How does one know that a game of chess is brilliant? Like the famous Supreme Court definition of obscenity, I tend to know a brilliant game when I see one, and I certainly suspected1 that Rapport’s victory over Praggnanandhaa in round six of the Uzchess Cup was special when I first played over it at home.

I wasn’t the only one. Colin McGourty, writing for chess.com, called it “a candidate for game of the year.” Dennis Monokroussos concurred on his Substack, writing that “Rapport played brilliantly.” Rafael Leitao opened his annotations by calling it “one of the best games in recent memory.” Anish Giri said that it reminded him of “Kasparov games I was admiring as a kid.” Kasparov, not to be outdone, quoted The Princess Bride. Rapport himself said that when playing the King’s Indian, you “dream of this kind of game.”

Confirmation via the crowd is nice, but it doesn’t exactly answer the opening question. When I annotate my own games I have no difficulty adding question marks — bad moves tend to make themselves known because they change the objective evaluation of the position for the worse. Brilliant moves can only challenge the subjective, human evaluation of the position — after all, the brilliant move was always there to be played, someone just had to arrive at the position in question and play it. So much of what makes a move or a game great is in the eye of the beholder: if I like flashy sacrifices I might add a “!” or even a “!!” to Bxh7+, even if it’s more pattern-recognition than brilliance, whereas a different annotator might reserve their praise for a well-timed pawn break or the redeployment of a misplaced piece.

Here’s another way of thinking about the definition of brilliancy. I was recently rereading Dvoretsky and Yusupov’s Attack and Defense2 and came across the following insight:

Traditionally, chess players are classed as combinative or positional. At one time it was relatively simple to categorize them on these lines, but today things are different — there are hardly any purely positional or purely combinative players left. In any case, this classification refers only to the outward manner of play, not to the underlying qualities of thought. It gives you too little to go on when it comes to choosing the form and content of a training course suited to a particular player.

To me it seems more helpful to categorize players according to their predominant style of thinking, their characteristic approach to taking decisions — the intuitive or the logical.

Dvoretsky goes on to define the strengths and weaknesses of each type, explaining that intuitive players3 “have a delicate feel for the slightest nuances of a position” but “are none too fond of working out variations. On the other hand, logical types4 “conceive profound plans” and “think in a disciplined manner” but can “sometimes prove too single-minded.”

The truly brilliant game has to operate across this dichotomy. The winner must conceive of something beyond the dictates of logic, a difficult and complex idea coaxed from the intuitive depths. However, having embarked upon this idea, the player must pivot to the “disciplined manner” and bring the game to a satisfactory conclusion without lapses or errors of calculation.

It’s the rare game that displays both of these attributes, but Rapport’s brilliancy is one of them. Let’s take a closer look.

The Intuitive Phase: Taking a Step Off the Ledge

For my purposes, the action begins on move 15, but here’s a link to the entire game. We’ve got a typical King’s Indian structure with some intriguing specific details: white’s Nb5 is stranded, the a-file is open, black’s b-pawns are potentially weak, and black has the unopposed dark-squared bishop:

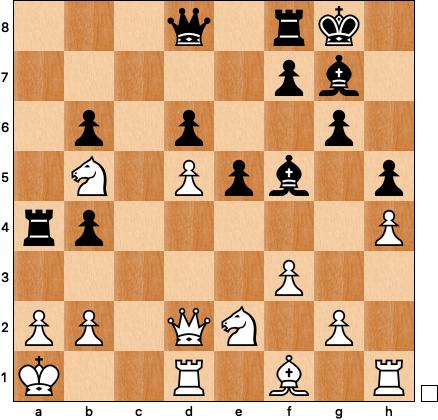

Rapport played 15 … Nxd5, sending the game into the depths of Mikhail Tal’s metaphorical forest5. Pragg replied more or less instantly (as 16 Qxd5 is catastrophic), and the game continued 16 exd5 Bf5+ 17 Ka1. I would generally only be willing to play this way if 17 … Rxa2+ 18 Kxa2 Qa8+ was mate, but it’s not, so Rapport played 17 … Ra4! and Praggnandhaa had his first serious think:

The speed at which the players arrived at this position suggests that both were aware of the Nxd5 idea beforehand and considered the position worth playing for their preferred side. Is Rapport’s knowledge of the engine’s endorsement a death blow to the idea that he has produced something both intuitive and brilliant? Perhaps a little, but the knowledge that a position is objectively playable is far different from knowing how to actually play the position. Take it from me — I spent some hours this week trying to understand why white can’t just play 18 b36.

I began by rejecting 18 … Ra5 19 Qxb4 Qa8 20 a4 as ineffective. White gets the a2 square for his king and he only needs a couple more moves to complete his development. 18 … e4+ looked like a promising alternative. White has to play 19 Ned47 and then 19 … e3 20 Qxe3 deflects the queen away from b4 leaving black enough time for 20 … Ra5:

I was working on this position with another of Dvoretsky’s ideas about intuition in mind:

For instance, it is certain that after sizing up some variations Mikhail Tal would quite quickly have decided that the sacrifice was promising (that is the point — not provably correct, but promising) and that he ought to go in for it. Or, instead, he would have assessed its consequences as favorable to Black, and played differently.

Dvoretsky writes this as alternative to the method of the logical player who might go crazy (and would definitely land in time trouble) trying to calculate all the variations in search of the objective truth. In my notes I decided that this was the variation that showed promise. I wrote “maybe that’s all you need to see to make the decision to sacrifice on d5” and looked at a single variation to confirm my belief that white could not untangle: 21 Bd3 Qa8 22 Rd2 Re8 (deflecting the overloaded queen) 23 Qf2 Bxd3 24 Rxd3 Rxb5 and black should win.

Unfortunately, as it so often happens, this analysis is no good; white can defend and consolidate his extra piece with something like 21 a4, a move I considered after white takes on b4 but not when black can capture en passant. Sadly, the black pawn on a3 provides some needed shielding for white’s king.

So what’s the right answer? Consider the position after 18 b3 Ra5 19 Qxb4 once again:

This is the position I rejected because of 18 … Qa8 19 a4, but the computer says no problem, you just keep giving up material: 18 … Rxb5! 19 Qxb5 Qc7. White has an extra rook spectating from h1 while in the meantime e5-e4+ is going to be a crusher. Here’s a funny computer line: 20 Qc6 Qa7 21 Ng3 Ra8 22 Qa4 Qxa4! (trading queens to go into the rook down ending) 23 bxa4 Bc2:

White can’t both save the rook and hold off the check(mate) on the long diagonal: for instance 24 Rb1 e4+ 25 Rb2 Rxa4 and there’s no good way to stop Rb4 next.

These variations, just a few of the many hidden just off-stage, demonstrate to me that Rapport’s sacrifice is an act of intuition, in the difficulty and risk that black takes on as much as the concept itself. Black’s attack is dangerous, but he’s balancing the whole way on the cliff’s edge, and any misstep could prove fatal.

The Logical Phase: Calculation and Technique

Given the difficulty of the position, it’s not surprising that Praggnanandhaa made some mistakes; what’s remarkable is the perfection of Rapport’s play8. Here’s the next critical moment on move 21:

Black has just opened the long diagonal with e5-e4; I wondered why white couldn’t simply play 21 fxe4. At first I assumed that the reason was 21 … Bg4, picking up the exchange, but the position after 22 Qd3 Bxd1 23 Rxd1 isn’t all that promising. After all, black sacrificed a piece to get here, so winning back the exchange doesn’t recoup his entire investment.

Then I found the right solution — 21 … b3! 22 Bxb3 Rxe4 23 Qf1 Rb4 — but here I abandoned the variation prematurely, not realizing that 24 Na3 loses to 24 … Qa7:

Before proceeded further, let’s compare this position to Leitao’s instructive drawing line from his analysis for chess.com, starting from the previous diagram: 21 Rhe1! exf3 22 gxf3 b3! 23 Bxb3 Rb4 24 Na3 Qa7 25 Nb5 Qd7 26 Na3 Qa7. That’s funny, it’s the same position as the one above, just with the Qf1 on e2 and the Pg2 on f3. What gives?

The point is that if white plays 25 Nb5 in the diagrammed position, black has 25 … Rxc1+! 26 Rxc1 Rxb3! 27 Nxa7 Bxb2# — and so white is only safe in the variation with his queen on e2. It’s a tiny subtlety that makes all the difference.

Pragg’s 21 Bb3 cleverly cut out the b4-b3 idea but failed to another impressive display of tactical acumen from the mind of Rapport: 21 … exf3 22 gxf3 Ra5 23 Bc4:

Praggnanandhaa was undoubtedly hoping for 23 … Rxc4 24 Qxc4 Qxb5 25 Qxb5 Rxb5 26 Nb3 when white has chances to hold thanks to black’s awkwardly placed rook. But Rapport was ready with 23 … Bc2!, an amazing piece of chess geometry — the bishop is on its way to a4!9

That was the last great move that Rapport had to find, but he carried out the technical portion of the game with aplomb and Pragg threw in the towel after move 37.

When I was much younger I bought a book of Kasparov’s games in the King’s Indian Defense that were mostly annotated in the language of Chess Informant — no words or narrative, just symbols. I found these games to be impenetrable until my rating crossed 2000, and even then I often didn't understand how Kasparov managed to play with what felt like such reckless abandon, how he came up with moves that prioritized the initiative over material concerns. This game is a throwback, an incredible struggle that is both logical and mind-bogglingly complicated at the same time. It’s a brilliant game because Rapport steered with such a steady hand, through both the irrational and technical phases, and because Praggnanandhaa put up a hell of a fight10. I hope that these annotations were helpful in making sense of some of its secrets.

I had the eval bar turned off, so I wasn’t initially sure how sound Rapport’s play had been.

It’s a wonderful book that covers far more topics that just attack and defense.

According to Dvorestky, this group includes Capablanca, Tal, Petrosian, and Karpov.

Kasparov, Botvinnik, Rubenstein, and I would add Fischer.

“You must take your opponent into a deep, dark forest where 2 + 2 = 5, and the way out is only wide enough for one.”

I should have also spent more time on 18 Ng3, which I rejected due to 18 … Qa8, but 19 Bc4 is still very complicated.

But not according to the chess.com machine, which rated his accuracy at 98.6, yet another example of the utter uselessness of the accuracy score.

Since 24 Qxc2 Qxb5! 25 Bxb5 Rxc2 is crushing.

Yet again, this blog has chosen to focus on the loss of the winner of the tournament — and Pragg’s been winning everything in sight lately.

As a sub-2000 scrub, I found this review of Richie's Immortal helped me to better understand what is "brilliant" about it. I'm curious, do you think that the kinds of sacrifices made by an intuitive player (e.g. Tal) are qualitatively different from those made by a logician (e.g. Kasparov)?