This is the second in a series about the best and worst world championship matches of the 21st century. Here’s a link to the first article, which describes my methodology.

#12: Vishy Anand-Boris Gelfand, 2012 (10 points)

Legitimacy (12th place, 1 point)

Vishy Anand entered the 2012 match as a legitimate champion, having defeated his two closest rivals (Vladimir Kramnik and Veselin Topalov) in the previous two championship matches. At the time of the 2012 match, only three players were rated above him: Magnus Carlsen, Levon Aronian, and Kramnik.

So, with apologies to Boris Gelfand, why didn’t we get a match between Anand and any of these three worthy opponents? The problems began when Carlsen dropped out of the Candidate’s cycle, annoyed that FIDE had changed the qualification format to a series of mini-matches. He was replaced by Alexander Grischuk, who decided that his best chance to qualify was to try to draw every classical game and then win in the rapid tiebreaks. To accomplish this, he offered quick draws with the white pieces and then held on grimly with the black pieces before winning the rapids, a strategy he executed to perfection against first Aronian and then Kramnik. Having cleared the field, he finally succumbed with black in the last game of his match against Gelfand, who had relatively easy path, having beaten Mamedyarov and then Kamsky.

Ranked only twentieth in the world at the time of the match, Gelfand would have been comparable to Max Euwe if he had won; even in a losing effort he is the most improbable challenger of the 21st century. The chess world is worse off for missing out on a 2012 Anand-Aronian match, or even Anand-Carlsen a year earlier when the pairing might have been more competitive1.

Excitement (6th place, 7 points)

Excitement is the one area where this match shines emits a dull glow. It went to tiebreaks! Anand was behind (briefly)! Then he caught up!

Don’t let the exclamation marks fool you: this was one of the least exciting matches to make it to tiebreaks. When the champion gets behind there’s usually a period of tension in which the spectators wonder if will he be able to mount a comeback. In this case, the question was answered 17 moves later, when Gelfand lost the shortest decisive game in world championship history. The two mini-peaks in this match (games 7-9 in regulation and then tiebreak games 2-4) sum up the problem: neither player was in great form, and so rather than a steady increase in tension, many of the critical games fizzled out. Despite getting some good positions, neither player could put the other away, and it’s fair to say that Gelfand lost the match more than Anand won it in the end.

Chess Content (12th place, 1 point)

You can make the argument that while there are some other matches that are almost as low in the legitimacy and legacy categories, no other match for the world championship saw such dull and uninspired chess. The first six games were drawn, and one could be excused if they thought that Gelfand had been infected by Grischuk’sn match strategy, as he played the same tepid line with white against the Semi-Slav over and over again.

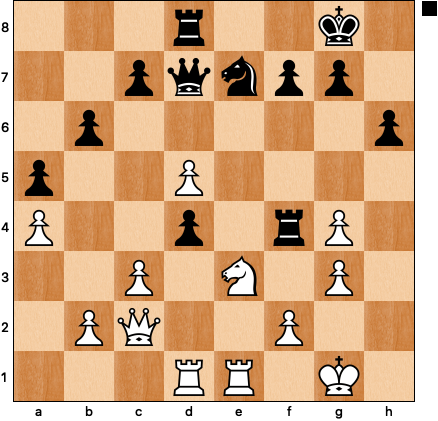

There’s only one position that really comes to mind when I think of this match:

Gelfand had played rather strangely in the opening, but his choice to sacrifice his h5 knight to “win” white’s king rook was disastrous. Anand finished him off with 17 Qf2! and there was no way out for the black queen.

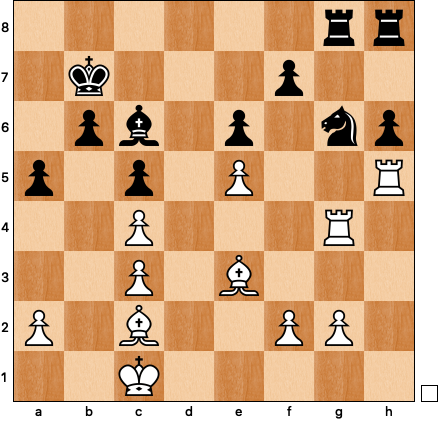

And the best game of the match? Well, here’s a lovely position for you:

Anand, whose mastery of the black side of the Semi-Slav was well established in his 2008 victory over Kramnik, played the inspired 15 … Bc5! The point is that after 16 dxc5 Nxc5 17 Be2 Qd4+ 18 Kh1 Nf2+ 19 Rxf2 Qxf2 white is getting mated. White struggled on with 16 Be2 only to be hit with an even more powerful shot from Anand: 16 … Nde5! with the following point in mind: 17 fxe5 Qxd4+ 18 Kh1 Qg1+ 19 Rxg1 Nf2#.

What’s that? This game isn’t from the 2012 Anand-Gelfand match at all? Good catch: this is the 2013 brilliancy Aronian-Anand, included here as a passive-aggressive reminder that Anand-Gelfand produced no great struggles worthy of the world championship and that instead of an alternate reality Anand-Aronian match, we got one great game.

Legacy (12th place, 1 point)

It’s time to go full Frank Capra and ask, in the tradition of It’s a Wonderful Life, what the world would be like if the Anand-Gelfand match had never happened. As far as I’m concerned, nothing would be different at all. Anand-Carlsen still happens in 2013, Carlsen wins handily, the flap of butterfly wings is hardly noticed by the chess world as it wanders down this alternate/not-so-alternate reality.

What did we learn from this match? It was a sign that the Anand of the 2008 and 2010 matches was gone—that guy would have destroyed Gelfand without needing tiebreaks. The brief flurries in the Sveshnikov and Rossolimo Sicilians foreshadowed their appearance in the 2018 Carlsen-Caruana match. But that’s about it: this was the one match that I flat out forgot as I made a list of all twelve matches of 21st century when beginning this project. Will we ever again see two players in their forties compete for the title? Probably not, and that’s a good thing.

#11: Magnus Carlsen-Ian Nepomniachtchi, 2021 (12 points)

Legitimacy (7th place, 6 points)

Despite his many complaints about the format, Carlsen adds legitimacy to every match he played. He’s been number one in the world for so long that it’s hard to remember who occupied the top spot before him2.

Nepomniachtchi was a worthy challenger, number four in the world at the time of the match. He finished ahead of his rating rivals Caruana and Ding at the COVID interrupted 2020-21 candidates. Even so, I rank him somewhat below Caruana and Topalov as the most legitimate losers of world championship matches this century. A Caruana victory in 2018 or a Topalov victory in either 2006 or 2010 would have been less surprising than Nepo bringing Carlsen’s world championship career to an end through defeat rather than ennui.

Excitement (12th place, 1 point)

If you graphed excitement level over time, you’d get a slow buildup over the first five games, a sharp peak in the middle, and then a precipitous descent down the far slope. We’re really talking about two distinct matches, the first decided only by a marathon Carlsen grind in game six, the second a bloodbath, as Nepo went on tilt and could not right himself in time.

Given the tensions of the first half, it might seen unfair to rank this match at the very bottom, but one player mercilessly crushing the other just isn’t a compelling viewing experience. Carlsen’s winning margin, +4, is the highest of any 21st century match. If you loved Kasparov-Short, 1993, this match is for you. For everybody else, there are a lot more exciting matches out there.

Chess Content (11th place, 2 points)

I actually changed the chess content rubric specifically because of this match. Initially the lowest score for a decisive game was three points, but this scoring system gave too much credit to the games decided by Nepo’s blunders: eight, nine, and eleven. Here’s the an example of the kind of chess he was playing in the second half of the match:

Nepo had just decided to poke at the black rook with g2-g3, a move that proved to be his undoing. Carlsen didn’t have to be asked twice to sacrifice the exchange: 23 … dxe3! 24 gxf4 Qxg4+ 25 Kf1 Qh3+ 26 Kg1 Nf5 and white could already resign—he’s losing the exchange back soon and will be down some key pawns with an exposed king—but Nepo played on another twenty moves. It was, technically speaking, last game of the match, after all.

The last competitive moment of the match was game six, and what a game it was: at 136 moves, the longest game in world championship history. Nepo was still playing excellent chess, grabbed the initiative, and then raised the tension by trading his rooks for Carlsen’s queen. Both players missed serious chances around the first time control; the game remained sharp and balanced. Carlsen sacrificed the exchange for some pawns and went to work trying to grind Nepo into dust: ten moves, twenty moves, eventually fifty moves of rook and knight (and two extra pawns) against the Nepo’s lone queen. The position was theoretically drawn but practically speaking impossible to hold: Carlsen would have happily tortured Nepo for another fifty moves if he had to.

To do any meaningful analysis of this game would a) take me another week, b) exceed the space limits for this post, and c) cover annotation ground that has already been done better by others. Here’s a link that (if you scroll far enough) provides some amusing annotations from the mind of Sam Shankland, who was on a flight with spotty wifi as game six was being played. His many reconnections to the internet demonstrate the game’s epic length; unfortunately it took Nepo past a place from which he could recover.

Legacy (10th place, 3 points)

Should Carlsen’s final match3 have a higher legacy ranking? I suppose it could have if it had been more exciting. I imagine we’ll remember Carlsen-Caruana far better, as there’s nothing beyond game six of this match that lingers in my memory. The Carlsen era didn't really end with this match; it ended months later when he finally decided not to defend his title. Alternatively, it isn’t over at all, as we’re still likely years away from his number one spot on the rating list falling to one of his competitors.

#10 Magnus Carlsen-Vishy Anand, 2014 (18 points)

Legitimacy (8th place, 5 points)

Anand’s return as a challenger in 2014 was as impressive as it was unexpected. In 2013 he put up little resistance against Carlsen. A year later he earned a rematch by winning the Candidate’s tournament with an undefeated +3, the sort of thing that hadn’t been done since the Kasparov-Karpov era. That was a simpler time, as the two Soviet champions were so clearly the best players on the planet that no one begrudged their repeated title matches, even when they failed to cap the number of games ahead of time.

Given his status as former world champion, it feels rude to describe Anand’s return as somehow illegitimate. But it’s hard to shake the feeling that (much like Gelfand two years and two matches earlier) he was taking a spot that could have been better occupied by Aronian or Caruana. Anand finished well ahead of his Armenian rival at the 2014 Candidate’s, but Caruana wasn’t even in the field, a case study in how the snail’s pace of the qualification cycle managed to skip past a guy who—how to put this delicately—WON SEVEN STRAIGHT GAMES AT THE 2014 SINQUEFIELD CUP, A RECORD THAT STILL STANDS TODAY.

Excitement (7th place, 6 points)

While Anand lost a second time to Carlsen, he managed to put up a better showing than in 2013 and had a chance to make the champ sweat a little. Like most of the matches on the bottom half of the chart, this one doesn’t have a clear peak of high tension and great games, but the fact that both players won games in the first half and that Anand had a golden opportunity to win game six injected some much needed uncertainty into the contest.

Anand’s choice to continue to play the Berlin as time was running out was a baffling decision that weakened the case for this match to break into the top six in this category. He wasn’t getting much with white, his final attempt to play the Berlin for a win backfired, and the match ended rather suddenly.

Chess Content (8th place, 5 points)

The chess in this match proved to be … pretty OK? Carlsen’s win in game two was an nice example of his positional style in the middlegame: just keep adding pressure until someone cracks. Anand broke through with an even more impressive win in game three, part of a pattern of the pressure he put on Carlsen with the white pieces throughout the first half of the match.

After Carlsen grabbed the lead in game six, the content of the games declined, most notably in the quick Berlin draw of game nine. But in his final game with the white pieces, Carlsen decided to actually play instead of making a draw:

Anand found an inspired way to complicate the position: 23 … b5! The point is that both 24 axb5? a4! and 24 cxb5?! Bg7 with the idea of Bxf6 and Bxb3 are better for black. The game continued 24 Bc3 bxa4 25 bxa4 Kc6 26 Kf3 Rdb8 27 Ke4, when Anand gave it one last shot:

He could have continued with 27 … Rb3 but instead invoked the spirit of Petrosian with 27 … Rb4, an inspired idea that doesn’t work out tactically. Carlsen’s winning method was instructive: 28 Bxb4 cxb4 29 Nh5. The point is to play f4 and then recapture twice with knights, ultimately dislodging or taking black’s best remaining piece, the Be6. A dozen or so moves later and the match was over.

Legacy (11th place, 2 points)

Sequels are only occasionally better than the originals4, and despite the better quality of chess in comparison to the 2013 match, Carlsen-Anand 2014 is going to be remembered primarily for one thing:

Carlsen had been putting on a clinic in why strong GMs shouldn’t risk the Kan Sicilian and why doubled pawns don’t always matter as much as a space advantage. But he picked the wrong square for his king: 26 Kd2?, allowing black to pick up a couple pawns with 26 … Nxe5! 27 Rxg8 Nxc4+ 28 Kd3 Nb2+. Anand missed the chance, played 26 … a4?, and Carlsen won without further incident.

Ultimately, this match is a kind B-sides affair, overshadowed by its predecessor, that was more interesting than I remembered but did little to change to course of chess history.

It’s sacrilegious to bypass the reigning champ, but Carlsen-Aronian would have also been a great match.

Anand? Maybe Topalov?

Presumably … but how fun would a Carlsen return be right as one or more of the Indian teenagers are getting comfortable in on the chess throne?

The Empire Strikes Back, for example.

It's true that people like the drama of contests to be eligible to play for the World Championship. Throw a bunch of candidates into the Coliseum and get them to fight bears, lions and each other. The last one standing gets his chance at the title. :)

I was a teenager when Karpov was still World Champion, and I enjoyed the legendary matches he had with Kasparov. Throughout the 80s and for most of the 90s it was a given that the best player in the world was also World Champion, and I got used to that.

These days, the World Champion thing feels rather flat, like a glass of Coke which has been sitting too long. But a new era could be around the corner.

Great review, Andy. I think the title of World Champion has lost prestige in recent years. As you say, those who get to play for the title are not necessarily the best in the world. That trend has been exarcebated by Carlsen pulling out and by Ding Liren's tenure, which has been disastrous.

Maybe it would be better and simpler to automatically have the match every three years between the two highest-rated players. At the moment that would be Nos. 2 and 3 (Caruana and Nakamura) since Carlsen is not interested.