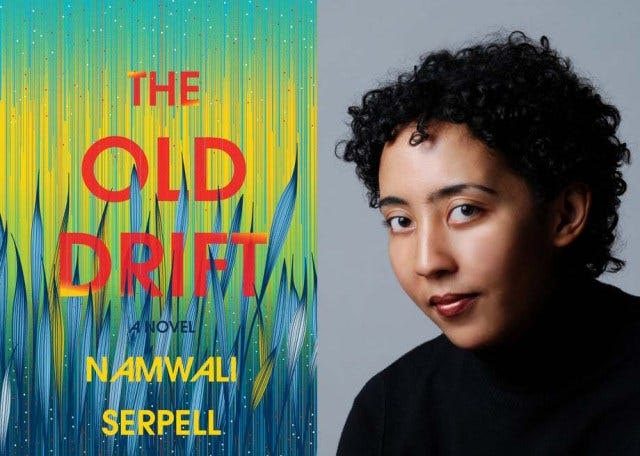

The New York Times released a list of the top 100 books of the 21st century earlier this year, a triumph of crowdsourced list-making, given that the compiled opinions of 500 experts landed three of my favorites in the top ten1. Each book got a short review and a list of other books that you might like if you’d already read it. I’m a big fan of The Savage Detectives2, so the Times’ recommendation that I try The Old Drift, an intergenerational family tree of a novel set in Zambia, caught my eye.

The danger of picking books this way is that the comparison is bound to disappoint. The Old Drift isn’t anything like The Savage Detectives, whose Peter-Pan-like protagonists imbue the narrative with antic energy that never dissipates. The characters of The Old Drift begin this way—we meet each generation in the years of their romantic youth—but they grow steadily more old and broken, their relationships hollow, their dreams deferred, their legacies forgotten.

So much happens in The Old Drift that it’s hard to decide what the novel is actually about. In one generation it’s the story of decolonization and the thrills that accompany revolution: Marxists holding court on university campuses, plans to send Zambian Afronauts into space. A generation later it’s prostitution and infidelity and AIDS3, the naive joy of freedom from colonial rule replaced by the bleak work of just getting by. In the third generation we’ve reached an anti-Black Panther4 future in which the effects of western technology have corroded both civil liberties and the imaginations of those who, in another time or place, might be willing to fight for them.

My initial reading was that technology provides the connective tissue, from the construction of the Kariba Dam in the late 1950s, to the search for an AIDS vaccine, to the microdrones of Serpell’s imagined present and future. These efforts are all moral failures. Even when the technology works, the human cost is too much to bear. Serpell addresses these problems obliquely, through the personal stories of her protagonists, rather than focusing on the thousands displaced by the dam or the millions who have died of AIDS, a choice which centers us on character rather than polemic.

This suggests that we should be looking to the family itself, rather than technology, for the core of the novel’s meaning. Serpell seems quite aware that readers will want to do this, bringing three disconnected branches of the family tree together, first through a car accident and again when a girl falls out of a tree. The car accident I found unfulfilling: if a pair of characters hits another character with a car and leaves him to potentially die, I expect that something dramatic will happen: a reckoning that will change the trajectory of the lives involved. That no such reckoning occurs makes me feel that the connections were written simply to link pieces of plot rather than in the purpose of some bigger theme or idea.

That said, it’s true that in life often nothing dramatic happens: people forget, they rationalize, some of their secrets die with them and are buried. Serpell uses Dr. Livingstone’s obsession with finding the source of the Nile to remind us of the folly of trying to find the source of any and all human behavior in this lovely passage:

Neither Oriental nor Occidental, but accidental is this nation. Would you believe that our godly Scotch doc was searching for the Nile in the wrong spot? As it turns out, there are two Niles — one Blue, one White — which means two sources, and neither one of them is anywhere near here. This sort of thing happens with nations, and tales, and humans, and signs. You go hunting for a source, some ur-word or symbol and suddenly the path splits, cleaved by apostrophe or dash. The tongue forks, speaks in two ways, which in turn fork and fork into a chaos of capillarity. Where you sought an origin, you find a vast babble which is also a silence: a chasm of smoke, thundering. Blind mouth!

That first sentence, the importance of accident, is the missing piece that serves to connect the parts of the story. Human error is present throughout the novel and in both the technological and family tree readings: the many characters, whether they are on the verge or romantic or scientific breakthroughs, are constantly making mistakes. Serpell returns to this idea towards the end of the novel:

This story does have a lesson. Your choice as a human may seem stark: to stay or to go, to stick or strike out, to fix or to try and break free. You limit yourself to two dumb inertias: a state of rest or perpetual motion.

But there is a third way, a moral you stumbled on, thinking it fatal, a flaw. To err is human, you say with great sadness. But we thinful singers give praise! To the drift, the diversion, that motion of motions! Obey the law of the flaw!

As the Gnostic Gospel of Philip opined: ‘The world came about through an error.’ He probably meant God, but for good old Lucretius, this was a matter of matter. When atoms plummet like rain through the world, they deflect — oh, ever so slightly, just enough that their paths divert. From this swerve, called the clinamen, came collision and cluster, both the binding and fleeing of matter. Stephen Hawking once said, ‘Without imperfection, neither you nor I would exist.’ Every small stray opens up a new way, an Eden of forking digressions.

The Old Drift is a remarkable novel in so many ways. Serpell’s prose is both elegant and inventive5. I learned a lot about Zambia without ever feeling like I was getting a history lesson. Many of the set pieces are deeply compelling, most memorably the story of the woman who puts price tags on all the items in her home, and the story of her daughter’s quest to return her father’s ashes to India.

And yet, when I finished the novel, I felt unfulfilled. There’s a theory at work in The Old Drift about what it means to be human that at moments feels profound and at others like it’s searching for profundity. Towards the end of the novel, the third generation of protagonists organizes a protest with an acronym that has no meaning, for a cause that they have not defined. That sums up how I felt about the missing center of The Old Drift: it’s about so many things at once that I think I would have preferred it as a collection of short stories, unburdened by the need to make some greater meaning. Sometimes it’s better to leave dots disconnected.

Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead at #10, Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 at #6, and Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall at #3.

Perhaps criminally underrated at #38.

Which is given the Voldemort treatment and referred to only as “The Virus.”

The novel is self-aware in this regard; one of the characters is briefly nicknamed “Killmonger.”

The two chunks I pulled in this post are narrated by mosquitos, who speak lilting almost-couplets.