At the risk of sounding old and grumpy, I am generally not a fan of the modern trend towards the elimination tournament, the rounding up of eight or sixteen talented players to face off in a series of mini-matches that begin in classical and often end in some kind of blitz or armageddon. I much prefer knowing that all the players who played in the first round will be there in the final round1, with the potential for high drama as in last year’s candidates event.

For the elimination tournament to shine, one of two things need to happen: that there are many, many players involved, as in the FIDE World Cup, or that there is a compelling final match. In the case of the recently completed American Cup, we got a very interesting final match followed by a rematch, as Tatev Abrahamyan got a second shot at Alice Lee after a rapid takedown of Irina Krush in the loser’s bracket.

I was initially drawn to the match thanks to Lee’s creative play in the first game. She knocked Abrahamyan off balance with an unusual implementation of a common plan against the King’s Indian:

The normal way to play these kinds of positions is Rab1 followed by b2-b4 to slowly turn the screws on the queenside. Despite white’s space advantage it can be difficult to make headway, and black will eventually organize counterplay on the opposing wing. I was very impressed by what Lee chose instead: 15 Ng5! Qe8 (15 … fxg5? 16 Bxg5 followed by Bxh6 wins a pawn) 16 Ne6! Bxe6 17 dxe6, removing what is often black’s best minor piece and creating a wonderful outpost on d5:

At first glance the position feels very uncomfortable for black. It’s unlikely that Abrahamyan expected Ng5-e6, and she couldn’t have been happy with her poorly placed minor pieces as the position begins to open up. Her choice, 17 … Qxe6, looks sensible, following the old adage “If I’m going to suffer, I might as well have a pawn for it,” but perhaps it wasn’t necessary to suffer at all. With 17 … Nc7! 18 Qxd6 Ne6 black should equalize, as the rapid transfer of the knight from a6 to d4 covers many of the holes in the black position.

As it was, white’s initiative threatened to reach massive proportions. The game continued 18 Rfd1 Nf7 19 Nd5 Nd8 20 b4 Qf7 21 b5:

This is the kind of position Lee was dreaming about when she chose the plan with Ng5. It’s generally hard to avoid forming narratives during the course of the game, and had I been in Abrahamyan’s shoes I would have had a hard time shaking the feeling that something has gone terribly wrong and that I’m about to get run over. The move she chose, 21 … Nb8?, is so passive that it seems to confirm she had little hope for her position.

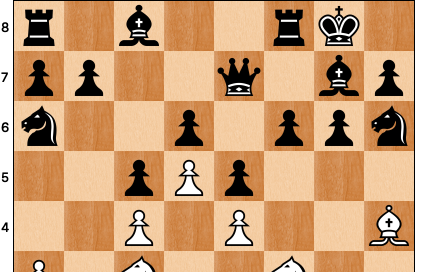

However, this is exactly when black could have put up greater resistance had she played 21 … Nc7! 22 Nxc7 Qxc7 23 Qxd6 Qc8! Black is momentarily passive, but her pieces cover the key squares, and Ne6-d4 is once again going to solve a lot of problems. After both players erred on the next move, Lee resumed her slow pressure campaign, eventually reaching this position:

Black’s last move, Rd8-c8, allowed a pretty finishing sequence: 35 Rd6! Qf7 (if 35 … Bxd6 36 Bxf6+ Kf7 37 Nh6#) 36 Rxf6! Qxc4 (once again 36 … Bxf6 37 Bxf6+ Kg8 38 Nh6#) 37 Nxe5 and black resigned.

To play through this game quickly gives the impression that white was in control the whole time, a narrative simplification that was often applied to games annotated before the computer era, when the result of the game was often used to assess the quality of each player’s decisions. A slower examination with the computer reveals that black repeatedly missed multiple opportunities to put up significant resistance, in each case via the same mechanism, planting one of her knights on d4. Lee played well, but she didn’t play perfectly, and the difference in match play is often which player is able to put up greater resistance when they find themselves in such difficulties.

The second game of the first match featured far more resistance from both players, and therefore turned out to be far more interesting to annotate. Lee needed only a draw to secure a spot in the second finals, and she appeared in good shape to do so:

Black’s play in the opening has been a success. Her unopposed bishop is blockading white’s entire kingside, her central structure restricts white’s remaining bishop, and she is in control of the next important pawn break — 13 … f5! — a sure sign that the she has the initiative. The next few moves were natural. After the trade on f5 Lee returned her bishop to blockade duty on h3, then pushed d6-d5 to restrict white’s knights and doubled on the f-file. Abrahamyan reorganized along the first three ranks, limited by the lack of good squares for her pieces and her weak f-pawn:

This is a very interesting position, not just for what is specifically happening on the board but for the general type of problem that it represents. Imagine that you’re playing the black pieces. There’s no question that you are better — a comparison of piece activity, central control, and targets to attack confirms this — but it’s not all that clear what to do next. The computer puts black at about +1, which tells me that white’s position is unpleasant but also that there’s no immediate way for black to take advantage.

This is an unpleasant feeling. Black has made the most of her positional plusses, taking over the initiative while reducing her opponent to passivity. And yet the initiative has run its course, further forcing moves are unlikely to pay great dividends. A similar problem shook Gukesh in the first game of his match against Ding last winter: he was playing aggressive, confident moves and then almost out of nowhere lost control of the position.

Lee took the most direct route, playing 19 … Bd8 with the intention of Bd8-a5xd2 followed by Rxf3. Given the match situation, I would have recommended (but perhaps have also lacked the patience) to slowly improve black’s pieces — after all, Lee only needed a draw, and it’s hard to see how white is going to make a threat, let alone win the game.

Abrahamyan, to her credit, immediately found ways to remind her opponent that both players can make threats, going after the c5-pawn straightaway: 20 Ba3 Qd6 21 Nd1 Ba5 22 Qe3:

Already it feels like black has lost a little control, that she would like to go back to move 19 and play something simple like Bd6. True, she can win a pawn with 22 … Bxd2 23 Qxd2 Rxf3, but 24 Qa5 wins it back with a much improved white position: no more weakness on the f-file and potential control of the dark squares. The alternatives are all admissions that the plan hasn’t worked out, both 22 … Bb4 or 22 … Qe7 show that white has managed to upset black’s plans.

Lee reacted very poorly, with a move that I would not expect her to play more than one time out of a hundred or even a thousand. She chose the anti-positional 22 … d4?, an invitation to the white knights to assume healthy outposts in the center, the kind of tradeoff that Abrahamyan would have been happy to sacrifice a pawn to achieve. Jumping ahead about a dozen moves brings us to a whole new state of affairs:

Now it’s black’s position that looks disorganized. What exactly is the rook doing on e3? Abrahamyan played 36 h6 Qd8 37 Rdf2 Qxh4 38 gxh4 Nxh6 39 Bxe3, picking up the exchange, but the computer shows a path to victory in the middlegame: 36 Rdf2! Re1 37 Rxf7! Bxf7 38 Rxe1 Qxe1 39 h6!

This is a very nice positional solution; black is helpless on the dark squares, and the threats of either Qg5 or Qe7 are deadly. Nevertheless, Abrahamyan’s solution was a practical one, since there is much less risk involved in being up the exchange in the endgame than down the exchange and attacking in the middlegame. She might have expected the game to end quickly, but Lee continued to find ways to set small problems. Here’s one example:

Normally you’d expect black to play something like 48 … Rxe4 49 c5 Kf6 50 c6 Nd6 51 Rd8 Nb5 52 a4 Nc7 53 Rd7 Ne6 54 c7 and resigns, as the c-pawn is just far too strong. Instead Lee played 48 … Nd6! and after 49 Rxg5+ Kf6 50 Rcg8 Nxe4 51 Rg2 h5 white is still winning, of course, but she’s no closer to the finish line than before, as the c-pawn can’t advance and black’s pieces are all active:

The evaluation of the position is still about +5 for white, but black’s pieces, including her king, are working together to create the impression of counterplay, counterplay that is more threatening in the imagination than in reality. After 52 Rf8+ Ke7 53 Ra8 Rg4 54 Rxa7+ Kf6 Abrahamyan had to decide whether or not to trade rooks:

It turns out that there’s nothing wrong with 55 Rxg4 hxg4 56 Rd7, but I admit that this would not be my first choice with little time left on the clock to double-check my calculations. After avoiding another winning rook trade a few moves later, Abrahamyan sacrificed the exchange to reach what must have felt like a completely winning rook and pawn ending:

I like to think of mistakes in the endgame as equivalent to walking closer to the edge of a cliff. Often a position is still technically winning after a number of a suboptimal choices but eventually we will reach a position in which one further mistake will send us over the edge. That has come to pass, and while 63 a6! Kb6 64 Rxh4 still wins, it is the only winning line. Tragically, Abrahamyan chose 63 Rxh4? only to find that after 63 … Kb4! black had finally secured the long sought after draw.

This game ended the first match in Lee’s favor, and although the players traded wins in the classical portion of the rematch, Lee prevailed in tiebreaks. I’m sure that Abrahamyan, who played a really impressive tournament overall, was unhappy about her missed chances in this game and in the finals more generally. I can sympathize2, having felt the agony of missed wins at the end of more than one long struggle. It’s a good reminder that resistance is almost always possible, and that sustained resistance can make winning a won game difficult for even very experienced and strong opponents.

Barring a Carlsen-Niemann fiasco, I suppose.

As can most chessplayers, I’m sure.

She didn't win, but Tatev's play was the highlight of the tournament for me. Women's sections of these recent St Louis tournaments have been routinely more compelling.