I played in the U.S. Amateur Team West over President’s Day weekend, my 22nd USAT tournament since first playing in the Midwest1 edition back in 2000. The team format tends to bring out my best, and I can claim one USAT victory and top board prize (5-0 at the USAT Midwest, 2003), and one best game prize (versus Robby Adamson, USAT West, 2006), as well as the strongest player I’ve held to a draw (Alexander Onischuk, USAT East, 2014).

Despite that bit of history2, I didn’t have high expectations going into this year’s event. It had been five years since I’d played a three day tournament in person — that was the USAT East in 2020, just weeks before the COVID pandemic — and I didn’t have a lot of faith in my stamina past day one. I also didn’t do much in advance other than a hundred or so easy tactical puzzles and prepping a very dodgy line of the Sicilian. I was looking forward to seeing my high school and college friends that make up the team I’ve played with for most of those 22 USAT tournaments as much as the chess3.

I came home feeling completely exhausted, a little disappointed with my final result of 4-2, but relatively happy with my decision making — that is, until I ran the games through the computer. I’m going to use this space to think through my play in all three stages, starting with the middlegame in the this post and the next, and then moving on to the endgame and opening stages.

Some Methodology

The best way to evaluate one’s middlegame play is to consider the critical moments. That is to say, as the position was about to undergo some kind of transformative change4, how well did my decision making process work? This is a messy process, as decisions in chess are based two forms of information: specific calculations from the position on the board, and general chess knowledge, both the stuff we’re conscious of and our more hidden, intuitive feelings.

There are five general ways that this process can go wrong, which makes it all the more amazing that anyone can play chess well at all:

Missing the critical moment entirely. Jonathan Rowson calls this a lack of sensitivity in his books, a nice description of the all too common error of realizing that it’s too late to solve the problems of the position, that ship has sailed.

Awareness that it’s a critical moment, but failing to see all the options. This is an incredibly frustrating feeling that is typically solved through increased exposure to tactical patterns and opening tabiyas.

Making the wrong choice because of miscalculation or insufficient calculation.

Making the wrong choice because of a misapplied or misunderstood piece of general knowledge.

Making the wrong choice because of a miscalibration between calculation and knowledge/intuition, overemphasizing one over the other or failing to find convergence between the two.

I’ll be referring back to these five areas periodically, now let’s get to the chess!

Round One: Andy Lee - Zelin Feng

It’s a Northern California tournament, so of course I’m playing a kid in the first round5. My attempt to play the English without preparation hasn’t gone great, as I have to choose between giving up my b2-pawn for no compensation or losing the bishop pair:

I’m the sort of person who is often tempted to give up material to justify future attacking play, so I spend a bit of time on 13 Bg5 Bxb2 14 Rc2 Bg7 15 h3 before deciding that there white’s compensation was hazy at best and that discretion is better part of valor. After 13 Bd4 Nxd4 14 Nxd4, black faced a critical moment of his own:

He has to decide whether or not to play concretely (going after the b-pawn) or abstractly (biding his time with the bishop pair). It’s essentially a battle between the calculation muscle and the intuitive instinct, and as is typical in kids, the concrete solution won out. I would have preferred 14 ... Bd7 to continue the game as it is, trusting in the B’s, but my opponent played 14 … Bxd5 15 Bxd5 Qb6 16 e3 Nf6 17 Bg2 Qxb2, only to sink into thought after 18 Qa4:

This is a typical calculation mistake that Kevin Lincoln covered nicely on his Substack: it’s really important to continue the variation beyond the initial win of material. You could even say that this is where the variation really begins. In any case, the problems confronting black are evident: his queen is very poorly placed and he’s in danger of losing everything on the second rank after Rb1xb7.

I’d seen that this variation was good for white and probably tempting for my opponent back on move 13, and I had no trouble converting my advantage. This was a good start to the tournament, but also my easiest game by far.

Round 2: David Zhou - Andy Lee

We were playing the Stanford team, and as a kid from Berkeley, there’s nothing I like better than beating Stanford. I got a surprising good position from the dodgy Sicilian I had prepared, and I could tell my opponent was struggling: his last two moves were Ra1-c1 followed by a2-a3.

This is another concrete versus abstract critical moment. If white had played Qe2 instead of a3, I was planning Qg6 and f5. But now it’s possible to switch directions and play 16 … Bxa3, which sharpens things considerably. 17 Na4 is forced, hoping to embarrass the bishop, and here I’d initially planned on 17 … b5 18 Nb6 Bxb2 19 Nxc8 Rxc8 20 Rb1 Rxc2, with three pawns for the exchange. The problem is that 17 … b5 18 bxa3! bxa4 19 c4 isn’t bad for white at all, so I spent some time recalibrating, rejecting 17 … Bb4 because of 18 Bb6, when it feels like the bishop is getting trapped (or forced back to c5).

The word “feels” is a big clue to how I’m processing the position: it clearly calls for some intensive calculation, but once I saw 18 Bb6, I abandoned 17 … Bb4 for another variation. The computer says that there’s no need wallow in negativity, giving some ideas that I didn’t come close to considering: 18 … Ng6 19 c3 Nf4:

No need to take care of the bishop when 20 cxb4? Rxc1 21 Qxc1 Ne2+ picks up the white queen. The tactical soundness of the black position is reinforced by the idea of Qd7 in some positions (so that after cxb4 and the exchange on c1, black can simply play Qxa4) and the potential mate threats generated by queen and knight.

Back to the game:

I played 17 … Qe4, which I thought at the time was an improvement on both 17 … b5 and 17 … Bb4. The problem is that now white can take the exchange, thanks to a neat trick: 18 Nb6 Bxb2 19 Nxc8 Rxc8 20 Rb1 Rxc2 21 Bc1!

I’m pleased to say that I foresaw this move, somewhat less pleased to report that I filed it away in the “I’ll deal with it when we get to it” part of my brain, hoping that it’s not a serious problem. But it is: after 21 … Rxc1 22 Rxc1 Bxc1 23 Qxc1 there’s no time for 23 … Qxd5 24 Qc7 Qe6 25 Qd8#. Black has to make luft and white has time to play Qc7xb7 with enough counterplay to survive.

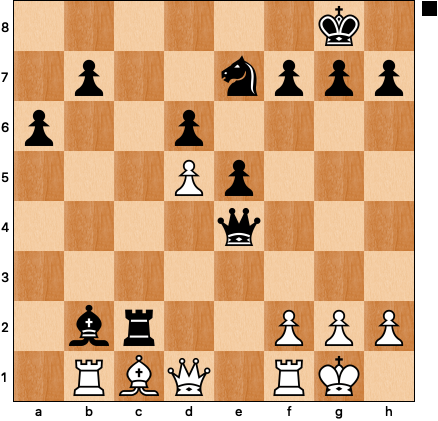

Fortunately, my opponent erred with 18 c3 b5 19 Ra1 (19 Nb6 is once again the bad-for-white version of taking the exchange for three pawns) 19 … bxa4 20 Rxa3 Rc4:

The d-pawn is falling, and black is pretty clearly on the verge of winning. I didn’t convert very smoothly, but we’ll save that for the endgame recap. My calculation also wasn’t perfect, but the choice to complicate was the right one, and I saw two of the three variations accurately to the end. As a result, I was feeling pretty good about myself going into the second day of the tournament.

Round 3: Andy Lee - Andrew Zou

Due to some extreme rustiness on the part of my beloved teammates, our team score was 0.5/2, so we were paired down against another team of kids. My opponent tried his best to play the center game with black against the English, neglecting development to install his queen on e6:

I was sensitive to the idea that I had a fleeting opportunity to open the game with 8 d4, but I wasn’t sure how strong it was. There was the question of how big white’s advantage is after 8 … cxd4 9 Nxd4 Bxd4 10 Qxd4 00 (quite big, almost +2 according to the computer), as well as the following variations to calculate:

First, 9 … Qe7 is met by 10 Nf5! (a move that was not on my radar at all) 10 … Bxf5 11 Bxb7 Bh3 12 Bxa8 Bxf1 13 Qxf1, and white is close to winning, although there are still some technical details to sort out.

Second, 9 … Qd6 10 Ndb5 Qxd1 11 Rxd1 is good for white, but there is also the bone-crunching 11 Nxc7+! Kd8 12 Rxd1+ Kxc7 13 Bf4+ Kb6 14 Na4+ Kb5 15 Nxc5 Kxc5 16 Rac1+ and white is completely winning:

This is the sort of stuff I tend to find when I have both sufficient energy and good form. I’m certainly disappointed that I made the choice on who my opponent was rather than calculation, deciding that against a kid I should go for a slow maneuvering game. After 8 d3 00 9 a3 a5 10 Bd2 Nc6 11 Rc1 Rd8 12 Na4 Be7 13 Nc5 Bxc5 14 Rxc5 black is the one doing well:

He’s played actively so far and should keep it up with 14 … e4! 15 Ne1 b6! (a move I missed) 16 Rc1 Bb7 with an excellent position. Instead after 14 … Nd7 I got exactly the kind of position I wanted, which involved winning a very tedious endgame.

If there’s a pattern so far, it’s that I was less willing to calculate variations each successive round, substituting a superficial intuitive approach as fatigue set in6. This is a combination of mistakes 3 and 5 — I didn’t see all the variations in round three because I didn’t really try, clearly a case of insufficient calculation in a position that demanded it. We’ll see if this pattern continued when working through rounds 4-6 in the next post.

Now rebranded as the USAT North, as if the cardinal points were more important than the name of actual regions of the United States.

Which I’m sure I’ll find an excuse to write/brag about here at some point or another.

It turned out that they were more rusty than I was, if such as thing is possible — clearly they should spend more time blogging about chess.

Transformative change including (but not limited to) important exchanges of material, changes to the pawn structure, decisions about whether to play aggressively or conservatively. It’s the stuff you can’t undo or have only a fleeting chance to put into action.

Given that everyone on my team is in their 40s now, we (mostly me) were cranky about the conduct of the kids in the tournament. The problem seems to be that there are so many kids in the tournaments they play they haven’t yet been acculturated to the unwritten rules of adult tournament chess: no offering draws in terrible positions, no playing on down a queen forever, no telling your opponent that you’re leaving the board to go to the bathroom, no standing up and dancing in the vicinity of the game, etc.

It doesn’t take long these days!