This is the third in a series about the best and worst world championship matches of the 21st century. Here’s a link to the first article, which describes my methodology, and the second, which ranks the worst three matches, numbers 12 through 10.

#9: Vladimir Kramik-Peter Leko, 2004 (25 points)

Legitimacy (10th Place, 3 points)

The decision by Kasparov and Short to break from FIDE in 1993 led to a uncertain qualifying process in the early 2000s. The 2004 match took place in the context of the failed Prague agreement that was meant to reunify the chess world. Kramnik and Leko were initially intended to play a semifinal match, with the victor playing a final match against the winner of the Kasparov-Ponomariov.

The failure of this other semifinal match to materialize meant that Kramnik-Leko became, by default, a match for the championship itself. Leko’s road to the match was a bit strange: he came in second in group play in the Dortmund candidates tournament but emerged triumphant when he defeated Topalov in the knockout finals1. He acquitted himself well enough in the match, but the lack of Kasparov lowers the legitimacy score dramatically. It would have been fascinating to see what the thirteenth champion would have cooked up in a return match with Kramnik had he been given the chance.

Excitement (4th Place, 9 points)

While this match had its ups and downs (see the next section), it peaked at the right time, as Kramnik had to win on demand in the final game to keep his title2. The fact that he finally did so, after coming so close in games twelve and thirteen, elevates this match above many of its competitors.

Why doesn’t the excitement factor rank higher than fourth place? There’s some tough competition out there: a number of other matches have had similarly exciting finishes while maintaining a higher level of tension throughout the early stages. This match had some very exciting games in the first eleven rounds, but the excitement waned at times as Leko seemed to want nothing to do with the white pieces, content to draw out the match3.

Chess Content (6th Place, 7 points)

It was more difficult to rank Kramnik-Leko in this category than any other. On the one hand, perhaps no other match has produced so many dramatic and interesting games. However, no other match was so badly marred by grandmaster draws.

Let’s start with its strengths: game one, an impressive grind in which Kramnik, playing black, sacrificed his queen and went on to win. Leko returned the favor in game five, in an even more difficult ending:

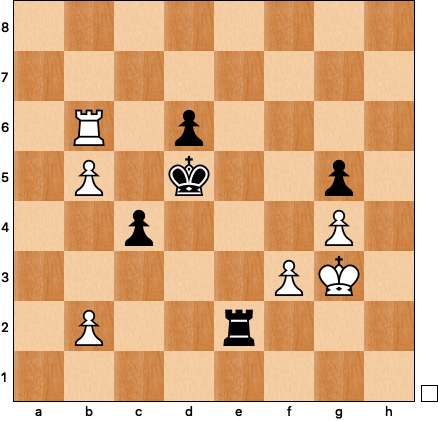

Black to move will play Bf6+ and the position is clearly drawn thanks to the defensive presence of the bishop on the long diagonal. This is only true thanks to white’s fractured pawns; if Leko had a better structure (say f4-g3-h4) he could still win by improving his position and breaking the fortress with a well timed g4 sacrifice. However, the bishop is not yet well placed, and Leko played 61 Rc7+, forcing the king to occupy the square intended for the bishop. After 61 … Kf6 62 Kd5 Kramnik erred: 62 … Bg3? 63 Rc6+ Kg7 64 Ke5. He could have instead rerouted the bishop with 62 … Be1! 63 Rc6+ Kg7 64 Ke5 Ba5, stopping Rc7+ and threatening Bc3+ if white’s rook leaves the c-file; as it was he went on to lose.

Leko took the lead with a victory in the eighth game (which we’ll return to in a moment), but after a series of draws a desperate Kramnik played the Benoni and was on the verge of tying the match with the black pieces:

Black is down a pawn for the moment, but it’s clear that he’s got all the winning chances: Rxb2 is coming and white will struggle to contain the c-pawn. Leko found an amazing defensive idea: 46 f4! Re3+ 47 Kf2 gxf4. It may look like white has lost a pawn for no reason, but the time gained (black still has not captured on b2) and the creation of the passed g-pawn was enough to hold a miraculous draw.

The final game of the match was no less impressive. Leko played passively and Kramnik, invoking the spirit of Capablanca, was able to invade with his king, knight, and rook, to win the game and keep his title.

If we were judging this match on endgame prowess in these decisive games alone, it would score quite high4. The problem is the number of games that didn’t make it to the endgame—or even to the middlegame—numbers 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, and 11. In the end, sixth place, in the middle of the pack, feels fair to me.

Legacy (7th Place, 6 points)

This match was notable for a number of reasons: it marked the first time in twenty years that Kasparov had not been part of the title match (and pushed him towards retirement the following year). The attempt to reunify the title would have to be postponed; FIDE crowned Rustam Kasimdzhanov after his victory in the 2004 knockout championship.

But most importantly, Kramnik taught us to never trust anyone, most of all our seconds5:

Kramnik, still in the preparation from his team, sacrificed his queen for a rook and the threat posed by his passed a-pawn. Leko convincingly refuted this idea over the board: 25 … Qd3! with the point being that 26 a7 Qe3+ 27 Kg2 Bxf3+ 28 Nxf3 Qe2+ 29 Kg1 Ng4! and black’s attack crashes through even though white queens with check.

At times I feel like I might have rated this match a little low. It was a great struggle—but only if we focus exclusively on the highlights.

#8: Vishy Anand-Magnus Carlsen, 2013 (26 points)

Legitimacy (3rd Place, 10 points)

This was the match the chess world had been waiting for since mid-2011, when Carlsen took over the number one spot on the rating list. His path through the candidates tournament was unsteady, as he needed some help from both Vasyl Ivanchuk (who beat Kramnik in the final round) and the tiebreaks after losing to Peter Svidler with the white pieces.

Nevertheless, Carlsen was the favorite against Anand, who had slipped to number eight in the world. Anand’s play the previous year against Gelfand had not been close to the quality of his games in 2008 or 2010, and his decline is a small ding to the legitimacy ranking. At the time of the match it was easy to imagine Carlsen as world champion; it would have felt a bit strange if Anand had managed to hold him off.

Excitement (11th Place, 2 points)

After a slow start, the excitement level increased dramatically in games four through six, the obvious peak of the match. However, the story that this peak told was not particularly exciting. Carlsen took a lead of two games, thanks to consecutive wins, and the way in which he won made it hard to imagine Anand mounting a comeback. Carlsen was clearly the better endgame player, and thanks to the Berlin he had no trouble avoiding the kinds of complex and tactical positions that had brought Anand success in his previous title matches.

After being ground down in the endgame in games five and six, Anand slammed on the brakes. Carlsen was happy to make draws, and it wasn’t until game nine that Anand again tried to win. After a blunder Carlsen was up three games and the match was essentially over. It was a one-sided affair: at no point was Carlsen in any serious danger of losing.

Chess Content (10th Place, 3 points)

Carlsen’s extraordinary endgame talent was on full display, as the best games of the match were decided after move 50. The endgames weren’t as compelling as those from the previous match in this series, Kramnik-Leko, but there were some notable moments.

The first came in game four:

Anand, trying to do the impossible crack the Berlin endgame, had just played Nc3-e2, to which Carlsen, quoting Fischer, replied 18 … Bxa2! The point is that 19 b3 c4 20 Ndc1 cxb3 21 cxb3 Bb1 extricates the bishop. Carlsen eventually had to retreat all the way to c8 via f5, but this rope-a-dope strategy proved successful, as Anand was lucky to secure the draw.

The idea that Carlsen was playing the Berlin to win rather than simply to draw was confirmed in his next time out with the black pieces:

Anand hasn’t achieved anything with white, but it’s hard to imagine that he’s going to lose this game. His next move allowed doubled e-pawns: 23 Qg4 (23 Qe2 would avoid what happened in the game, but Carlsen could either make a draw by taking on e3 or play 23 … c6 to see if the bishop is a tiny bit better than the knight) 23 … Bxe3 24 fxe3 Qe7 25 Rf1 c5! 26 Kh2 c4! By quickly undermining white’s structure he was eventually able to win a pawn, and then, with a little help from Anand, the game.

The ninth game had the potential to be the best of the match. Carlsen returned to his policy of provoking Anand, and Vishy, eager to stir things up and get back in the match, obliged with a very dangerous looking attack:

Anand was in his element; he played 27 Rf4!, not afraid of 27 … b1=Q+. Now he had to choose which way to block. 28 Bf1 runs into 28 … Qd1! 29 Rh4 Qh5 30 Nxh5 gxh5 31 Rxh5 Bf5 when black has for the moment stopped mate and the position remains very complicated. Looking to improve upon this line, Anand played 28 Nf1? His point was that 28 … Qd1? no longer works: 29 Rh4 Qh5 30 Rxh5 gxh5 31 Ne3 Be6 32 Bxd5! and win whites, as 32 … Bxd5 loses to 33 Nf5! The problem is that Carlsen had the simple refutation 28 … Qe1! and white had to resign in light of 29 Rh4 Qxh4.

You’ll notice that Carlsen had black in all three of the games profiled here; with the exception of game five, another nice endgame grind, Carlsen got very little with white, a problem that would plague him in future matches and generally lower their chess content.

Legacy (2nd Place, 11 points)

The legacy of a match is not determined by the quality of the games, as demonstrated in a chess.com article that (incorrectly) ranked this match higher than many of its more thrilling predecessors. Carlsen is the most important chess figure of the 21st century, and his ascension to the world championship in 2013 was one of the most important moments in recent chess history. Carlsen’s strategy for these matches was revealed here as well: avoid risky middlegames, play non-theoretical openings with white, and try to grind out wins from favorable endgame positions. It wasn’t the most thrilling approach, but he was able to set the tone in this match and the four that followed, effectively forcing each of his opponents to play to his strengths.

#7: Garry Kasparov-Vladimir Kramnik, 2000 (27 points)

Legitimacy (6th Place, 7 points)

What could be better than a match between Kasparov, number one on the rating list and world champion since I was in kindergarten, and Kramnik, third by rating and a constant thorn in Kasparov’s side? In the years before the match, Kramnik had defeated Kasparov’s favorite King’s Indian Defense twice, and won a remarkable game on the black side of the Semi-Slav. Normally such a match would have a very high legitimacy score, but there’s one problem: Kramnik didn’t qualify for the world championship. Shirov did when he beat Kramnik in the semis.

When writing about these matches I’m giving myself freedom to imagine alternatives that would have been more exciting, challenging, historically significant. In this case such an alternative became reality after sponsorship for a Kasparov-Shirov match fell through. The world got a better match6, but the process itself was illegitimate. I’ll split the difference and rank it in the middle of the pack.

Excitement (9th Place, 4 points)

There are a variety of ways to think about how exciting this match was. At the time, it felt pretty exciting that someone was actually beating Kasparov, and the fact that Kramnik’s lead was just a single game for so long increased the feeling that either player could win. No matter how poorly Kasparov was playing, it was hard to shake the feeling that he was going to find a way to survive. We’re talking about a guy with more world championship match experience that any other human being, whereas for Kramnik it was all brand new.

The flip side is that Kasparov didn’t win any games and wasn't all that close to doing so. The match peaked between games two and four: Kramnik won game two, Kasparov gave it his all against the Berlin in game three but was denied by strong defense, and then Kramnik was on the verge of winning game four but couldn’t bring the point home. Like so many of these lower ranked matches, the excitement drained away as Kramnik extended his lead to two games and then played to draw out the match, a strategy that Kasparov was unable to break.

Chess Content (9th Place, 4 points)

This match, like the other two in this article, suffered from too many quick draws. Five of Kasparov’s eight games with the white pieces were remarkably dull, as he made no progress against Kramnik’s Berlin (other than the third game) or the two times he trotted out the English.

To find interesting chess content, we must turn to the games in which Kramnik played white. After rocking Kasparov’s Grunfeld in game two, Kasparov went to his backup weapon against 1 d4, which was, oddly enough, the Queen’s Gambit Accepted:

Kasparov had been getting steadily pushed backwards and decided to seek counterplay and complications: 25 … Rc2 26 Bxa6 Bxa6 27 Rxd7 Rxb2 28 Ra7 Bb5 (to be able to block with Be8 after Ra8+) 29 f5 exf5 30 exf5 Re2! (already an only move) 31 Nfd4 Re1+ (the computer likes 31 … Rxe3 better, but then white wins the pieces immediately: 32 Nxb5 Bxg5 33 fxg6) 32 Kf2 Rf1+ 33 Kg2! Nh4+ 34 Kh3 Rh1+ 35 Kg4 Be8:

You can probably count on your fingers the number of positions that Kasparov reached that were this discoordinated. It didn’t get much better from here, either: 36 Bf2 Ng2 37 Ra8 Rf1 38 Kf3 Nh4+ 39 Ke2 Rh1 (the rook and return return to their sorry outposts on the h-file; now it’s time to go for the kill) 40 Nb5 Bxg5 (what else?) 41 Nc7 and white wins a piece. You might be tempted to say game over at this point, but Kasparov struggled on, giving up everything he had left to simplify the position:

We don’t have space to go into where Kramnik missed the win, but it turns out that this position is drawn. Kasparov erred, playing 58 … Rh1? rather than keeping his rook on the a-file, but Kramnik returned the favor with 59 Kb2? He needed to find 59 Rg8! instead, with the point being the knight cannot be captured. and if 59 … Ra1 then 60 Nd5+! and black has no good king move: 60 … Kxa6? 61 Ra8+ picks up the rook, whereas 60 … Kc5 61 Rg5! and the pawn is still immune.

Without a doubt this was one of the most compelling world championship games of the past 25 years, and although game six was also quite exciting, Kasparov’s energy to fight these kinds of battles waned, and by game ten7 his play was unrecognizable.

Legacy (1st Place, 12 points)

This is an easy one. Not only did Kramnik end Kasparov’s fifteen year reign at the top of the chess world, but in the process he established the Berlin Defense as a drawing weapon, particularly effective against aggressive players such as Kasparov. Guess how many times 1 e4 was played in the 2006, 2008, and 2010 matches combined? Just once, by Anand against Kramnik, in the final game of the match when a draw was as good as a win. I can’t think of another player or opening who has so fundamentally reshaped the chess landscape, for better or for worse.

Anand, ranked second in the world, participated in the other half of the world championship cycle, the knockout tournament won by Ponomariov.

This was the last match that gave the champ tie-odds rather than going to rapid tiebreaks, a fix that would have been better if the tiebreaks happened before the match rather than after it.

A crazy strategy given that Kramnik had draw odds.

Although even the epic games of this match have some of the stink of the draw death of chess on them: Leko’s long victory in game five came from and opening in which Kramnik was content to sacrifice a pawn in order to trade the queenside pawns and survive a four vs. three ending. Without Leko’s impressive technique and a couple Kramnik errors, we would be talking about a much less impressive game.

What do you mean, you don’t have seconds?

Given Kasparov’s huge record against Shirov.

His second loss, which given how things were going, pretty much put the match out of reach.