Never Trust Your Opponent

They're probably just as confused as you are, and they're definitely trying to trick you.

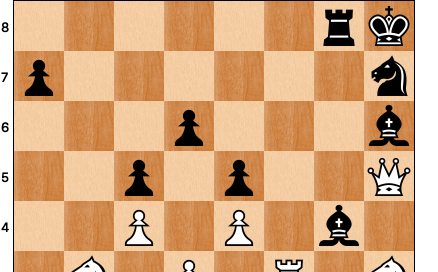

A little over a week ago Magnus Carlsen and Hikaru Nakamura met up in the finals1 of yet another rapid elimination match — they’ve played so many of these matches by now that I’m beginning to think of them as the Kasparov and Karpov of the new generation of faster time controls. The final position of the last game has been widely circulated on various chess websites, but if you haven’t seen it, here it is:

Carlsen, up a point in the match and needing only a draw to advance, decided to end things in style by sacrificing an exchange to reach this very promising looking position. The Qh5 is attacked, the Rf3 is attacked, Rxg4 is met by Qxf3+, winning everything. Nakamura resigned but soon discovered that he’d missed Rfg3!, pinning the Bg4 to mate on g8 and turning the tables on his Norwegian rival.

What happened here? Rfg3 isn’t a hard move to spot for someone of Nakamura’s caliber; heck, it’s not particularly difficult for someone like me. However, moves that can be simple to find in isolation can be quite challenging within the specific context of the game, particularly when one’s opponent is strong and their moves and plans begin to dominate one’s own narrative of how things are going. Sometimes the brain skips over the “let’s calculate and assess the position rationally” step in favor of “I subconsciously believe that what my opponent is doing makes sense and I’m probably screwed.”

I have a long personal history with trusting my opponents more than they deserve, but before looking at some examples it’s important to remember that automatically refusing to trust your opponent’s ideas is just as problematic. Here’s a case from the distant past:

White saw that he had a tactical opportunity and played 13 Nxb5! I saw a hanging knight and barely had time to think “what a chump!” before snatching it off the board. Of course 13 … axb5 14 Bxb5 is game over. My coach was horrified that I wasn’t even looking one move ahead, a common problem in my 1200 days, which brings us to a common theme in these examples: clear-headed calculation is the remedy for both too much trust and not enough.

A year later my rating wasn’t much higher, but I was on the cusp of rapid improvement2. Playing in the middle school Nor-Cal Championships, I encountered my first 1700-rated opponent as well as my first Benko Gambit:

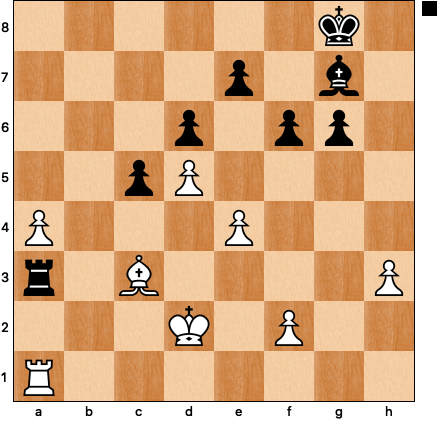

Black confidently bashed out 31 … Rxc3 and I now knew enough to stop and think when encountering a surprising move. I saw the discovery and the skewer, mentally congratulated my opponent on his good play, and decided to take a shot at running the a-pawn: 32 a5 Rb3 33 a6 Rb8 34 a7 Ra8. Stymied, I resigned a few moves later.

After the game Surlow’s first words were “You could have won!”3 before showing me 32 Kxc3! f5+ 33 Kc4! Bxa1 34 a5:

On the one hand, this was an idea that I had not encountered before; it wasn’t in my toolbox. On the other, it was the kind of creative solution that I was becoming more adept at finding over the board. Unfortunately, in this case I wasn't thinking about calculating my way to a creative solution but was instead feeling impressed by my opponent, his high rating, his eye for tactics.

As a side-effect of making master I became much harder to fool, but the situations in which which I blindly accept my opponent’s ideas tend fall into a common pattern:

I’m playing someone higher rated.

I’m not feeling very confident in my understanding of the position.

In the absence of good ideas of my own, I am impressed by the logic of my opponent’s play, seeing their plans as inevitable rather than part of an ongoing struggle.

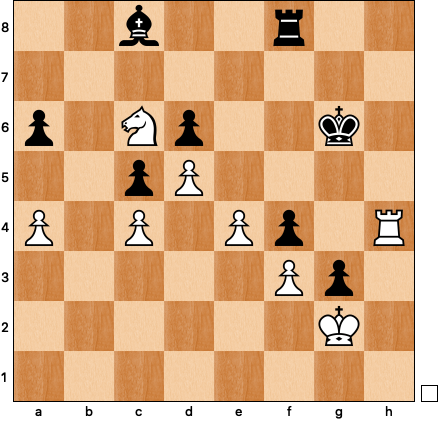

Here’s a good example from a tournament in which I was generally in good form, the 2005 HB Global tournament in Minneapolis4. I’d been suffering on the black side of a King’s Indian for quite some time, and my main strategic goal had been to imitate a turtle and hope that I could keep the white pieces out of my position:

This passive thinking did not serve me well when white played the unexpected 57 Rxf4. I was aware that 57 Ne7+ Kg5 tempos the rook and saves the f-pawn, but after 57 … Rxf4 58 Ne7+ it seemed like all my pawns were falling. All I could imagine was an unstoppable phalanx of white pawns coming down the board. I played 58 … Kf6? 59 Nxc8 Ke5 to save the d-pawn and stem the tide, and I eventually managed to hold a long and unpleasant king and pawn endgame. However, the game could have turned out very differently if I had remembered that I too could make threats: 58 … Kg5! 59 Nxc8 Rf8! 60 Nxd6 Kf4:

White has achieved part of his goal, three connected passers in the center, but the black pawn on g3 still lives and, more importantly, the rook is much stronger than the knight5. Black’s next moves will be Rh8, Rh2+, and Kxf3, which means that white’s creative sacrifice could have easily cost him the game.

It’s obviously important to think about what our opponent is trying to accomplish, but in doing so it’s possible to trick ourselves in the process by getting into a “they’re planning x if I do y, but they won’t expect this other move, z, that prevents their plan entirely.” Sometimes our opponent’s plans aren’t actually that good, and trying to avoid them entirely is another form of misplaced trust in the opponent:

I paused for a think in this position because I couldn’t for the life of me figure out what white was up to. Or rather, I knew exactly what he was planning, but it didn’t seem to work out. White has delayed Nf3 because he wants to play f4, Bf3, and Ne2-g3 to gang up on the weak h5-pawn. That’s all well and good if black shuffles the king between f8 and e8, but more concretely 15 … Nc6 16 f4 Nd4 17 Bf3 is much too slow.

It took me a moment to realize that white’s plan is to play 17 Rxd4!? cxd4 18 Nf3 instead:

For the exchange white is going to have a pawn and a nice outpost on d4 with possible future chances to round up h5. Black doesn’t have much going on, but an exchange is an exchange, and I would have been better off fighting directly against my opponent’s idea. Instead I left my knight on c6 and made an empty show of pushing pawns to a4 and b4 while he executed his secondary plan, f4, Bf3, and Ne2-g3xh5, and I never had much of a chance.

A few weeks ago I wrote about the “one more move principle” when calculating, and this kind of thinking solves the tactical trust problems of the first three examples: one more move and I’m not recapturing on b5 and hanging my queen, I’m finding Kc4 against Surlow, and I’m looking beyond white capturing on d6 in the game versus Ortiz. The final game, against Luke Harmon-Vellotti, is much more difficult, as it requires good judgment as much as good calculation: that’s the kind of thing that separates the masters from the class players and the grandmasters from the masters.

Winners bracket finals that is, not final finals.

By the end of the year I had broken 1800.

Not really what anyone enjoys to hear from their opponent after losing, but hey, we were in middle school.

I’ll be writing a more complete retrospective about this event sometime over the summer.

And the black king is much stronger than the white king.