My wife and I do the New York Times word games just about every evening. Practice makes perfect, the saying goes, and we’re quite a bit better at all the games since we started1, but our improvement is most notable in Connections, in which the player must lump sixteen words or phrases into four groups of four. Connections is the kind of game in which the links between the words can be painfully difficult to discover at times, but more recently I find that the relationships appear without much difficulty.

I would argue that solving Connections quickly, almost subconsciously, is not dissimilar to good form in chess. At these times I recognize the critical moments quickly and the right variation sometimes appears in my brain fully formed. When I’m in truly excellent form I play without doubt or worry. The double-checking of important variations still occurs, as it must, but it’s relatively quick, part of the wonderful feeling that Mihály Csíkszentmihályi calls “flow.”2

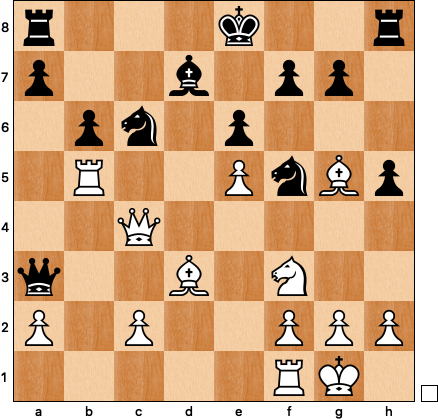

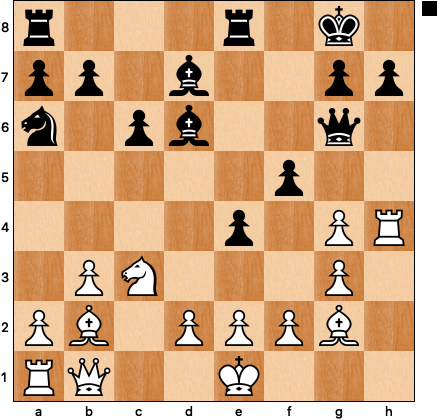

Here’s an example from one of my own games from a number of years ago. Black is clearly in some trouble, but white should be satisfied with nothing short of a knockout blow:

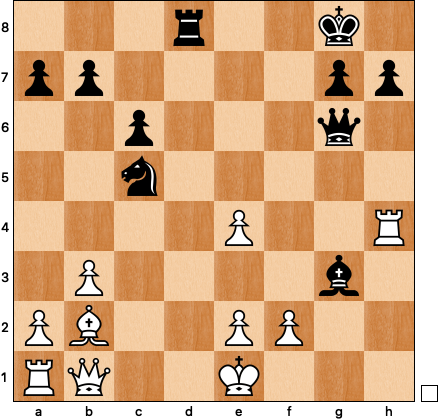

There are a number of tempting options, but I quickly settled on the most incisive, 17 Bxf5!3 It’s not immediately obvious that white should give up this bishop, but the point is that after 17 … exf5 18 Rd1 black’s king is tied to the loose Bd7 and the Bd7 is tied to the loose Nc6. 18 … Na5 loses to 19 Qd5, so my opponent tried 18 … Ne7, running right into 19 Rxd7! Kxd7 20 e6+ fxe6 21 Ne5+ Ke8 22 Qxe6:

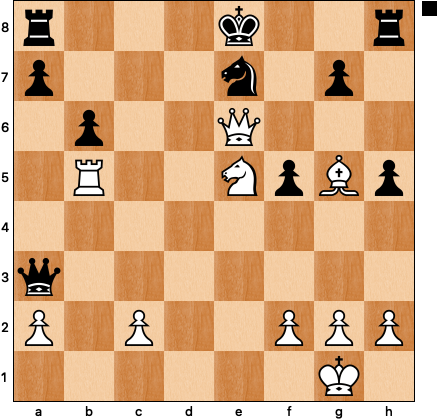

Now mate will come soon, but it’s worth noting that the Bg5 covers black’s mate threat on c1. Awareness of these details is a big part of good form as well; they are the difference between a well-executed tactical sequence and a nasty shock.

Sadly, my games this summer have been more shocking than anything else, and what follows is a recap of form so bad that the only word for it is ugly.

There are two elements of form that tend to be mutually reinforcing for good or evil: seeing variations and making decisions. If your board vision is screwed up, as mine has been off and on this summer, it’s hard to make good decisions simply because you have little faith that what you calculated is correct.

However, it’s also possible to see a lot of critical variations relatively clearly and still make awful choices. Sometimes our intuitive sense is out of concert with our calculations, or the right variation is lost in a tangle of intriguing but unsatisfactory continuations. It’s hard to explain these misses in a post-mortem other than to plead temporary insanity.

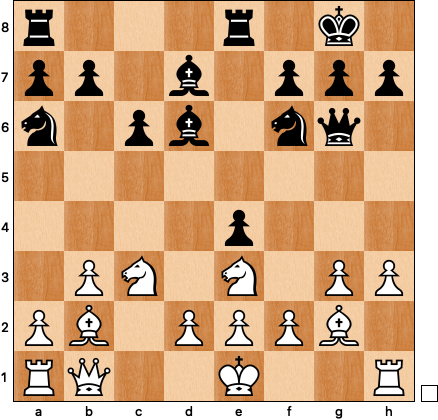

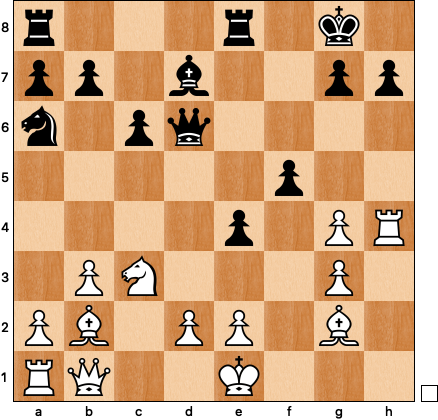

In round six of the Summer Tuesday Night Marathon, with a chance for a good result if I won my last two games, I had the following excellent position with the black pieces:

My opening preparation was, for once, excellent and black has a substantial advantage. Unfortunately, good opening preparation often conceals bad form: just because you can remember something doesn’t mean that you’re going to make good middlegame decisions. And I was caught off guard by white’s attempt to reduce the pressure, 14 Ng4, a move that under normal circumstances I should have anticipated.

I played 14 … Nxg4 15 hxg4 and now simply 15 … Bxg4 16 Bxe4 f5 would have increased black’s advantage:

I lazily decided that white can play Bg2 and e3 and survive for a while, discounting the fact that soon all of black’s pieces will be in the attack (Nc5, Rad8), while white’s queenside jumble is of no use at all. This unsubstantiated feeling of “I deserve better” is a sign of bad decision-making and bad form — it’s dangerous to think about the evaluation outside of the context of specific positions and variations on the board.

After some thought, I decided that I had found a solution: 15 … f5, hoping that white would trade on f5, bringing my bishop into the game with the threat of e4-e3. Instead he played a more cunning move, 16 Rh4, and I had another long think:

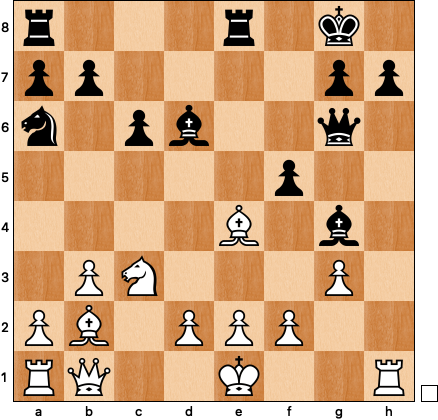

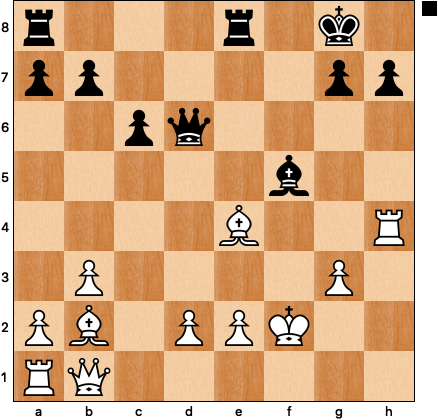

The position has sharpened thanks to white’s plan of rounding up the e4-pawn. Black is still much better, but there are suddenly bad moves as well as good ones, such as 16 … Nc5 17 b4 Nd3+ (an unsound sacrifice) and 16 … fxg4 17 Bxe4 (with a disaster looming on h7). But 16 … Rad8 is sensible, and if white “wins” a pawn with 17 gxf5 Bxf5 18 Bxe4 Rxe4! 19 Nxe4 Nc5 20 d3 Bxe4 21 dxe4 Bxg3! is crushing:

Instead, totally unmoored from reality by my bad form, I decided to play the insane 16 … Bxg3? 17 fxg3 Qd6:

This gets high marks for creativity, I suppose, but low marks for accuracy, since white can just play 18 Kf2 and none of black’s attacking continuations work out, not Qxd2 nor Qd4+ nor fxg4 nor the move I played 18 … Nc5.4 The fact that I have to spend a tempo getting the knight into the game and another tempo to bring the rook to the f-file should have been a big clue that sacrificing the bishop was a losing blunder.

What moves this game from bad form to ugly is what happened next. My opponent’s technique was shaky, and he gifted me one more chance:

21 … Rxe4! 22 Rxe4 Rf8! is very strong, and now white has to find 23 Kg2 just to avoid losing. I hate to say it, but this idea didn’t even appear on my radar — if I’d seen it the craziness of Bxg3 could almost be forgiven. Instead I played 21 … Qxd2?, a huge miscalculation of every possible reasonable variation for white. Indeed, 22 Qd3, 22 Bxf5, and my opponent’s choice, 22 Bc1, all win.

It’s easy to engage in catastrophic thinking when you’ve lost 30+ rating points5 over a nine game stretch in ways that were hardly imaginable when you were ten years younger. I told a friend who had recently dropped to his rating floor that I might be an expert in a master’s body. At least that’s what my level of play in 2025 would indicate.

The antidote to this kind of thinking is to go back through the ol’ tournament history and find that such dips and drops are pretty normal. After I got up to the mid-2300s for the first time in 2010 I immediate dropped 37 rating points over my next two tournaments, 13 games in all. In fact, I didn’t stop falling until I was back in the mid-2200s a year later, convinced that I was never getting over 2300 again. In late 2003 I hit a new high of 2241; a few months later I was surprised to find myself back under 2200. And most impressively, way back in 1996 I lost every game I played in a weekend swiss, dropping more than 80 points off my shiny new 1800 rating.

The moral of the story is that form, like rating, comes and goes, and we only have so much control over it. I’d like to play well in the near future, but if I don’t it’s not the end of the world — the experience of trying to find that elusive flow is had to resist.

Next up I’ll be looking over a game or two from the Sinquefield Cup, where Pragg is in great form and Abdusattorov … not so much. Thanks for reading.

And it’s quite an advantage to work on them together.

“We have called this state the flow experience, because this is the term many of the people we interviewed had used in their descriptions of how it felt to be in top form: ‘It was like floating,’ ‘I was carried on by the flow.’” — Csikszentmihályi, Flow, 1990

17 Rd1 should be similar, but 17 Be4 and 17 Rb3 are not as strong.

My friend Peter Newhall calls this sort of thing “hope chess” — playing a risky move with the hope that something will emerge later on. It usually doesn’t.

Everything that follows is USCF ratings; I’d rather not even look at the damage I’ve done to my FIDE rating.

Wow. I'm really glad I read this one! Being in the footnotes means I've hit the big time! Maybe I should start playing chess again and drop dozens of rating points too :).

Timely as I just blew today’s Connections for the first time in weeks.