to work for some tactical reason, think about what would happen if I played it anyway.