The main story of the 4th Menorca Open was the triumphant return of Vasyl Ivanchuk, one of my favorite players and the source of one of the great chess stories of the year. If you haven’t yet read Kostya Kavutskiy’s account of analyzing with Ivanchuk in Reykjavik you should stop reading this and just click the link instead. It’s great stuff, both as a narrative of a once in a lifetime experience and as a guide to chess improvement.

If you’re still here, I’m going to focus on the play of Sam Shankland, the strongest player I know best, whose games I always follow with great interest. Sam has had trouble finding his peak form over the past year or two, and I doubt that he was particularly happy with his play in Menorca. He finished among the leaders with 7/9, but he had to play catch up after a tough 3/5 start. He didn’t end up facing anyone rated over 2500, so despite a +5 score he lost a few rating points.

I found his tournament interesting in a few ways: first because many of his opponents were closer to my rating and playing strength. These are the kinds of players I have trouble beating, and watching a strong GM dispatch them is always instructive. Second, it’s interesting to see how someone like Sam manages to persevere despite not being in form. And finally, many of Sam’s games showed his skill with passed pawns in the endgame as if he were composing variations on a theme; that’s what I’ll focus on here.

Round 1: Creating a Material Imbalance

This is the scenario you dread if you’re one of the top seeds in the first couple rounds. You’ve got about 500 rating points on your opponent, but it’s hard to win when they play solidly, avoid imbalances, and trade pieces whenever possible. White is about 90% of the way to his goal of taking a half-point off a strong GM:

The problem is that his position is still a little uncomfortable. Take a few minutes and consider what you would play with white — it’s not so easy to extinguish black’s initiative. I considered 40 f3 Nc4 41 Re1 Kg7 42 Re2 Ra3 43 Kf2, but now 43 … Kh6! 44 e4 g5 45 Nh3 leaves white’s knight very passive. Alternatively, 40 Nd3 Ng4 41 e4 Kg7 42 Rb1 Kf6 43 Rb2 and black can keep playing for a long time if he moves his rook or can try to eke out a win in the knight endgame.

White played 40 Ke1 with Rd2 in mind, but this played right into Sam’s hands: 40 … Ng4 41 Nd3 Nxe3! 42 fxe3 Rxg2 and once the g3 pawn falls next move he has three pawns for the piece.

The new material situation doesn’t immediately affect the outcome, but it must have had a huge psychological effect on the players. White had been assiduously avoiding any sort of imbalance and was probably deflated to find himself in new and difficult circumstances. Black was likely elated to have a chance at winning what had previously been a dead drawn position.

About ten moves later there was another turning point:

White’s position is unpleasant, as his knight is frozen in defense of the e5 pawn and his rook needs to remain on its active post. However, it’s also hard to see how black makes progress, so Sam decided to trade rooks and was rewarded with the first and only big mistake of the game: 51 … Rd5 52 Rxd5 exd5 53 Nb4 d4 54 e6? fxe6 55 Nc6:

If black plays 55 … d3? 56 Ne5+ is drawn. White could have played for this position by playing 54 Nc6! first and only after 54 … d3 55 e6!1 Sam noticed the move order mistake and found the only winning variation, 55 … e5! 56 Nxe5+ Kf5 57 Nf3 d3. The point is that the black pawns are too advanced and far apart from each other for the white knight and king to stop.

Round 2: The King is a Fighting Piece

Sam got into trouble in a sharp middlegame in the second round and bailed out into an ending down a rook for a ton of pawns. These kinds of material imbalances are brutally difficult to figure out over the board. The evaluation is based on very precise calculation, where one missed nuance can flip the game entirely:

It feels like black must be better, and indeed he is. The problem is that proving the advantage requires a further sharpening of the position rather than the intuitive plan of blockading and rounding up the b-pawns. The winning line is 39 … Nh42 with the threat of Rf3+ and Rf4. With best play — 40 Rc7 Rf3+ 41 Kd2! Rxe4! 42 b7 Rxf2+ 43 Kd3 Rb4 44 Rc8+ Kg7 45 b8=Q Rxb8 46 Rxb8 — we reach this simplified position:

Black gave up a rook for the advanced b-pawn, but he got a lot in exchange. White is running low on pawns, and his most dangerous passer is off the board. Black has all the chances, and while it’s not a sure win, it’s much better than the position black reached in the game after 39 … Rff8? 40 Rc7 Re7 41 Rxe7! Nxe7 42 b7 Nxd5+ 43 Kd4 Ne7 44 Nxd6 Nc6+ 45 Kc5 Nb8:

Superficially, it may look like black has made significant progress — the b-pawn is blockaded, the active white rook has been exchanged, and soon there will be only three white pawns for the rook — but white’s active king more than makes up the difference. The first b-pawn cost black his knight, the second his rook, and in the end he had to scramble to hold the draw.

Round 3: Distractions and Disharmony

Sam was on the ropes with the white pieces for the second straight round, a sure sign of bad form, but he managed to confuse matters and reach this very sharp position:

Black has a dangerous passed d-pawn that he is hoping will hold the balance against the connected white passers on the queenside and potential attacks against his open king. There are some interesting variations that I won’t spend too much time on here: 33 Ng4 d2 34 Nh6+ is interesting, as is 33 Qe6+ Kg7 34 Qe5+ (hoping for 34 … Qf6? 35 b7!). Both are complicated but apparently equal according to the machine.

Sam chose a third option, 33 Nf3, still equal but more likely to keep the game going. His opponent erred immediately: 33 … Rb8? (better was 33 … Qd7!, but not 33 … d2? 34 Nxd2 Qxd2 35 b7) 34 c5 Rb7? 35 c6! Rxb6 36 c7! Qc8:

Notice how nicely the c7-pawn has jumbled up black’s pieces. Nothing is defended, which means that after 37 Qg5+ black cannot play 37 … Rg6 38 Qd8+. The problem is that 37 … Kf7 38 Ne5+ is also curtains, as 38 … Ke6 39 Qg4+ picks up the queen.

Round 9: Two Passers are Better Than One

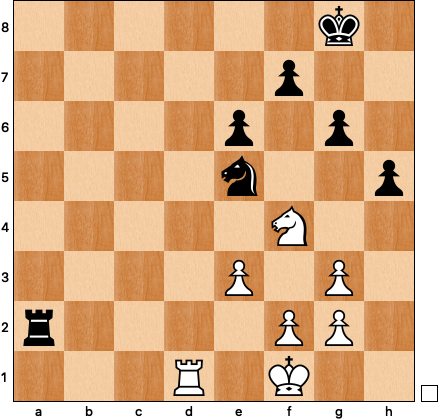

After a draw and a loss, Sam’s play improved in the second half of the tournament. He won in the sixth round in his typical style, taking over the position, winning a couple pawns, and grinding down his opponent. The return to his strengths combined with better positions out of the opening brought him renewed success, but there was one more brief allusion to the power of the passed pawn in the final round:

Up a piece and with a powerful d-pawn, white can win slowly in a variety of ways. However, Sam found the attractive idea 39 Bxh6!, which forced resignation on the spot. If black takes the bishop, 39 … gxh6, then 40 d7 Ke7 41 g7 splits the attention of the black king.

These games were a good reminder to me of the varied ways in which passed pawns can constitute a serious advantage in the endgame. In the first two games, the passed pawns were more a long term, strategic advantage whereas the later two exemplified the ways in which passed pawns can fuel successful tactics.

With the caveat that 55 … d2 56 e7 d1=Q 57 e8=Q is still really difficult.

Among others. 39 … Kg8 is also strong and perhaps a more likely choice for the average human being.

Interesting!