I’ve been meaning to write about the idea of negative and positive trends for a while, and what luck—I got squashed in the last round of the Tuesday Night Marathon—and now have an excellent instructive example to write about.

I became aware of this idea from Alex Yermolinsky’s book The Road to Chess Improvement. The basic idea is that almost all positions are trending in one direction or the other. Good positions will sometimes get slowly better without a whole lot of decisive action; bad positions with sometimes deteriorate seemingly on their own. Yermolinsky devotes some time to talking about the difficulty of breaking negative trends. The challenge is that we often have to change out mind about the position by acknowledging that it’s bad and getting worse and then we have to figure out how to shake things up so that our opponent can no longer coast to victory.

Put another way, getting caught in a negative trend usually includes the following elements:

Some big misconception about the objective evaluation of the position, often about the relative value of the plans or dynamic potential available to each player.

An unwillingness to dramatically change the position, either because of the initial misevaluation or because it feels like any big shift will make matters worse.

Which leads to missing the real critical moments of the game and blaming the eventual defeat on subsequent tactical nuances rather than the real culprit: not sensing the negative trend until it’s too late.

Enough theory, here’s what it looks like in action:

Andy Lee (2328) - Daniel Cremisi (2401), Tuesday Night Marathon (5), 8/6/24

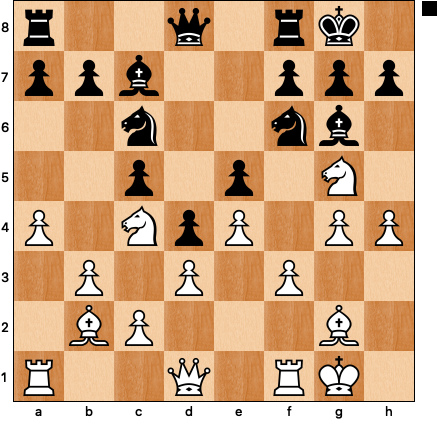

1 b3 Nf6 2 Bb2 e6 3 g3. I’m going to avoid in-depth analysis of the opening, but this is an important moment: usually white plays 3 e3, which is what I had planned in similar positions, but at the last minute I switched gears and played a line that I was less confident in overall, not really a good sign. 3 … d5 4 Bg2 c5 5 Nf3 Nc6 6 00 Bd6:

White has gone full hypermodern; this is the moment to decide how much center black gets to control. 7 c4 strikes me as an irresponsible entombing of the Bb2 after black plays 7 … d4, but the problem is that my actual choice, 7 d3, leads to the same kind of structure. The most common line is 7 d4 cxd4 8 Nxd4 00 9 Nxc6 bxc6 10 c4, with an equal position.

My opponent was quick to seize the extra space: 7 … e5 8 Nbd2 00 9 e4 d4 10 Nc4 Bc7 11 a4 Be6 and now it was time to think:

This position reveals one of the problems with the Nimzo-Larsen Attack: it’s possible to transpose into all sorts of other setups, but like it or not, you’re always going to have the bishop on b2. In this King’s Indian type position it’s terribly placed and is going to have to move again to find any kind of activity.

Misplaced pieces are an early warning sign that we might be experiencing a negative trend. If we try to keep playing the position “normally” our pieces will continue to lack scope and when something happens we will be ill-prepared to fight back. That’s why the one variation the computer suggests is 12 c3!? a6 13 cxd4 exd4 14 Ba3 Re8 15 Rc1:

The point isn’t that we’ve solved all of white’s problems but that we’re now in a better position to try to solve them later on: by transforming the pawn structure a bit the Ba3 and Rc1 are playing a greater role in the game than they were before. I was vaguely aware of this idea during the game, but decided to play “normally” by expanding on the kingside: 12 Ng5 Bg4 13 f3 Bh5 14 g4 Bg6 15 h4:

The computer isn’t a big fan of this g4-h4 idea, suggesting that 15 … Nd7! causes white problems: 16 Qe1 (16 Bc1 h6 17 h5 hxg5 18 hxg6 f6! is a disaster) 16 … Nb4 17 Qf2 Qe7 followed by f6 extricates the Bg6 and leaves black with a healthy edge. Instead black’s plan of 15 … h5 16 Nh3 a6 allowed white back in the game. The key position appears after 17 g5 Nd7:

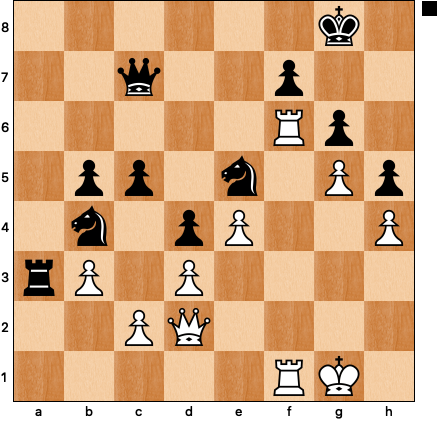

I felt optimistic here, a feeling reinforced by what felt like progress on “my side of the board” compared with black’s apparent lack of progress on the queenside. At the board, white’s f3-f4 idea felt far more important than black’s b7-b5. I did pause for a while here to consider 18 a5, stopping black’s play before embarking on my own. This would have been the right choice as after 18 … Nxa5 (18 … f5 is a good alternative) 19 Nxa5 Bxa5 20 f4 exf4 21 Nxf4 black can no longer capture the Nf4. Instead I chose the immediate pawn break: 18 f4?! exf4 19 Nxf4?! (19 Bc1 would have been a better choice, although black is still a little better after 19 … Ndxe4) 19 … Bxf4 20 Rxf4 Qc7 (black is less impetuous than white and solidifies the position before playing b7-b5) 21 Qd2?! (a strange refusal to improve the bishop via 21 Bc1) 21 … b5:

It’s time to take stock of the position. White’s knight is being driven to the side of the board. White’s bishops are fianchettoed and useless, the Bb2 still hemmed in by the black pawns and the Bg2 stuck behind the soon to be blockaded e4 pawn. With the exchange of the Nf4, white’s attacking chances on the kingside have stalled. On the other hand, black’s knights have e5 locked down with g4 and b4 as potential future destinations. The Bg6 has little scope but defends black’s king, which now looks more safe than white’s.

I wasn’t yet aware that my position was so much worse than black’s, that I was caught in a negative trend of about a pawn and a half of position lost over the previous four moves. I misevaluated two big positional features: I didn’t recognize the strength of black’s Ne5 blockade, which cannot be contested by my minor places, and I didn’t understand that black’s control of a-file will be more useful than my control of the f-file. This explains my next mistake: 22 axb5? (22 Na3, keeping the queenside as closed as long as possible was much better) 22 … axb5 23 Na3 Ra5 24 Raf1 Rfa8:

A few moves back I assumed that I would play 25 Qf2 in this position in order to meet 25 … Rxa3 26 Bxa3 Rxa3 with 27 Rxf7, although even here black is winning after 27 … Nce5. The problem is that black has no need to rush anything: he just plays 25 … Nde5 to shore up f7 and white is helpless against the threats of Rxa3, Ng4, etc.

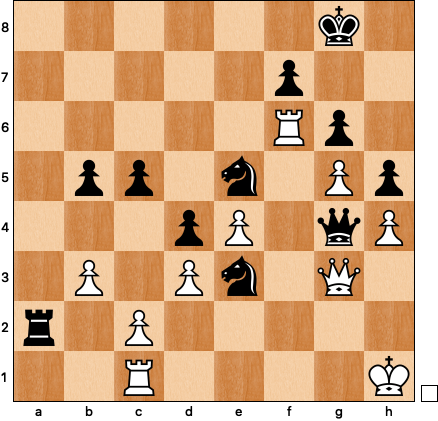

The position is already objectively lost, which suggests that there’s nothing to be lost by playing 25 e5, getting the bishop some scope and trying to mix things up, but instead I once again thought I could play normal looking moves to defend the jumbled pieces on the queenside: 25 Qc1 Nde5 26 Bh3 Nb4!:

After the game I blamed the fact that I missed Nb4 for my defeat, when nothing could be further from the truth. There are winning tactical ideas for black because his positional is strategically winning; I didn’t get unlucky1.

The point is that a knight sacrifice on d3 is going to win in two different ways: after the queen moves black can pick up the exchange and roll in the center, or he can play Nxb2 and Rxa3 to regain the piece. I conceded that I was losing material one way or another: 27 Qd2 Rxa3 28 Bxa3 Rxa3. It would be nice to think that by getting a rook in return for those two sad minor pieces white gets a little play, but the black knights rule the roost, and all there was left to play for were tricks: 29 Bf5 Bxf5 30 Rxf5 g6 31 Rf6:

Here I hallucinated some tactics: 31 … Ra2 32 Qf4 Rxc2 33 Rxg6+! (the only swindling idea that I could find the entire rest of the game) 33 … Kf8 and now I saw 34 Rh6 Nf3+ 35 Qxf3 Qh2#, not noticing 35 Rxf3 and there’s no mate.

My opponent finished off the game in excellent style, as there’s no need to give white anything to hope for: 31 … Qd7 32 Qh2 Nbc6 33 R6f4 Ra2 34 Kh1 Ng4 35 Qg3 (35 Qe2 Ne3 36 Rxf7 Qh3+ 37 Kg1 Nxf1 and wins) 35 … Nce5 36 Rc1 Qa7 37 Rff1 Qb7 38 Qf4 Qe7 39 Qg3 Qe6 40 Rf4 Ne3 41 Rf6 Qg4:

Sadly 42 Qxe5 is met by 42 … Qg2#, and 42 Qf2 Nxd3 is curtains, so 42 Qxg4 hxg4 43 Rb6 g3 and I finally threw in the towel; there’s no stopping the g-pawn.

The irony is that black played the kind of chess that I’d been hoping to work on in this tournament: simple positional play that takes advantage of positive trends in the position to slowly push the opponent off the board. I guess if I’m going to lose, losing while getting a positional chess masterclass isn’t the worse thing in the world, but it’s always a shame to feel like you haven’t pushed your opponent very hard. I’ll be looking to bounce back next week as there are only two rounds to go.

Pop culture analogy: the designers of Jurassic Park didn’t get “unlucky” that they had a crooked scientist on staff who tried to steal some embryos and let all the dinosaurs out. They were operating from a bad strategic position in the first of having messed around with Mother Nature by de-extincting a bunch of carnivorous death machines.