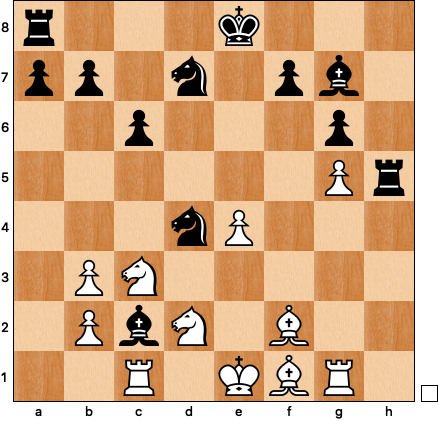

In his excellent book, Chess for Zebras, Jonathan Rowson writes about trying to solve a series of difficult problems during a training session with Artur Yusupov. Soon after beefing up his calculation skills, Rowson reached the following promising position against Alex Yermolinsky1:

Let’s turn it over to Rowson for a moment:

Here I had to decide whether it was safe to capture the pawn on a7. The experience of dissatisfaction I felt while working with Yusupov, especially in situations where I stopped my calculations one move prematurely, was fresh in my mind. So here I started looking move to move until I saw an exquisite detail at the end of the main line.

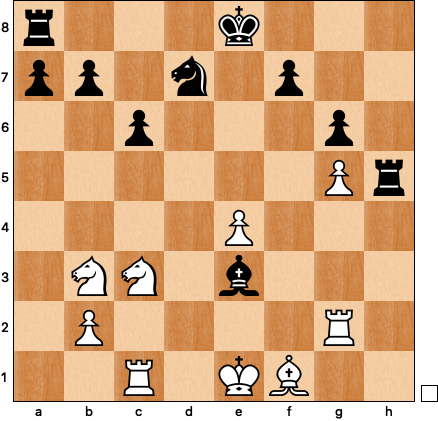

The game continued 19 Qxa7 Qc2 20 Rd2 Qc1+ 21 Kh2 Bg5 22 Re2 Bf4+ 23 g3 Qd1:

Rowson writes that he got to this position in his analysis and originally assessed it as “highly troublesome.” From the vantage point of five moves previous, it seems like black has found sufficient counterplay, but he had missed the backwards move 24 Ng1, which saves both loose pieces — in fact, Yermo resigned on the spot. Rowson states that

I believe I won, not because I was a stronger player, but because I was better concentrated than my opponent that day. And I was concentrated because of my recent training. Yermolinsky stopped his analysis in a position that looks highly promising for Black, but I gave my full effort to see one move deeper, and that made all the difference.

This concept of “one move more” has stayed with me ever since. It’s applicable to players of every ability level: those who can calculate only one ply would be better off calculating two, so on and so forth. It’s also a good sign of form, as I know that I’m going to have a decent tournament when I can push myself past superficial assessments by going just a little deeper.

The games of great players tend to feature interesting tactics and outstanding calculation, the kind of play that exemplifies the “one move more” principle. I was struck by the round one battle at Superbet between Gukesh and Praggnanandhaa, and not just because we could someday see them in an all-India world championship match. Here’s the position after Gukesh played 16 Nd2:

It doesn’t take a master to tell you that white is planning Ne4 to break the blockade on d6; the question is how strong this will be. After the game Gukesh recommended 16 … Bb7, finishing development and add pressure on d5 in anticipation of 17 Nde4. Now 17 … Qb6 should be OK, but 17 … Nxe4 18 Nxe4 Qxd5? 19 Bc2! is not, since 19 … Qc6 20 Rxd7! Qxd7 21 Nf6+! is a killer:

Pragg ended up playing 16 … Nxd5, clarifying the position on his own terms. This is an exceptionally risky choice, the kind of move I would reject for superficial reasons almost every time. Just look at the position after 17 Nxd5 Qxd5:

Once glance at 18 Be4 would have led me to toss the whole thing, but Praggnanandhaa had looked a bit further to see that 18 … Qd4 pins the bishop to the white queen. Now her majesty is exposed along the d-file, but Pragg had a counter planned here as well: 19 Nf3 (conveniently also protecting the Qh4) 19… Qc4+ 20 Kb1 Rb8:

I think it’s reasonable to expect most experienced players to calculate to this point, but now we’ve reached an example of Rowson’s “one more move” concept. I don’t know how far ahead either of the players saw when this sequence began on move 16, but I could imagine myself stopping here with the mistaken conclusion that black is relatively safe.

This is not the time to end one’s calculations! White has two interesting ideas, one that cashes out by winning the queen and one that increases the pressure against the black king. That Gukesh chose the wrong one is a testament to how difficult these positions can be.

The right choice was 21 Qe7! when black can hardly move. The Nd7 can’t move because of the threat of Rd8, but 21 … g6 (gaining luft on the back rank) 22 Rd6! is also a major problem.

Gukesh either missed or misevaluated something here, because 21 Bh7+ Kxh7 22 Re4 didn’t quite get the job done:

The black queen is trapped, but after 22 … Nb6 23 Rxc4 bxc4 black’s counterplay on the queenside allowed him to survive.

To review: black took what seemed to be a poison pawn, allowing a terrible skewer after Be4. By looking a bit further, he knew he had a counter: a lateral pin and a check gave him enough time to save his rook. But white had a counter to his counter, although not the right one, a bishop sacrifice to trap the queen. Any of these tactics is reasonably simple to spot in the moment, but to see the entire sequence from the start requires an impressive display of both concentration and imagination.

Gukesh seems at his best in deep tactical positions like this one, and his game against Pragg brought to mind his first win in last year's world championship match against Ding Liren:

Just as Pragg tempted fate by capturing on d5, Ding took a big risk leaving his bishop all alone on c2. Gukesh didn’t have to be asked twice, and played 19 e4 to cut off its f5 retreat. Ding’s idea became clear only after 19 … dxe4 20 fxe4 Ne6 21 Rc1 Nxd4 22 Bf2 Bg7:

He’s losing the piece, no doubt about it, but after the expected 23 Bxd4 Bxd4 white has to waste a move on 24 Rg2, with the hidden point that 24 … Bxb3 25 Nxb3 Be3 wins the g5-pawn:

Again, this is hard to spot from a distance, particularly since the Nd2 only moves at the last minute, which opens the diagonal for the bishop’s attack on the Rc1. But Gukesh played the clever 24 Ne2 instead:

All of a sudden it’s clear that black is busted. The Nd4 is hanging but if it moves the Bc2 remains trapped. The best Ding could manage was 24 … Nxb3 25 Rxc2 with two pawns for the piece, but he was unable to put up much resistance. It’s a very similar pattern to the previous game: black put his bishop on an active but dangerous square, allowing it to be trapped. Black had looked a bit further and had an interesting counter, aiming to win three pawns for the piece. But Gukesh once again had a counter to black’s counter, and in this case the extra material was enough to secure the win.

Tactics aren’t all there is to chess — without some kind of positional understanding the pieces won’t be on the right squares for the tactics to work in the first place — but even at the highest levels the ability to out-calculate one’s opponent is incredibly important. It’s hard to fight the urge to stop calculating by coming to a premature assessment, but it’s a really important skill that can just about always be improved.

Coincidentally, both Rowson and Yermolinsky showed up in my newsfeed this week: Rowson because he’s writing about chess again, here on Substack, and Yermo, sadly, because he just underwent emergency quadruple bypass surgery in Turkey — here’s the link to the GoFundMe to help with his medical bills.