In the late summer of 2002, the Oakland A’s, despite having lost three of their best players during the offseason, won twenty straight games. This streak and the division title they later won was credited to the clever tinkering of general manager Billy Beane, who sought players with skills (such as high on-base-percentage) that were undervalued by traditional scouts and front offices. Michael Lewis published Moneyball the following year, and his story of the triumph of Beane’s use of analytics over crusty old-school baseball scouts was popular enough to power a movie starring Brad Pitt in 2011.

Hooray for math, you most unlikely protagonist and hero! But in 2025 you don’t have to look far to find articles about how the analytics revolution has ruined baseball or basketball. By perfecting these sports, the argument goes, we’ve destroyed what makes them exciting. As Derek Thompson put it, musing the pages of The Atlantic about his sudden decrease in interest, “I think what happened is that baseball was colonized by math and got solved like an equation.” I had the same experience, and I haven’t watched baseball seriously in about a decade.

I’m worried that something similar is happening (or perhaps has already happened) to modern chess.

To enjoy being a fan, to sit in rapt attention in a crowded arena or at an elite chess tournament, requires that the competitive event you are watching is to some extent unpredictable. While it can be illuminating or educational to watch an event in which you already know the final result, it is never tense or dramatic or thrilling after the fact. The 2024 World Chess Championship was exciting in the moment because the players could produce blunders or brilliancies at any time; that it concluded with a blunder increased the drama and emotional pull of the final game. Similarly, my enjoyment of watching a basketball game is heightened because I don’t know if Steph Curry is going to hit another three or whether Heliot Ramos is going to hit a home run or strike out.

Directly related to the question of unpredictability and excitement is the idea of the metagame: that is, the set of possible strategies that a team or player will use in order to increase their chances of winning. When more types of strategies are in play, the metagame is larger and the contest is less predictable and more exciting. When the metagame shrinks to just a few possible strategies, the direction events will take is more predictable, even if the outcome remains uncertain. The analytics revolution is a direct assault upon the metagame, as it involves finding the very best strategy or set of strategies and repeating them, ad nauseam, to maximize the chances of winning. In any competitive environment with little differentiation between the skill level of the best players or teams, to not aim for the strategy with the best chance of success is idiotic. And so, more and more baseball teams began trying to take walks and hit home runs, and more and more basketball teams began running plays to open up a player to take a corner three, and more and more chess players began playing the Giuoco Pianissimo.

Here’s an interesting fact: in the 2025 Wijk aan Zee tournament, white played 1 e4 in 45 games in the masters section. Black responded with the Sicilian Defense nine times, with either the French or Caro-Kann seven times, and with 1 … e5 a remarkable 29 times. 23 of these games were drawn, a rate of futility that could be interpreted as either a bit of an outlier or a harbinger of things to come. In any case, the preference of the top players for double-king pawn openings is clear1: in 2024 23 games began 1 e4 e5, in 2023 there were 30 (compared to six and seven Sicilians, respectively). It wasn’t always like this. In the same tournament2 in 2000, the Sicilian occurred seventeen times, double king-pawn nine times, and either French or Caro eleven times.

The Moneyball story is about leveraging small advantages to gain a leg up on your competitors. Bobby Fischer is one of chess’s original Moneyball figures, looking back to forgotten ideas from the 19th century to spring on unsuspecting opponents. Kasparov is another, working more deeply on opening theory than any of his competitors were willing or able to do in the last years of the pre-computer era. Not all of his innovations were sound, but they were extremely difficult to meet over the board.

Vladimir Kramnik’s approach to the 2000 World Championship match, coming just two years before the Moneyball A’s, was in some ways the most brilliant and most damaging innovation; it has certainly had a powerful impact on modern chess. He demonstrated at the highest level that it was possible to aim for a slightly inferior position as long as you knew how to defend it accurately, and his Berlin Defense killed 1 e4 as an attacking weapon for some time. It did not appear in the 2006, 2008, or 2010 championship matches, save for a final game that Anand was happy to draw in 2010. And despite the remaining loyalists to the Sicilian or those looking to the surprise value of the French, 1 e4 e5 has cemented itself as the central tabiya of modern chess.

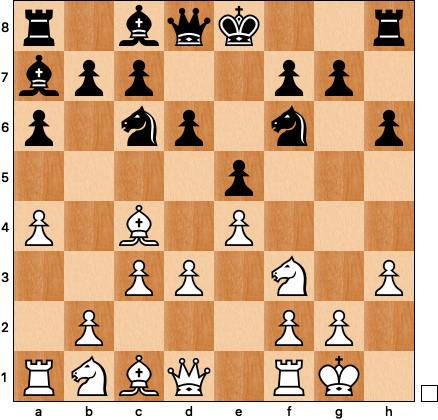

Let’s take a moment to consider the problem with chess converging towards a million Giuoco Pianissimos. The chart above splits chess openings into four quadrants, although the vast majority of elite grandmaster games fall into the top two: the world’s best players are nothing if not trendy. During the Fischer and Kasparov eras many battles were fought deep in the trenches of theory, in the King’s Indian, the Grünfeld, the Najdorf, and the Dragon. Computer theory has solved many of the sharpest tactical openings conclusively. There is no point in venturing down a variation in which your opponent has already memorized the drawing formula.

This has pushed the metagame of chess openings and strategy away from the most theoretical and tactical variations towards lines that are more systems-based3. Instead of the mutual chances of attack and counterattack of the open Sicilian, we’re watching players try to pick the right moment to maneuver a knight to f5 or break with d3-d4. I guess this could be exciting in some contexts, except that so many double king-pawn games end up as draws, a cold shower for fan engagement, the chess equivalent of another strikeout by a baseball player trying to hit a three-run homer or yet another corner three, the most theoretically efficient shot in basketball, off-iron.

Thus modern chess players are caught in a nasty paradox. In order to generate winning chances, they have to avoid the sharpest variations that are more or less played out, but in doing so they struggle to generate chances from symmetrical positions that lack tension. Fans struggle to enjoy the positions that arise, which tend to be extremely subtle and likely to end in a draw anyway4. The metagame shrinks from a vibrant and compelling ecosystem of openings and strategic ideas to one that feels stale and predictable. We’re living in the upper-right quadrant these days, and it’s not particularly thrilling.

Fortunately, there’s a solution to this problem, and it’s called … Freestyle! Metagame shrinkage getting you down? The Freestyle metagame is modern opening theory times 960. There are no Berlins here, no Giuoco Pianissimos, just chaos and tactics and wildly entertaining games, the kind of chess that, as Carlsen put it, is all about the “childish joy of just playing chess rather than being worried about openings, rating points, and all of those things that are important but don’t necessarily equate joy.”

If this is true, why is following Freestyle as a fan such a drag?

As a fan of chess, I follow ongoing tournaments in a variety of ways. At my most engaged, I do a deep dive analyzing and annotating a specific game, typically with the goal of writing something about it on this site. At other times I watch the games live, following along with the grandmaster analysis, considering what I would play in specific situations. But most frequently I review the games of the round after they’ve concluded, a speed-run approach in which I try to get the gist of each game without devoting too much time to any one position or problem.

With traditional chess this approach works just fine. I know something about just about every opening system, so I know what kinds of plans are possible and what to expect. I can quickly form a narrative that helps me understand remember key parts of the game: for example, “Oh, this was a Sicilian in which black pushed a6-b5, but white broke up the queenside pawns and eventually won the pawn on a6.” It’s a little simplistic, but it allows me to look at a lot of games quickly and think about what’s happening in the tournament overall: who’s in good form, what sorts of new ideas are out there, etc.

In Freestyle that quick method of going through games is a complete disaster. I either slow way down and do some deeper thinking (as I did and then wrote about last week), or I speed through in utter bafflement. My pre-existing knowledge about chess often leads to confusion, as my assumptions about tactics and coordination are often incorrect. There’s no way to casually go through a Freestyle game and understand it: Freestyle requires the sort of cognitive commitment that I wish I had more time for, but frankly do not. It’s pretty much the opposite of the reaction Carlsen has as a player. Despite the weird variety of positions and plans, I find the fan experience of Freestyle somewhat less freeing and joyful.

Ultimately, this irritation with chaos is an important thing to understand about the fan experience. Part of unpredictability is knowing something about what to expect: sports and games are most thrilling when our expectations are upset, that something more brilliant and more astonishing than we anticipated is possible. When there’s a runner on second base and two outs I might be surprised when he steals third and then scores on a wild pitch rather than being driven in conventionally by a single to the outfield; when black is attacking on the kingside I might be shocked by the inclusion of a move like b7-b5 rather than what seems like the natural continuation of the attack. That’s the fun: I think I know something about what’s going to happen, but ultimately the elite players know better5.

What do other sports do when the metagame gets out of whack? They change the rules, but not so much that the sport is unrecognizable. When the shift made baseball less fun, baseball outlawed it. When in the past pitchers were striking out too many hitters, baseball lowered the pitching mound. Basketball increased the size of the key to limit the dominance of certain players around the hoop, and it seems likely that the three point line will be moved back sometime in the next decade. Not all of these solutions are perfect, but they show a generally understanding that finding the right metagame balance is the key to fan enjoyment.

What should chess do? Freestyle is the equivalent of replacing the traditional baseball with some other round object at the start of each game. Today we’re hitting a tennis ball, tomorrow a beach ball, the next day an … apple? I don’t mind it as an occasional exhibition of Freestyle chess, but I’m not yet convinced that we need an entire chess tour devoted to it. I’m beginning to think that we’d be better off pulling openings out of a hat to force players back into the richness that is classical chess, with one interesting twist: the players get to bid clock time to decide who will play white from the determined starting position. We would get to see new wrinkles in less trendy variations, more complex fights, and all sorts of gamesmanship around how much time to bid. It’s not as sexy as Freestyle, so I’m not expecting the next rich guy with a passion for chess to fund it, but it’s almost certainly worth a try.

The closed openings are a little more varied, but there is a strong tendency towards the Queen’s Gambit Declined and the Slav ahead of old favorites like the King’s Indian or Grünfeld.

Back when it was named Corus.

With the caveat that the top players are building a lot of theory even in these types of openings; consider the twenty or so moves of theory that Ding Liren blitzed out when he played the London System against Gukesh last winter.

Carlsen is in some ways the perfect champion for this era given that he is so good at extracting chances for these positions. That he is also one of the loudest voices about how stifling modern chess has become is rather troubling.

Which is one of the problems with the eval bar and computer evaluations during the broadcast of top tournaments: it’s not nearly as fun when the computer is telling you what to think.

This is such a sharp diagnosis of modern chess’s paradox: the better we get at “solving” it, the more it risks becoming sterile for spectators. The Moneyball analogy fits disturbingly well, and your take on Freestyle being cognitively demanding rather than liberating as a viewer really landed. It’s clear we need innovation, but also a better way to reintroduce creative friction into classical chess. The idea of randomized openings with time bidding is compelling, it feels like a path back to surprise without sacrificing structure.

Really great piece — I'm not sure I've seen as concise and direct an explanation of the challenges facing modern chess.

One thing that I think is also fascinating to consider is the difference in how most people who are passionate with chess engage with the game versus the way that people do with other sports. I would imagine it's safe to say that the vast majority of (adult) fans of others sports a) play the sport casually, or not at all; and b) predominantly watch the elite practitioners versus lower-level players. Chess is the exact opposite: most fans a) play more than they spectate and b) engage with non top-tier players like Levy and Eric Rosen more than they do non-streaming pros. (And then when they do engage with someone like Hikaru, they're watching him stream, which is basically like watching Steph Curry play pick-up).

For those reasons, I've always thought that quicker time controls held the most promise for getting fans to engage with top-tier chess: at least you can comprehend the game, but there isn't as much room for the level of precision that allows these endless draws. On top of that, it's how most fans engage with the sport anyway, whether through their own online games or by watching streamers.

But I honestly have no idea if that's the solution — and I am definitely in the camp of person who prefers to play long games, so I understand why the players are resistant!